Since mid-July, the season for attack ads was in full swing, with both political parties’ candidates doling out blows. As constant advertising bombardment commenced, bolstering odd facts and heinous quotes, little is seen or mentioned of the money behind the ads blaring on TV screens as candidates and their supporters fight for the vote.

These ads, of course, are nothing new. No campaign in the modern era has gone without them, but the amount of money being funneled into their creation has surpassed historical records set by the 2012 presidential election. The Illinois governor’s race between incumbent Pat Quinn and Republican opponent Bruce Rauner has only continued the trend.

The Chicago Sun-Times reported a 335 percent increase in campaign spending between the March 18 primary and the end of June for the governor’s race, according to an article by NBC from August.

During this period, the candidates spent about $8 million, far more than the collective $1.8 million Quinn and 2010 gubernatorial candidate Bill Brady spent in their race. The flow of money has continued as the race has grown more hostile, and the polling figures display a neck-to-neck race.

Buying this media time is costly — especially in the race for governor, which has been deemed a “dead heat” by news outlets in the region — but for the voter sitting on the couch the ads and other measures used by candidates may seem like overkill.

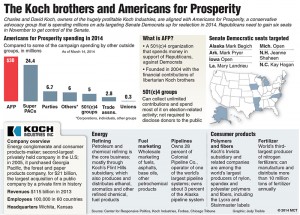

“Some people argue that money in campaigns is necessary because media time is costly. Candidates need to attract those with money to conduct a viable campaign,” Catherine May, a DePaul political science professor, said. “Money buys access and influence, and this can correlate with policies which benefit those money-giving interests. It gives (those interests) that are well-organized and well-financed a distinct advantage in getting their interests heard over the unorganized majority who have limited resources.”

The role of money in politics moves past just general elections, according to May, but the connection between elections and the prominence of certain groups, such as the NRA — or, to a lesser extent, Planned Parenthood — is also problematic; groups such as the NRA, who are able to raise money and donate freely, get a much larger seat at the table of politics.

Other possibilities for contributions come from Political Action Committees, or PACs, set up for candidates that allow the average worker with more than a little cash to spare to donate to campaigns; the limit on these contributions was overturned in April in McCutcheon v. FEC. Taxpayers for Quinn recently received more than $1 million in contributions of various sizes, but this is merely one of the many contributions made to the democrat’s campaign.

“Interest groups have too much economic power, which leads to them having political power,” William Sampson, head of DePaul’s Public Policy Department, said. “If we restored politics to the public and enacted public financing of elections, we could cut down on some of these problems and drive down the costs of elections.”

In other countries, money is not exchanged for media time, and perhaps it’s about time the United States followed suit. However, no changes are likely to be seen in the political process, especially for how campaigns are conducted. What happened to the days of bashing your candidate on the radio or in an open house? Money, many analysts would say.

Political efficacy in our country is underwhelming, perhaps a direct result of the massive role money plays in the system and the knowledge or perception that the people don’t have a voice. However, that’s largely an incorrect assumption. Even if people identify with opposing parties, voting and letting their voices be heard is highly important if change is truly desired.

“This is a dumb public,” Sampson said. “(It) has to wake up and stop voting against its own interests and remove the reactionary figures we have from power (to see change).”

May largely agreed. “Reform is possible, but the public and congress need to realize that the integrity and legitimacy of our democracy rests on giving real power to majority interests which any reasonable understanding of democracy must include,” May said.