In Latin America, a deadly job for journalists

February 18, 2019

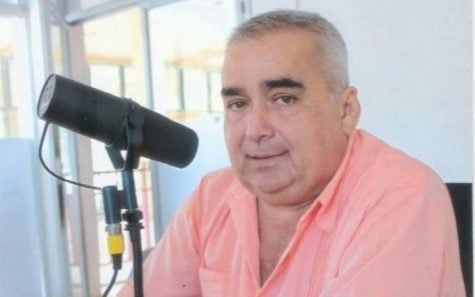

He was a radio broadcaster who had run his talk show, “Our Region Today,” for nearly 20 years in the Mexican state of Tabasco. Then on Saturday, Feb. 9th, as Jesús Eugenio Ramos Rodríguez was eating breakfast at the Hotel Ramos with former Emiliano Zapata mayor Armín Marín Sauri and two others, he was shot eight times by a lone gunman who appeared to be targeting only him. He later died from his injuries at a local hospital. Ramos, who according to local newspaper Tabasco Hoy was known to friends as “Chuchín,” is the second journalist to be killed this year in Mexico, a country that advocacy group Reporters Without Borders in 2018 called one of the world’s deadliest for journalists.

In their 2018 year-end report, the group noted that nine professional reporters were killed in Mexico with the probable motive being to silence them.

And according to non-profit journalism organization Insight Crime, Mexican journalists who report on crime, security and justice have been at an increased risk for violence in recent years — particularly when they are reporting on corruption and politics.

Mexico isn’t the only country in Latin America where reporters are not sufficiently protected.

Jesús Ramos Rodríguez, a veteran radio broadcaster for Radio Oye 99.9 FM in southeastern Mexico, was murdered as he ate breakfast Saturday, Feb. 9. The country is among the world’s deadliest for members for the media.

In 2013, Venezuelan reporter Luis Guillermo Carvajal was kidnapped by unknown assailants;. he had been doing journalism in his home state in Venezuela for nine years. He said that he “had been receiving threats for the work he did [and]people had wanted him to not speak on the government’s’ lies.”

Carvajal said the people who kidnapped him wanted for him to “disappear.” What saved him was government intervention from a mystery person he would never meet.

Carvajal said that after his release, the threats against him heightened — including threats saying drugs would be planted on him to make him look like a drug dealer. He would later move from his home state after being advised by the police to do so.

“I had a very strong fear, because I was being threatened by people that didn’t care about taking another person’s life” he said.

According to Impunidad Cero, a Mexican organization focused on holding criminals accountable through journalism, four out of every five homicides go unpunished and 90 percent of all crimes goes unpunished in Mexico. This may contribute to a gross under-reporting of crimes, including 93 percent of kidnappings last year that did not get reported to the authorities or even have an investigation launched, according to a report by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography, Mexico’s census and agricultural agency.

DePaul alumni and Insight Crime staff writer Parker Asmann said that Mexico and Venezuela “should serve as a reminder to journalists in the United States of the very real dangers that come with the profession around the world, and should remind us of how fortunate we are to have a certain level of safety and protection that allows us to do our job without the fear of reprisal, jail time or death.”

These fears are ones that DePaul senior Stephanie Mata sadly knows well. Her 32-year-old cousin Alonso Marquez of Guadalajara was kidnapped last year after going missing on July 16th, 2018; he was later found dead along with seven other bodies of women and children in a mass grave on Aug. 4, 2018.

Marquez, who was deported from the U.S. only four years prior to his death and who left behind three young children in America, ages two, six and nine, was working multiple jobs at the time, in the hopes of eventually returning to his kids.

Afterwards, his mother did not want to be a part of any more investigations because she was devastated by the death of her only son. Mata said her aunt “didn’t want to know who did it, or why; she just wanted to have his burial and get it over with.”

Mata said “there is a lack of trust of police in Guadalajara… police roam the streets, but bodies still keep showing up [in mass graves].”

Mata said that private Facebook groups have come into play to report crimes that traditional media cannot report on. The violence that pressures professional reporters into silence is now on the shoulders of everyday people.

“People in Guadalajara don’t know what’s going on, until it happens to them” said Mata. “And when the media does talk about finding 30 to 40 bodies, they don’t go into detail about how, why, or who.

“The people have a right to know what is going on, finding out the truth goes hand-in-hand with reconciliation and peace,” she added.

On social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, community members have been able to more reliably expose the truth of horrific crimes and government corruption because they cannot be pressured or identified so easily. Groups dedicated to spreading the word about those who have gone missing or are kidnapped are also common.

One anonymously lead Facebook page called “Valor por Tamaulipas,” for example, focuses exclusively on showing the truth and atrocity of crimes committed by the cartels in that state.

And in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, people have been using an app called “Fogo Cruzado,” or “crossfire,” that is dedicated to reporting real-time gun battles on a map based on first-hand-accounts, media information and police reports. The app is meant to keep civilians safe and away from active shooter zones.

These sort of tactics and resources are being used by everyday people because they know that no one else can do that for them at the moment.

According to Mexico’s National Commission of Human Rights, Ramos Rodríguez’s murder marks over 143 journalists who have been murdered in the country since the year 2000. And while the State Attorney General’s Office of Tabasco announced they have begun investigating the incident, many dangers for journalists in Latin America remain.

“It’s very rare that those who murder journalists are held accountable,” Asmann said. “Some Mexican towns along the US-Mexico border, such as in Tamaulipas state, have become so-called ’no-go zones’ for journalists because of the severe risks that come with reporting there.”

While there have been efforts to protect journalists, including a 2012 Law for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, and the 2006 implementation of a Special Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes against Journalists, the profession remains a dangerous and deadly one.