The Chicago Police Department (CPD) has a longstanding dicey reputation with residents of the city, but the fatal shooting of 17-year- old Laquan McDonald brought decades of mounting resentment and distrust to a head. Contradicting initial reports from officers at the scene claimed McDonald was walking towards officers with his three-inch blade when he was killed, but dashcam footage released to the public in December 2015 confirmed what many Chicagoans feared — McDonald was actually walking away from officers when he was shot 16 times by Officer Jason Van Dyke. Protests erupted across the city and citizens’ trust of both CPD and Mayor Rahm Emanuel plummeted.

In an effort to quell the unrest and outrage, Emanuel announced CPD officers would undergo mandatory “force mitigation” training classes in 2016. On Sept. 17 those classes officially began. Force mitigation training, commonly referred to as de-escalation training, teaches officers different ways of approaching potentially dangerous confrontations before turning to deadly force, according to the Chicago Tribune.

The same Tribune article reported that CPD’s force mitigation classes are led by Sgt. Larry Snelling and occur over the course of two days. The first day of classes focused on how to properly evaluate and approach situations in which citizens are acting erratically or may become violent. The conversations mainly focused on how to identify signs of mental health issues, the Tribune reported. During the second day, officers reviewed CPD’s use of force model and participated in simulated emergency situations to test their judgment.

In their training, Chicago officers learn more about the line between when deadly force is justified and when it is not.

“When we can reduce the risk of taking a life even if it’s a bad guy we should,” Snelling told the first group of Chicago officers taking the force-mitigation course, the Tribune reported. “We should not use force simply because we can. But when you are faced with an immediate threat and your life or someone

else’s life is on the line (…) you should respond with deadly force. You have to.”

DePaul senior Kennedy Bartley believes CPD’s force mitigation is necessary and long overdue. “Force mitigation training is absolutely necessary,” she said. “Oftentimes mental illness is criminalized because there is a lack of resources to properly de-escalate and treat these individuals. (People who suffer from mental illnesses) often find themselves in a justice system that won’t treat, benefit or rehabilitate them.”

Despite positive responses to Chicago officers undergoing this force mitigation training, the classes do not acknowledge another perceived issue with CPD and other police departments across the country: racial bias.

Despite positive responses to Chicago officers undergoing this force mitigation training, the classes do not acknowledge another perceived issue with CPD and other police departments across the country: racial bias.

“I think everyone is afraid (of police violence), especially young black men,” DePaul freshman Quinn Mulroy said. “When you hear about police shootings it doesn’t do much for the morale of the citizens. I think the problem of police confrontations escalating into violence certainly isn’t helped by both the police officer and the citizen hearing a million times every day that ‘Oh, this (confrontation) could easily escalate into violence.’”

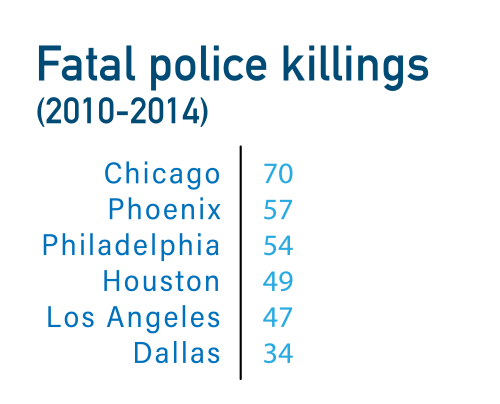

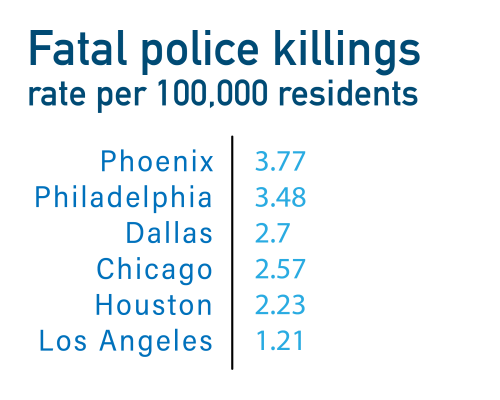

The issue is nationwide, but CPD has an especially high number of fatal police shootings. According to the Better Government Association (BGA), Chicago police officers fatally shot 70 people between 2010 and 2014 — more than any other department that provided data to the BGA. This statistic is slightly less stark when adjusted for population. Chicago has the fourth highest fatal police shootings rate at 2.57 killings per 100,000 residents. The Phoenix Police Department has the highest rate of fatal police shootings at 3.77 per 100,000 residents.

Bartley believes racial bias in Chicago’s police department results from improper education in racial issues and an inadequate amount of African-American and Latino officers.

“A main issue of the current system of policing is both a lack of representation as well as ignorance, because officers oftentimes aren’t from the areas they are policing or even from areas with a similar dynamic,” Bartley said. “They use a standardized system of policing that relies too heavily on the discretion of the individual officer. The ignorance comes into play when, due to systemic racist mechanisms such as the prison industrial complex, blacks and Latinos are seen as criminal solely based on their skin color. And because this innocence is stripped of them, officers find them to be hyper- aggressive or hyper-threatening when in actuality these things are reflective of the officer’s ignorance and, oftentimes, racism.”