Recent downturns in the news industry have perpetuated the use of grim language

If you know a bit about journalism, perhaps you’re familiar with the old saying, “If it bleeds, it leads.” For those who are out of the loop, this saying refers to the idea that, basically, bad news—death, catastrophe, misfortune— commands the attention of readers more than good news.

If you know a bit about journalism, perhaps you’re familiar with the old saying, “If it bleeds, it leads.” For those who are out of the loop, this saying refers to the idea that, basically, bad news—death, catastrophe, misfortune— commands the attention of readers more than good news.

If that sounds at all inaccurate, just look at the top stories of any circulated publication. This year, headlines have irrefutably been dominated by violent crime, drug abuse, political scandal and sexual assault. I am not positing that such issues are undeserving of the coverage they currently receive. I am, however, posing a difficult question: Why do these topics comprise the overwhelming majority of news material?

Could it be because we’re primal beings who become excited by acts of aggression? Or because the world is overwhelmed with hostility and malevolence? Both are undoubtedly true to some extent, but Harvard psychology professor and bestselling author Steven Pinker makes a more comprehensive case on the subject in his most recent book, “Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress.”

In his book, Pinker refers to a study conducted in 2011 by Dr. Kalev Leetaru, a renowned entrepreneur and data scientist. In the study, Leetaru applied a technique called “sentiment mining” to every article published in The New York Times between 1945 and 2005, and to an archive of translated articles and broadcasts from 130 countries between 1979 and 2010. Sentiment mining assesses the emotional tone of a text by recording the number and contexts of words with positive and negative connotations, such as good, bad, horrible and excellent. In 2016, Leetaru wrote an article for Forbes magazine containing the results of the study.

“Global news media has become steadily more negative over the last quarter century,” Leetaru writes. “The timeline below shows the standardized (Z-score) average monthly tone of global media collected by BBC Monitoring from January 1979 to July 2010, showing a nearly linear descent towards ever-greater negativity year over year.”

The results of the study are puzzling, especially when one considers the wealth of underreported good news that has come to light over the past few years. For instance, the Pew Research Center reported that property crime and violent crime in the U.S. have been falling steadily since the early 1990s; the World Bank reported that the global rate of extreme poverty dropped from 35.9 percent (1.9 billion people) in 1990 to 10 percent (736 million people) in 2015 (the most significant decline in recorded human history); the UN’s annual human development index found that from 1990 to 2017 the average life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa rose from 49.7 years to 60.7 years due to improved nutrition and reduced child mortality rates; and the Lancet, a renowned medical journal funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, published a study revealing that obesity now poses a greater threat to humanity than starvation.

“As we care about more of humanity, we’re apt to mistake the harms around us for signs of how low the world sunk rather than how high our standards have risen,” Pinker writes. Language plays a fundamental role in how the news shapes our perception of the world. If news coverage is becoming increasingly rife with morose language, then it’s perfectly understandable why more encouraging findings seem to go largely unnoticed.

“It is critically important to recognize that the world’s news media is not an unbiased and complete record of society, nor does it provide a uniform and standardized view across nations,” Leetaru continues. “The presses of each city around the world reflect and internalize global and local events and narratives for their respective audiences … The tone of news coverage (and social media) does not necessarily reflect the emotional state of those within an area, nor is computerized sentiment mining without its limitations.”

DePaul senior Ollie Kahveci thinks that advancements in technology have played a vital role in promoting sensationalized news coverage.

“Technology has increased the amount of media that we’re exposed to to the point that we’re becoming numb to it,” Kahveci said. “In order to get the same stimulation the stories have to be more disturbing and violent than ever before.”

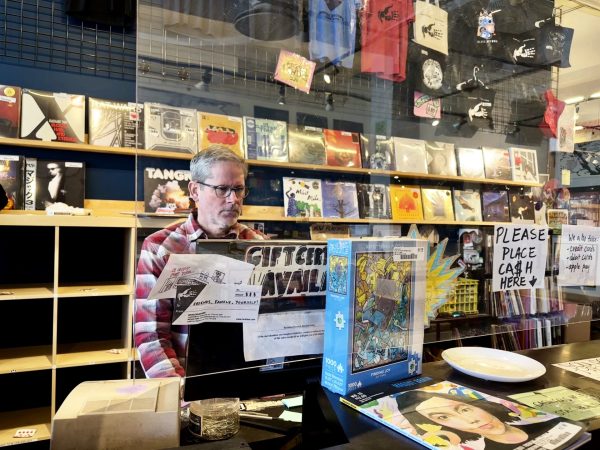

Findings from the Pew Research Center show that while the number of people who get news from online sources, social media, apps and podcasts is rising steadily, newspaper circulation and viewership of cable news continue to plummet. Moreover, advertising and circulation revenue of the newspaper industry has dropped by about 66 percent over the last 12 years.

If an industry is in danger, it must necessitate itself to consumers in order to stay afloat. But for the news industry, earning a profit through online readership is a far more complex process than selling a single, tangible product like a newspaper. This means that catching the attention of readers and viewers by any means necessary becomes the top priority. However, this is not a sustainable tactic in the long-run. Sooner or later, the consumers will realize the game that is being played.

As the statistics clearly show, more and more people are turning away from traditional mainstream news outlets and toward more alternative, independent and unconventional sources. If the news industry wants to survive, it must ditch its futile, opportunistic strategies and figure out a way to rebirth itself during an age when online content has become the new normal.

Graphics by Annalisa Baranowski | The DePaulia