History of Notre Dame Cathedral shows gravity of what was lost

Courtesy of Nitot / Wikimedia Commons

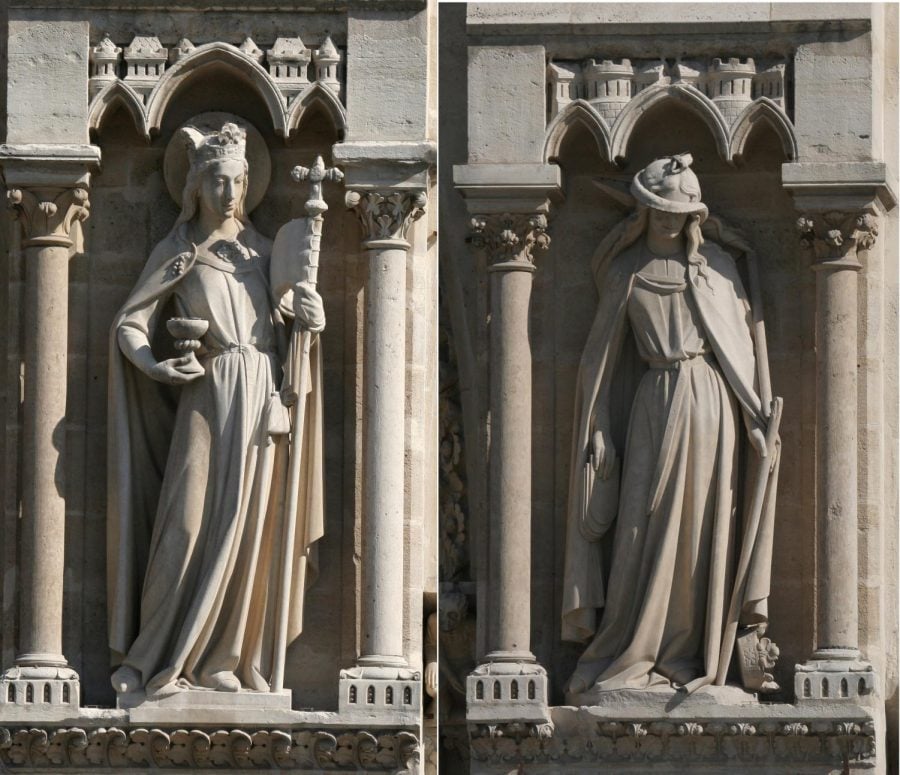

Notre-Dame de Paris. 3rd statue (from left to right) on the West Entrance: the Synagogue.

At 6:30 p.m. on Monday April 15th, the busy streets of Paris bustled around an astronomical cloud of smoke emitting from the center of the city. In awe, passersby gazed at the plumes of flame emanating from the roof of one of the most sacred and holy sites of France. The Notre Dame Cathedral — a centuries-old piece of heritage, pilgrimage and daily life — was ablaze. Days later, it became clear that while the Gothic cathedral’s towers remained and many of its religious relics had been preserved, a full recovery was a long way off.

“We would go every Sunday afternoon to hear the organs being played,” said Dr. Karen Scott, a history and Catholic studies professor at DePaul who has taught in Paris with DePaul’s Study Abroad program.

According to Scott, the cathedral was an important part of the city going back to the pre-Roman era. Fortified in the first century B.C.E., it was constructed on its own little island in the Seine River starting in 1163, at the command of King Louis VII. It went through many phases thereafter, with one of the most infamous being its Enlightenment-era iteration as a “Temple of Reason,” so named by the French Revolutionaries who seized it in 1793; it was quickly refurbished and returned to the Catholic Church after French commander — and later emperor — Napoleon Bonaparte’s takeover.

While today a large percentage of French people describe themselves as irreligious, Scott said Notre Dame has nonetheless become “a symbol of the city.” The French government, in fact, owns the cathedral — it merely lends it to the Catholic Church.

“The French thought it symbolized power, some sort of sanctuary,” said DePaul student Camila Cortez, who is studying for a minor in museum studies and studied abroad in France last year. On her trip, she also learned about Notre Dame’s history as a site of religious pilgrimage, as well as the numerous supposedly-divine relics housed there.

Tanya Stabler, a medievalist specializing in 13th-and 14th-century Paris, explained that the artifacts are of enormous religious importance.

“When I thought the Crown of Thorns and Tunic of Saint Louis were gone, I cried,” she said.

Almost immediately, international media seized on the story of Paris fire brigade chaplain Jean Marc-Fournier, who raced into the burning cathedral to save the Crown of Thorns; he and over 600 other firefighters were honored during ceremonies on the Thursday following the blaze. While the fire destroyed the roof, the cathedral’s famed Great Organ, its rose windows, a number of crosses and other artworks inside were saved.

Stabler said the mourning over the damage to Notre Dame has transcended religious boundaries.

“Paris is a multicultural city and even people who aren’t Catholic recognize this building as a symbol of Paris,” she said.

Despite this, Stabler said it’s important to acknowledge some of the lesser-known history of the cathedral, which does include anti-Semitic motifs put in place during the Middle Ages, such as statues Ecclesia and Synagoga.

“I know in some churches including Notre Dame, there would be some representation of the synagogue as being inferior to the ecclesias,” Stabler said, referring to the area of the church where the congregation gathers.

In the front of Notre Dame there is a derived synagogue with a snake in its blindfold to represent how “misguided” the Jewish population was. It was during an age where the French kings were casting out Jews and strengthening their anti-Semitism.

While some are optimistic Notre Dame will recover will the help of architectural study and technology like modern 3D imaging, there is pessimism as well. Notre Dame was already undergoing renovation work before the fire occurred, and in the aftermath as some of the world’s richest individuals like François-Henri Pirault and Bernard Arnault, raised millions of dollars for the rebuilding effort, there were cries of unfairness and a tone deafness to economic inequality. Some pointed to sites such as Palmyra, Bamiyan Buddha statues and others that were destroyed because of catastrophe or human war but which did not receive as much funding or attention from the international community.

Despite everything, though, the Notre Dame Cathedral touches a chord for many who have studied it, visited it or prayed within its walls.

“One year, I went to the Vigil of Easter,” Scott reminisced. “The whole church was pitch black, and the service started and it was an eerie experience. The building slowly came to life with everyone carrying a candle, with the light of hope overcoming the darkness.”