Shortly after DePaul senior Sarah (who asked that her last name not be used) began taking the birth control pill the summer after graduating high school, she started experiencing undeniable signs of depression. Her “bad mood swings” became difficult to manage and she found herself withdrawing from her friend group, uncharacteristically preferring to spend time alone instead.

“I was told twice by my doctor, at three and six months on birth control, when I brought up symptoms of depression and anxiety that I was simply ‘adjusting’ to the medication,” she said.

For two years Sarah struggled with this so-called adjustment period before deciding the side effects of her birth control were too problematic.

“Since choosing to stop taking (the pill), my symptoms of depression have decreased severely and I have a more stable mood,” Sarah said.

It turns out Sarah’s experience may not be so uncommon. In a landmark study published last week by the American Medical Association journal JAMA Psychiatry, researchers found women who used hormonal contraceptives such as the pill had a significantly increased risk of experiencing symptoms of depression.

Led by Dr. Øjvind Lidegaard, a professor at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, researchers studied the health of more than one million Danish women between 15 and 34 years of age over a period of 14 years using data from Denmark’s National Prescription Register and the Psychiatric Central Research Register. Researchers excluded women who had already been diagnosed with depression before the study in their study results.

The study found that after six months, women using hormonal contraceptives had a 40 percent increased risk of depression. An average 1.7 percent of Danish women not using hormonal birth control began taking anti-depressants each year of the study. For women using hormonal contraceptives, the rate increased to 2.2 percent.

Similar to Sarah, DePaul graduate student Allie (who asked that her last name not be used) stopped using birth control pills after suffering from symptoms of depression.

“I’m not surprised by (the study’s) findings because when I was (on birth control) I did some of my own research about depression and birth control and found multiple blogs and testimonies that confirmed my feelings,” Allie said. “A few weeks after getting off birth control I began to feel immensely better and I knew that I had made the right choice.”

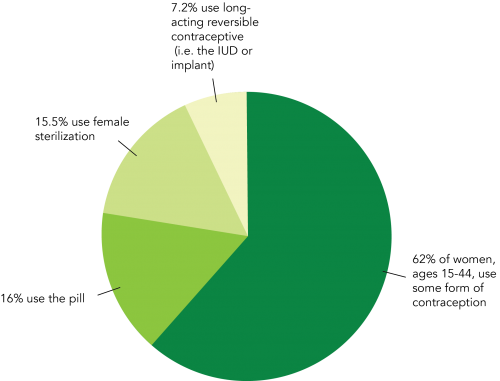

Although there are a variety of non-hormonal contraception options such as condoms and copper IUDs, many women use the pill for reasons other than birth control. According to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, birth control pills can be used to treat a number of issues including irregular, heavy or painful periods, endometriosis, premenstrual syndrome, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, acne, excess hair growth and hair loss.

In high school DePaul junior Mattie (who asked that her last name not be used) diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a disorder with no known exact cause according to the Mayo Clinic, but whose symptoms include “infrequent or prolonged periods” and obesity. Mattie began taking birth control pills when she was 16 to treat the disorder after her menstrual period lasted for almost a year and doctors feared she could become anemic.

Mattie began experiencing symptoms of depression from her birth control but did not have the luxury of choosing to stop taking them due to disorder.

“(My depression) was so bad that I had to switch what pill I was on five times in less than a year because I was gaining weight and was so unhappy,” she said. “For me personally, it was the progesterone in the majority of the birth control pills I tried that really messed with my body and my emotions (and it) didn’t actually control my period. So what I’m on now uses progestin, or rather a synthetic form of progesterone or something so it actually works the way I want it to and I don’t feel like a nutcase anymore.”

For Lidegaard, the adverse effects Sarah, Allie and Mattie experienced using hormonal contraceptives are unsurprising.

“We have known for decades that women’s sex hormones, estrogen and progesterone, have an influence on many women’s mood,” Lindegaard told CNN. “Therefore, it is not very surprising that also external artificial hormones acting in the same way and on the same centers as the natural hormones might influence women’s mood or even be responsible for depression development.”

Despite learning the results of Lindegaard’s study and experiencing symptoms of depression after using hormonal contraceptives, Sarah, Allie and Mattie all still maintain that women should make their own decision in whether or not to use hormonal contraceptives.

“Birth control is tricky and it’s a real toss up,” Allie said. “I think it all depends on the person and what their body can handle. After all, it is force-feeding yourself hormones.”