On April 2, after two years of contentious negotiation between Iran and the United States, the two world powers arrived at a tentative outline in Switzerland that would place tight restrictions on Tehran’s nuclear program for the next 15 years. A final deal will be presented by June 30, after which it will have to survive both the U.S. Senate and Iranian Parliament to take effect.

On April 2, after two years of contentious negotiation between Iran and the United States, the two world powers arrived at a tentative outline in Switzerland that would place tight restrictions on Tehran’s nuclear program for the next 15 years. A final deal will be presented by June 30, after which it will have to survive both the U.S. Senate and Iranian Parliament to take effect.

In the weeks that followed, proponents of the deal praised the development as a chance to potentially ensure actual and longstanding stability in the region, while critics bombarded the effort as a means of letting Iran escape the sanctions that brought it to the talks in the first place.

President Obama, whose foreign policy legacy may rest on the success or failure of the Iranian nuclear deal, stated in an interview with the New York Times that the accord was a “once in a lifetime opportunity,” as well as “our best bet by far.”

In the meantime, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel has, as expected, come out as one of the most vocal opponents of the deal. Israel has long viewed Iran as an existential threat. On April 5, he appeared on NBC’s “Meet the Press,” saying, “I’m not trying to kill any deal; I’m trying to kill a bad deal.”

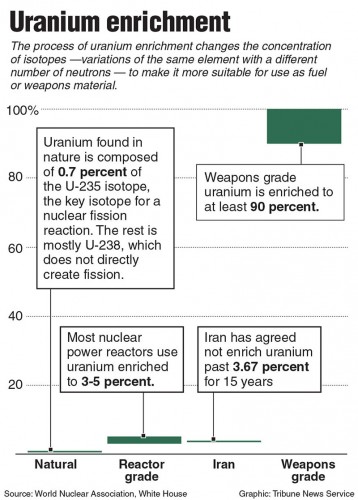

Many Congressional Republicans have also come out against the deal, concerned that Iran will not remain faithful to the terms set in the final agreement. The country has a history of concealing its nuclear military ambitions, most recently in 2009 when a secret uranium enrichment facility was discovered being built into a mountain near Fordo, Iran.

Last month, Republican Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas made major international headlines after sending a letter signed by 46 other Republican senators to the Iranian government, stating in no uncertain terms that an Iranian accord would not pass in the U.S. Senate. The move was labeled a “rare direct congressional intervention into diplomatic negotiations” by the New York Times, and met with fury by the White House.

Proponents concede that the deal may not be perfect: Israel and others have long argued that the complete dismantling of Iran’s nuclear program is the only acceptable solution. Kaveh Ehsani, a professor within the International Studies Department at DePaul University and a contributing editor of the Middle East Report, noted that even the energy portion of Iran’s nuclear program has failed to benefit the common Iranian.

“There is no accountability for the economic benefits of this very costly program, which is carried out in isolation from Iran’s own,” Ehsani said. “If energy was a primary interest for Iran, which is one of the largest holders of raw materials in the world — natural gas and oil — there would be many other alternatives: solar energy, wind energy, even tidal wave energies could be used.”

The absence of any deal at all means that Iran would be free to continue and possibly accelerate its efforts to build a nuclear bomb, despite retaining its current and severe sanctions.

“There’s almost an unspoken assumption that by keeping the sanctions on, we prevent Iran from getting a bomb,” Tom Mockaitis, a DePaul University history professor, said. “There’s no indication of that.”

He continued, saying, “The popular notion is that we just have to hang tough with sanctions… hang tough to what end? Dictators and authoritarian governments don’t suffer from sanctions; ordinary people suffer from sanctions.”

In an op-ed piece for the New York Times last month, former United States ambassador John Bolton argued to controversial effect that the only way to actually prevent Iran from obtaining a bomb was to bomb Iran’s facilities. Specifically, he stated that war “could set back its program by three to five years,” compared to the potential 15 years promised by the Obama administration’s deal.

Mockaitis referred to war with Iran as a “formidable undertaking,” but not an unthinkable one.

“We can do it. We have the ability to severely damage and perhaps even destroy many of their facilities, but such an attack might only delay rather than prevent Iran from getting a bomb,” he said. “It would certainly embitter people and perhaps strengthen their support for the nuclear program.”

War also appeals to the conservative establishment of both Iran and the United States, according to Professor Ehsani.

“You do have this continuation of a Cold War mentality that you need an enemy,” he said. “If your whole rhetoric for legitimizing your hawkish position… has been predicated on maintaining this evil, terrorist enemy, then you’ll be put into a position to rethink and have to explain how you’re making a deal with the devil.”

But simply coming to any agreement will represent “a big geopolitical shift” in U.S.-Iranian relations, according to Ehsani.

“If the accord is passed, Iran and the U.S. will have to make a deal and normalize relations on a host of other matters,” he said. “The U.S. will have to modify its position and question its existing relationships with existing allies.”

Arafat / Apr 14, 2015 at 11:04 am

Seeming to give credence to Orwell’s quip that “some ideas are so stupid they could only have been thought of by intellectuals.”