I am not a bot

The New York Times released a story that exposed an American company that sells and distributes fake Twitter followers. (Dreamstime/TNS)

On Jan. 27, the New York Times broke a story entitled “The Follower Factory” that exposed the American company Devumi for selling and distributing fake Twitter followers to users. Some of their customers include public figures like the football commentator Ray Lewis, actor John Leguizamo and the Chicago Sun-Times film critic Richard Roeper, who was suspended amid the controversy.

Social media bots have been a concealed and lucrative business for years. We’ve known they exist, but we’ve been confused about the legality of them. Twitter’s stance on their mass amount of bots is complex because bots are complexities in nature. Proving who or what company bought the bot and programmed it to follow a certain account is difficult without either party coming forward and admitting it, and Twitter’s policy does not require accounts to represent a real person like other social media sites such as Facebook do.

The problem with the fake bots is the ethics surrounding them. Many of them, as NYT points out, are almost exact copies of real people’s accounts. This is technically identity theft because of how authentic some of the accounts look. These accounts have the potential to be defaming if their tweets contain explicit or controversial content. A research team from The Atlantic at Oxford University found that the 2016 presidential election was influenced by bots like these that were programmed to resemble and tweet like Trump or Clinton supporters. Tweets spewing conspiracy theories about the candidates circulate the website, influencing the public’s perceptions though many of the theories had no credibility.

It’s usually easy to tell when you’re interacting with a bot, as there are a few signs. The article splits them into three categories: a “scheduled bot” that tweets things at a certain time, a “watcher bot” that monitors other accounts and tweets out changes and an “amplification bot” that follows, tweets and favorites like a real account. Behind this account is far from a real person.

Devumi sells amplification bots because of public figures like Roeper profit off their follower count. “The more people influencers reach, the more money they make,” says the article as the bottom line. Paying a small amount, literally a penny per follower, to profit later in your career seems like a worthwhile payoff.

“I guess with some people it’s worth it, but it is so frivolous,” said Maverick Cole, a 21-year-old marketing major. “Trying so hard just to look more professional even though people can tell your followers are fake. Some people, there’s just no way they have that many followers, given their like to follower ratio. It’s creepy and just sad to think that all those followers are just fake people pretending like real people.”

In reality, a fake bot, consisting of no pictures or information about real people, are harmless if their function is to increase a person’s follower count. It isn’t ethical by any means, but does it hurt anyone? The careers of public figures who buy them, maybe. In Roeper’s case, his film column will continue as long as he does not write any general interest news stories and that he makes a new Twitter account.

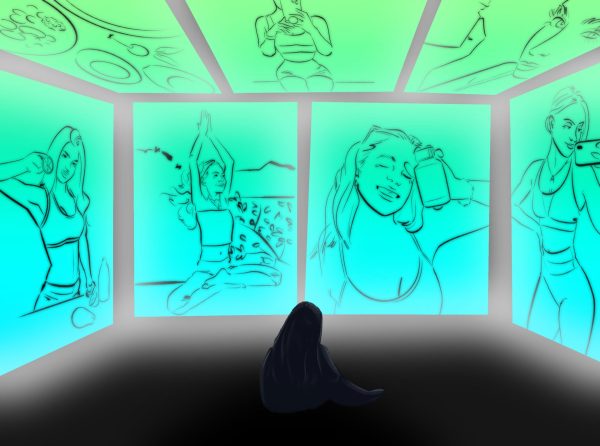

In the age of social media, these bots represent the deeper psychological need for online validation that translates into personal validation. Social status can be increased on the same beat as follower count. Seeing a high follower count instantly increases someone’s credibility, no matter their field. This can be very intimidating, especially if the person is a young adult with no professional credit.

With new and overbearing way to get social status through social media sites, seeing others success that consists of just posting online becomes confusing. One person can gain 20,000 followers for taking aesthetically pleasing and professional model-equse photos, while another doing that same thing can be stuck in a three-month lull of 200 followers. The difference is that one has bought their following, and one has not. Social status now equates to the online following someone has.

Those normal people who buy their followers, not public figures looking for a higher payout, look for the confidence they might have lost in real life online. Their ego shines brighter the more followers they have. Social media influencers are notorious for this: many of them when reviewing food expect the bill to be paid for by the restaurant in exchange for a shout out, claiming their influence should cover the bill.

It’s easy to believe the influence of someone who has thousands of followers, but the NYT exposé adds a layer to the conversation. Like paying for an expensive suit to enhance a business person’s brand, buying more followers provide influencers with a better image. After the story broke though, influencers might begin to deeply reflect on their personal growth and not their follower growth.