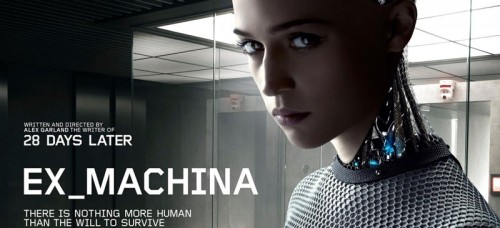

Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), a programmer at the world’s largest Internet company, wins a lottery to spend a week with its CEO Nathan (Oscar Issac). When Caleb arrives, he soon finds that he must participate in an experiment with Nathan’s latest creation, Ava (Alicia Vikander) — the world’s first artificial intelligence, shaped in the form of a young woman.

So what inspired you to write “Ex Machina?”

It probably started when I was a kid, like 12 or 13 years old. I’m 44 now, and my life has kind of kept pace with the develop ment of home computers and video games. When I was about 12 or 13, I got a home computer and you could kind of program it in a very kind of basic language, called Basic in fact. And one of the things you do is set up very simple Q&A programs, like you could make the computer say, “hello” and then you’d say, “hello.” You could ask it how it’s doing and program it to respond saying, “I’m fine.”

You get this sense, this electric sense that the machine is alive. Of course it actually isn’t, it’s not alive in anyway, shape or form. But the feeling it gave, stayed with me. It was like you wished it were alive.

So I stayed interested in A.I. and years later a good friend of mine got really into neuroscience — that was his area really — and he came part of this school of thought that machines can never become self aware. And I used to argue with him about it, because I thought they could. I eventually came across a particular book that really helped make the argument that I believed in; it’s a book by Murray Shanahan, a British professor of cognitive robotics. And the idea of this film came from reading that book.

While you were writing the film did you know you were going to direct?

No, not really because at the point of writing any of these films, I never really think of any of that stuff. It’s just a blueprint for a film, and what you’re really trying to do is persuade people to make your film. And that begins with producers, who are basically the other part of the key relationship with writers.

So I wrote it thinking I like the idea and we could get something off the ground, and then I presented it. It’s sort of like an argument, like trying to win a legal case or business case. You say “let’s do this thing, we can make it with this amount of money, here’s the idea, we can cast it.”

And then the directing thing, it wasn’t like a big deal. I’ve been on set on all my previous films I’ve worked on. I’ve worked with the same group of people for a number of films, and I worked with that same group on this film, only difference being I was the one directed this time.

Was directing a big shift for you given this is your first time?

Honestly, not really. Not at all. There’s too much noise in the word “director,” it’s a load of BS. I mean making a film, is essentially a team process. A film’s hard to make, and a lot can go wrong for sure, but I believe it’s a team job. I mean there’s a reason for the number of names in the credits at the end of a film.

I’m not saying there’s no such thing as an auteur. You can name some off the top your head, like Woody Allen is an auteur of course, but that’s his way of working. It’s not mine. This wasn’t a large film, it was quite small so I had a good team to work with, one that I’ve worked with before.

With such a small cast, was there anything in particular that you looked for in your actors?

There was actually, one thing. The group of actors we chose is without a doubt a talented bunch. But one thing I learned from working in this business, is that being an actor can be easy to fake. We can all think of bad actors working today, but the point is they’re still getting work. And I think that’s because of their charisma. You can be a bad actor but you can fill the screen with your bright charisma and people will still come see you.

On the other hand, when there’s good acting on the screen, anyone can see it. There’s no denying an actor with a great amount of talent, and that’s what I looked for in these three. I didn’t want these charismatic characters on the screen; I mean Ava is a robot, so it’d be strange for Alicia to have a huge amount of charisma. I wanted believable, good acting, and that’s what they delivered.

Speaking of Ava, the fact that she’s a woman says a lot and raises a number of questions both socially and philosophically. In your design of her, do you think she was a woman just in her outer skeleton form, or in her actual A.I. mind?

Well that’s exactly the question, isn’t it? In all my films, I like to ask these types of questions in order to get the audience to think, from the gender of the robot to the Turing test itself. I mean one can say that if Ava was created and put into a male’s body, would her way of thinking change? It’s something I’m not going to answer directly of course, but I want the audience certainly to question it. I mean, is Ava a woman because of her brain or because of her body? I want the audience to tell me.