Adolescence and the issue with internet hoaxes

March 11, 2019

For people who grew up as the internet was first making its way into every home in the nineties and 2000s, there was no telling of what they were going to see. If a box popped up that said you can download some song for free, you clicked it and were surprised to see your computer had a virus. If post came along that said if you don’t share it with your friends, your mother will die within ten days, you shared it as fast as you could. If a Nigerian prince asked you to send him money, you very well might have. We were more trusting of the new medium because who would put such nefarious and dangerous content on something as young and innocent as the internet?

Now we are more dubious of pop-up ads and scam emails because we’re more educated on the dark corners of the internet, right?

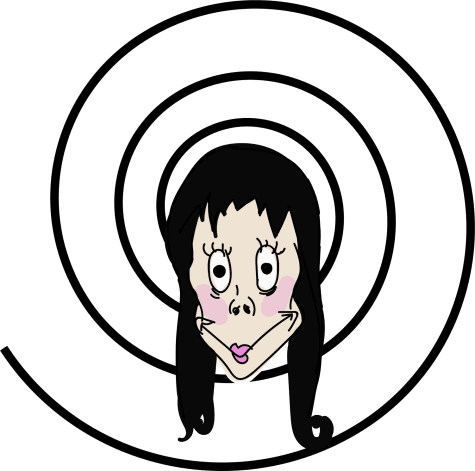

The latest example of our innate trust of the internet and subsequent fear of its ramifications is Momo, the viral fearmonger who instructs children on how to self-harm and commit suicide. Allegedly, she shows up unannounced in the middle of YouTube videos and teaches the kids a scary lesson, threatening them if they don’t comply. She supposedly even present on YouTube Kids, the childrens-only run-off of the popular video sharing site.

We know she isn’t some mystical and demonic being that plants herself into these innocent videos. The creator of the video places her image in the middle of a video in hopes that the parent will leave their child unsupervised to increase the chances that only the child will see it. Many parents leave their kids alone with YouTube Kids because it is supposed to “make it safer and simpler for kids to explore the world through online video,” according to the website.

“I don’t want to leave my kid with YouTube,” said Jania Staple, a 20-year-old Chicago mother. “But it really entrances and distracts him for a period of time so I can get some other stuff done.”

Staple is among many parents who use YouTube Kids as somewhat of an educational babysitter who can placate their overwhelming toddler years. According to data compiled by the business statistics website DMR, there were 8 million weekly viewers on YouTube Kids in 2017. But with thousands of videos being uploaded every day, some disturbing videos slip through YouTube Kids cracks. An article on this topic from Wired described multiple videos of iconic children’s characters like Minnie Mouse and Peppa Pig in situations that simulate cannibalism, suicide and torture. Eventually, this unnerving content gets deleted after users report it, but there currently isn’t a way to stop it before it gets uploaded.

This is where Momo comes in. Her internet presence was first reported around July 2018 by a YouTuber ReignBot. People were pretending to be Momo using the popular messaging app Whatsapp. They would send her picture to the kid and warn that if they do not follow her directions, she will come hurt them. It’s eerily similar to those scary chain messages that warn if the viewer doesn’t share it to their friends, someone will come and hurt or kill their family. Now, we look at those messages and laugh, but for a child to see the terrifying quasi-human that is Momo and hear her threats, creepy isn’t even the word to describe it. It’s complete, overpowering fear because these aren’t messages their parents prepared them for because they didn’t think they had to.

There haven’t been any reported deaths or serious incidents relating to Momo. Although her image might be burned into the minds of adolescents, the internet hoax cannot physically hurt them. But it can jade their relationship with the social and educational medium they have grown up with. Being exposed to disturbing images from a young age might lead to psychological disturbances or unwanted intrusive thoughts as an adult, according to Psychology Today. As with any intrusive image, like Momo, completely ignoring it only exacerbates the issue. Parents should discuss with their children about what they see on the internet to ensure their safety. Even if we can’t completely dictate everything a child sees when their online, we can help them understand that it isn’t all real.