Who are the pink pussyhats helping?

The problem with their pinkness

On Jan. 21, about 300,000 people stood in solidarity at the annual Women’s March in Chicago, exceeding last year’s attendance by about 50,000. What was different about this year’s march is its focus on a “march to the polls,” encouraging women to vote and run for office in November. What was the same is the lack of intersectional feminism, aided by the appearance of the controversial “pink pussyhats.”

The hats were created by artist Jayna Zweiman and screenwriter Krista Suh from the Pussyhat Project on Nov. 23, 2016 to be worn at the 2017 march. Their mission statement declares that they are “dedicated to advancing women’s rights and human rights through the arts, education and respectful dialogue,” according to their website.

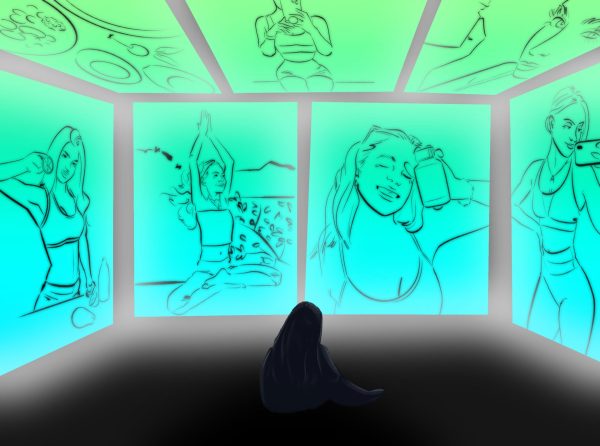

(John Locher | AP)This may not be the case, as many have condemned the hats, saying their color and representation of cat ears emphasize dated stereotypes of femininity. From the bright pink color, which some women feel reiterates gender stereotypes, to the literal word “pussy” that excludes those of trans and non-binary genders, these hats call to white women whose feminism includes Tina Fey’s “Bossypants” but not Roxane Gay’s “Bad Feminist.”

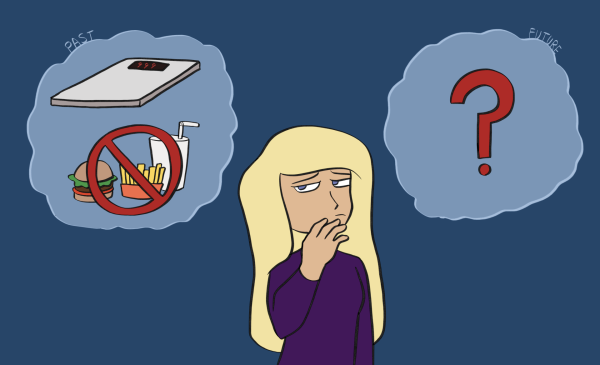

These hats fail to reach a large majority of their target audience: everyone that isn’t white and everyone that doesn’t have a vagina. While they purport to reclaim the color pink as a symbol of female solidarity, the use of the color simply reaffirms the marchers’ softness, as well as an outdated form of pure and girlish femininity. Their mission to mobilize a “feminine sea of power” is admirable, but it ignores those who are attempting to distance the idea of “pink purity” form the feminist movement. Femininity means persistence and solidarity, not pre-existing notions of what is “female,” or those put forth by past generations.

“I couldn’t move without being bombarded by white women in those hats. They don’t know (the hats are) problematic and that adds so much to the conversation of intersectionality.”

— Andy Billingsley

A sea of pink is a solidifying gesture, yet the color could have easily been changed to purple, the color most identified with LGBTQ+ rights and royalty which would further indicate the “march to the polls” goal to get women into positions of power.

“I care more about mobilizing people to the polls than wearing one hat one day of the year,” said Phoebe Hoppes, founder and president of the Women’s March in Michigan.

The association of women and the color pink is nothing we haven’t heard before; in fact, we’ve been taught women and pink go together for decades. The origin of pink’s association with femininity came about back in the mid-20th century for marketability purposes. World War II helped solidify the social construct with the emergence of mass marketing using images of little girls, their dolls and toys all donning the image of pure, pink femininity.

As the stereotypes of women as mothers, chefs, homemakers and housemaids declined, the association with women and pink should have as well.

The hats don’t allow for the social growth of intersectional feminism. The hats do allow older, white women to feel as if they are helping the cause to mobilize women to the polls, in a hypocritical and tone-deaf daze. Showing support through actions that change government policy is still the most effective way to battle social inequalities.