50 years of Joan Didion

The bored, sad white woman trope is wearing thin.

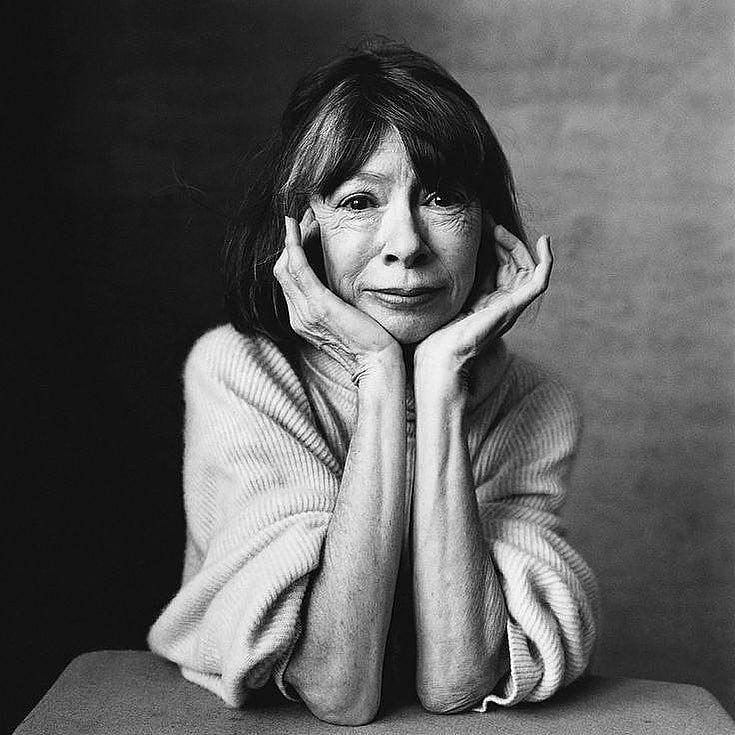

Joan Didion, the author of ‘Play It as It Lays,’ poses for a picture.

I remember the first time I read Joan Didion’s “Play It as It Lays” vividly.

I was 16, bored with suburbia and sold on a grossly overplayed illusion born out of extensive Tumblr use that I would move to California (I moved to Chicago), become aloof (I’ve never been aloof) and write sad poetry (I don’t write poetry).

For that, Didion was an embarrassingly perfect fit – while Didion and I are nothing alike, she was still relatable in the grand scheme of white woman sadness. And Didion is cool, detached and at the forefront of counterculture seemingly without trying.

“Play It as It Lays” mirrors that.

The novel depicts the life of 31-year-old Maria, a former quasi-successful actress confined to a psychiatric hospital in California.

Through fragmented and nonlinear chapters, the reader learns about Maria’s divorce with a former film-maker, her disabled and estranged 4-year-old daughter Kate and an abortion that she never really wanted to have. Her life as a wife and mother appears idyllic in her expensive Los Angeles home, but she rejects traditional roles in a very second wave feminist fashion and instead is consumed by constant existential dread and self destructive behavior.

Add Didion’s piercing, bleak prose and you have yourself a novel that is equally hypnotic and haunting.

“There was silence,” Didion writes. “Something real was happening: this was, as it were, her life. If she could keep that in mind she would be able to play it through, do the right thing, whatever that meant.”

Didion captures the chaos and privilege of Hollywood in the late ‘60s. Maria navigates alienation amongst Hollywood filmmakers and actors, compulsive sexual endeavors and her own roles in the same detached fashion that makes Didion so revered. After the abortion, facilitated by her ex-husband who was not the father, Maria unravels. She can’t see Kate, no one is hiring her and she can’t stop drinking.

The book ends (spoiler alert) with Maria being institutionalized after watching her friend BZ take his own life.

Didion herself is a legacy for her essays that brought dizzying California subcultures to the forefront of American culture. Much of what we know about the West Coast in the‘ 60s and ‘70s comes from Didion. Her political and cultural work spans from the 1960s to 2010s and from California to El Salvador to New York City.

One of her most influential characteristics is her ability to transform personal essays into works of serious extra-personal weight. Her book of essays “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” published in 1968, evaluate John Wayne, detail unhinged San Francisco counterculture and analyze morality in a Death Valley hotel. Throughout it, she lets emotion exist alongside truth, and her commitment to objectivity only goes as far to not place blame.

I still revere Didion for writing that knocks me off my feet. But in the 50 years since “Play It as It Lays” was published, the trope of the bored, sad white woman is wearing thin.

Sure, Didion is excellent, but she spoke to me because I, too, am a bored white woman who is sometimes sad. And because of this, I have access to an immense amount of literature catered directly to me (see: Sylvia Plath, Joyce Carol Oates, Sally Rooney).

Not everyone has the same luxury.

In her memoir “Negroland,” Margo Jefferson writes about growing up black in the 1950s and ‘60s where she was “denied the privilege of freely yielding to depression, of flaunting neurosis as a mark of social and psychic complexity. A privilege that was glorified in the literature of white female suffering.”

Didion represents something that is not accessible.

While she does give female sadness space at a time when that wasn’t altogether common, she also represents a specific type of emotional expression that is only reserved for some. This is noteworthy in a time when intersectionality is, and should be, a priority.

Not to mention the life of the rich, stylish artist who is terribly intelligent and terribly bored with her terribly seamless life is expensive and elitist.

In “Play It as It Lays,” Maria designates hours to drive on Los Angeles freeways, frequenting motels and bars, and can afford an illegal abortion. To be fair, this is the expression of a valid crisis of mental health. But having the privilege to not worry about finances and being given the space to mull for hours is not something that everyone can afford to do.

Maria’s patterned draw to turbulent relationships and her confusion and dread over her role as a woman paint her as a troubled archetype with nothing to hang onto. It’s a valid reality in its right, but it’s not the archetype that we need to be romanticizing.

It’s the archetype that disconcertingly aligned with my Tumblr days of reblogging Lana Del Rey, who was coined the “Vamp of Constant Sorrow” by Rolling Stone in 2014.

At the time, I worshipped “Play It as It Lays” for its ability to assure me that everything, no matter how glamorous or how painful, mattered only as much as I made it to be.

“One thing in my defense, not that it matters: I know something Carter never knew, or Helene, or maybe you,” Maria says. “I know what ‘nothing’ means, and keep on playing. Why, BZ would say. Why not, I say.”

I still stand firmly by the note that nothing has to matter, but I can’t stand firmly by looking at Didion without a bit of skepticism.

White women are allowed to be sad. But they’ve been allowed to be sad. Reading Joan Didion today brings us face to face with the depths to which inequality reaches.

Emotion, long the sexist differentiating factor between irrational women and rational men, has been redistributed along racial lines into valid and invalid experiences of disenchantment and depression.

![DePaul sophomore Greta Atilano helps a young Pretty Cool Ice Cream customer pick out an ice cream flavor on Friday, April 19, 2024. Its the perfect job for a college student,” Atilano said. “I started working here my freshman year. I always try to work for small businesses [and] putting back into the community. Of course, interacting with kids is a lot of fun too.](https://depauliaonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ONLINE_1-IceCream-600x400.jpg)

Ryan Air • Feb 17, 2020 at 12:32 pm

Love this piece! Joan is A Legend! Writer here captures her well