Marlee Chlystek | The DePaulia for The DePaulia

Juuls, teens and taxes

E-cigarette taxes aimed at eliminating teen nicotine use does a better job of preventing adult smokers from finding healthier alternatives

March 4, 2019

I enjoy cigarettes, I won’t lie. And I will admit that they have become sufficiently imbedded in my life. As I walk out the door each morning, I pat myself down and go through the checklist: phone, wallet, keys, cigarettes, lighter — the essentials.

Every so often people will ask me why I like cigarettes and there is really no good answer to that question. I just do. And it’s hard to be a cigarette smoker these days. No longer can you light up in bars or coffee shops (which, at 21, I was never able to experience, but I’ve seen “Mad Men” and all the Tarantino classics, and it looks nice). “Sin taxes” continue to intensify the financial burden on smokers in urban areas, and smoking in the year 2019 is more likely to leave you cold and alone on a rainy sidewalk than in an interesting conversation with a stranger. Not to mention the impending cancer and heart disease.

All of this makes for a decidedly terrible hobby — it’s suicide at a glacial pace. But in an effort to generate extra tax revenues and keep teenagers from becoming addicted to something they aren’t old enough to buy in the first place, the city of Chicago decided to levy extra “sin taxes” on e-cigarettes, one of the most effective anti-smoking products known to man.

“Tobacco and vaping is a public health nightmare,” Mayor Rahm Emanuel said when the tax was approved this past September.

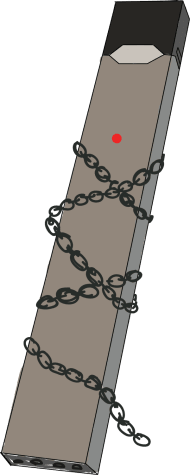

E-cigarettes have come under fire over the past year for their popularity among high school students. E-cigarette companies like JUUL, which makes a remarkably discrete, thin, black bar with a small pod containing nicotine oil clicked into the end, have specifically been called out for marketing their product to younger people with fun flavors like mango and mint and a perfect design for circumventing the rule of mom and dad.

“It’s no secret vape products, particularly easily hidden, flavored liquid products, have risen in popularity in recent years,” Emanuel said. “We need to counter marketing to prohibit youth access, and I am committed to expand restrictions on e-cigarettes, supporting youth to make healthy choices — and protecting residents from tobacco.”

John McCarron, an adjunct lecturer at DePaul and expert in local tax policy said that the motivation for this tax likely comes from two places. The first is a desire to increase tax revenue without hiking up highly unpopular property taxes by taxing consumers at the counter. The second is to discourage younger people from using nicotine products by jacking up the price. While some may see the latter as a cover for the former, McCarron says otherwise.

“It’s really more of a two-for,” he said.

But while protecting young people from the vicious addictive properties of nicotine is a necessary and worthwhile pursuit, using tax policy to get us there is misguided, particularly because making e-cigarettes less accessible only makes tobacco a greater threat to those trying to quit. The science behind how harmful vaping and e-cigarettes won’t be conclusive for some time, but most cancer research organizations, including the American Cancer Society, say that research suggests vaping is significantly less harmful than combustible cigarettes, which contain upwards of 7,000 chemicals.

A 2016 study on vapor products and tax policy from the Tax Foundation conducted by economist Scott Drenkard found that vape products have a much lower risk profile than traditional cigarettes, about 95% less harmful, according to findings issued by the British Health Department. That same study found vape product to be an effective method of quitting.

The most interesting finding, however, is that these taxes are inadvertently effective and preventing smokers from trying new alternatives, according to Drenkard’s analysis of every e-cigarette tax in the United States.

At The DePaulia, we have a handful of current and former smokers on staff and there is one thing we all have in common: e-cigarettes have us smoking less and less or not at all. We are all happier, and presumably healthier, but our wallets are starting to ache because Emanuel’s plan to tax teenagers out of the e-cigarette world has left us broke college students struggling to afford a healthier alternative.

There is an important and fundamental conversation to be had about the role of government and the merits of micromanaging people’s choices with taxes, but I think most would agree that a tax which prevents citizens from making their own healthy choices is a bad tax.