COLUMN: Movie theaters must adapt or die

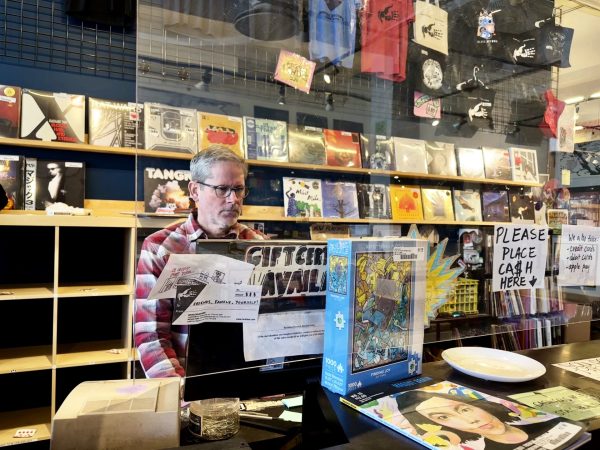

FILE- The Music Box Theatre, located in Lakeview.

I can remember the first time a film moved me. I can remember the first time a film truly terrified me. I can even remember the first time a film gave me a character I loved, and then quickly betrayed me. I love film and I miss going to movie theatres.

The rampant onset of COVID-19 onto the world has shaken our already insecure economic structures and further darkened our ailing hearts. Until very recently, movie theatres all across the country collectively shut their doors, many non-chain theatres reduced to crowdfunding for sustained support.

The pandemic was not the cause of their demise, merely an accelerant. Theatre chains were long failing to adequately compete with other sources of media. As soon as Netflix began producing films, the war on our attention spans commenced.

If the theatre-going experience is to exist beyond the murky fog of the pandemic, theatre chains, film studios and ticket buyers must change course and alter their behavior.

First, theatres must work diligently to make people feel safe going to the movies. Whether movie theatres are a safe place to cohabitate with other humans in the midst of a pandemic is outside my knowledge. What I do know, however, is that people will not return to the movies if great care is not taken to ensure safety.

This area is ripe for human error, but mandatory mask mandates, massive decreases in capacity and increased air ventilation are a must, not a maybe.

But the theatres cannot do this alone — exhibition is one of three major aspects of the film industry. Production companies and studios maintain control of production and distribution. These studios, now almost entirely owned by larger corporations, have the power to aid theatres through this massive transition.

For those reading who do not know (and I assume there are many), movie theatres only take a portion of the ticket sales of any given film. Usually, within the first two weeks of a major release, a given theatre would only take roughly 20-25 percent of the sale for each ticket. If you have ever wondered why concessions are ridiculously priced at theatres, it is because it generally amounts to 85 percent of a yearly profit.

Studios ought to allocate more of the profits towards theatres so that the cost is no longer passed onto the moviegoer. We know most of these studios are owned by multi-billion dollar corporations. They have the money, it can easily be spared. At least, if we want to save the movie-going experience we claim to cherish.

Studios should also produce more low budget, lower-risk projects. Much of their box office hopes are placed within the first two weeks, which is why we see a barrage of unoriginal, uninspired slop released in theatres each year — because it is the “safe” choice.

However, two production companies, Blumhouse and A24, prove just the opposite. A24 has carved an incredible niche for itself as a producer of quality, challenging films from interesting filmmakers. Films like “Moonlight,” “Hereditary,” “Lady Bird,” and “Uncut Gems” performed exceedingly well at the box office relative to their meager budgets.

Blumhouse is similar, producing many successful horror films, like “Get Out,” “Split,” and the “Purge” and “Paranormal Activity” franchises. The budgets for most of their films are so small that even critically panned films end up being successful.

These are not radical ideas. This was the norm for studios for decades: make several smaller budgeted films, mildly successful films in order to create room for larger tentpole projects. Not every project will succeed, but this way, the margin for error shrinks and output can remain steady. Studios should once again adopt these strategies if they want to help theatres, continue to profit and also draw new, and sometimes niche, audiences.

We as moviegoers have a role in this as well. We have become obnoxious and flippant. We act irrespective of other people’s feelings. Even sadder, is that this relates to not only how we behave at the theatre, but also in society writ large.

Going to the movie theatre becomes a far less enjoyable experience when people constantly use their phones. If I sound like I am preaching, it is only because the movies are my life. Long before the pandemic, the experience felt lost, corrupted by excess stimuli. If theatres have yet to die structurally, they almost certainly have spiritually.

Perhaps, though, theatres are meant to die. We are not as enthralled by the experience as we once were. Going to the movies used to feel magical precisely because of how they were perceived by our now overly stimulated minds. Now, we have everything. We can watch anything. And we need not pay a steep price to watch.

I do not want to spend the rest of my life remembering what it was like to go to the movies. I just want to go. I want to get to the theatre early to grab the perfect seat — up high, but not too high, centered slightly right. I want to pour M&Ms onto hot, buttery popcorn. I want to feel the weight of a great film shatter my soul, until it pieces it back together again, born anew.

Luckily, I believe that there are millions of people like me, who cherish the moviegoing experience. We do not want to see it go extinct. This may be our last chance to save it.