I am history because right now we are in the midst of a change in America and the way we act currently will headway the past and determine the events of the future.

As an African-American male student at DePaul University, I find myself having to adapt to many different environments, personalities and beliefs even when it is very condescending to my existence. Racism is rarely blatant anymore. It is more subtle (nowadays). We are no longer dealing with “whites only” bathroom signs or the “black codes” but black students deal with “passive inequality” in group projects, invalidation of movements that fought for their freedom and the appropriation of their culture daily. Why is it that non-black people who listen to hip hop music, a predominantly African-American genre, disagree with Black Lives Matter? How (is) it that group presentations with black students most o en lack black leadership? Which priest from our Catholic university will have the courage to address the “false visuals” of the saints, prophets and Jesus Christ we continue to display, knowing that original Hebrews were dark and brown-skinned?

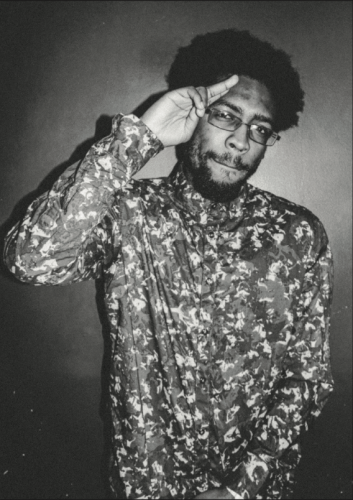

If we can’t address our own non-inclusive literature and rhetoric, who are we to denounce the statements of Donald Trump, who has decided to be straightforward in his beliefs on race and sex, yet has been met with backlash. I have tried my best to deal with this issue my whole college tenure and embarked on a number of campaigns through Men of Vision and Empowerment (M.O.V.E.), social media, activism and with my music as artist Mike Fulahope. Recently, on (social media), I have decided to post a sel e of a strong Black woman that I know every day for Black History Month. I did this to lay bare the academic success and personal attributes that manifest with Black females at DePaul. When we talk about Black history, the history of Black males tends to (surpass) the contribution of the Afro-female. My goal is to make renditions like these all the more common and I believe (this) will eventually lead us to a more socially acceptable world.

– Michael Brookins, President of M.O.V.E. (Men Of Vision and Empowerment)

I am history because of the history of my parents. e Caribbean slave revolts and revolutions proved to me that even though we may be held in bondage, we have strength in numbers. e steady independence of the country of Ethiopia was an a rmation of the governing power Black people have to self govern without colonial help.

When I was a child, the importance of Black history was displayed year round. I always attended a

predominantly Black school up until college, so the celebration of Black History Month was a 28-day holiday super embrace of my Blackness.

As I emerged in my Blackness, I had to realize a few things to ourish. My womanhood and my Blackness coexist, I never have to pick a side. Black people are the core and root of everything. America was built by Black people. Pop culture derives directly from Black culture. Fashion trends? Black people did it rst. We are innovators. e major lesson that took years for me to learn was that Blackness is not monolithic. ere is no “proper” way to be Black. If you are of African descent, you are Black. Your (interests) and hobbies do not discredit your Blackness.

S.T.R.O.N.G allows me to live in conjunction with their mission: to upli , empower and be a support system for Black women on campus (which) helps us cultivate the community we need at DePaul. Black history, or HERstory, starts with us. We Black millennials have a global advantage through social media. We have the opportunity to support and network with the Black Diaspora in a matter of seconds. Our Black history will be digital and revolutionary.

As we open our minds and intersect our history, there will be more marginalized Black people being highlighted, such as Black women, LGTBQ+ (and) gender nonconforming getting the recognition they deserve.

– Nyah Hoskins, Historian – S.T.R.O.N.G. (Sisters Together Recognizing Our Never-ending Growth)

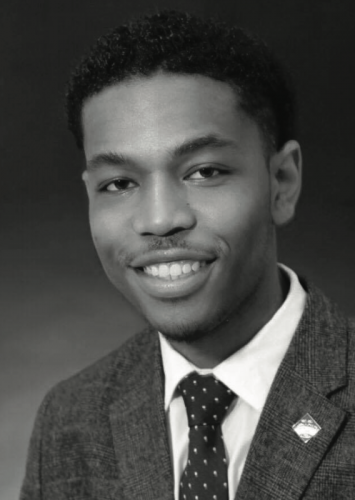

I am history because I was able to witness a Black man, a mirror image of myself, be sworn in as the president of the United States. I was in eighth grade staying up late with my parents waiting for the final votes to be tallied and then it was announced that Barack Hussein Obama would be the 44th President of the United States. As a young Black kid that was about to enter high school, this was such a euphoric moment. My confidence and the belief in my abilities to make changes in the world grew tremendously.

History is made everyday of our lives, whether we notice it or not. We all play major roles in history making but not everyone recognizes their personal contribution.

As a Black leader in today’s society growing up under the administration of a Black President, I’ve had the privilege to not only observe such a historical gure in action but also learn from him. I am history. President Obama has opened doors for African Americans around the world and this has empowered me to do my part in making history on DePaul’s campus. roughout my two years as president of the Black Student Union (BSU), I have seen many injustices occur to students of color. rough the hope President Obama has given me, I make it a point to advocate for marginalized students.

With the work currently being done by the executive board, we are creating history. Even though we may not see the end results of the projects we are starting during our college days, new boards will pick up the tasks and see them through. History is not always doing something for the ‘now’, but rather paying it forward for the future generations. I saw history take place and now I am making history happen.

– Mario Morrow, President of DePaul Black Student Union

I am history because I rise above the standard; the standard of complacency, of conformity, the standard of what de nes a black and Latina woman. I am history because I am the song of Nina Simone, the blood stains of cotton, the beat of a drum in “La Negra Tiene Tumbao,” the drive of escaping captivity and because I am the strength of my ancestors.

When I was ve-years-old in Bowling Green, Kentucky, I was told that I was stupid because I am brown. Today I am a consistent Dean’s list recipient, pre-med neuroscience major and a young woman who is proud to openly love her body and her skin. I have taken those words that existed to deter my excellence as initiative to excel as a leader, especially on this campus. (As) a Resident Advisor I have recognized how imperative minority representation is in leadership positions. I have the opportunity to engage with residents of all backgrounds and develop unique relationships that rede ne what diversity is. History has taught me in order to dismantle the narrative of what is “Black” (and) what is “Latinx,” I must leave my comfort zone and go against the grain. I o en think about if Audre Lorde never picked up a pen, if Rosa never stood her ground (and) if Harriet hadn’t guided me. Where would I be?

The strength shown by women like them has empowered me to continue towards my goal of increasing minority visibility in healthcare. My (passions) for women’s health, self-love (and) self-awareness (have) grown which is why I decided to audition in this year’s Vagina Monologues. It was on (a) whim, but my drive (was) to tell women (of) all shapes, colors, sizes and gender identities that their bodies are exquisite pieces of art. I want little black boys and girls to know that they can accomplish whatever they put their minds to. By being a leader on campus I acknowledge the responsibility I have to uplift other people of color at DePaul.

– Cara Anderson, Resident Advisor of DePaul’s Seton Hall

I am history because I am a byproduct of the work many of our ancestors have done, some of which are still alive. One person that comes to mind is Autherine Lucy. She was the rst black woman to try to integrate the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa because she wanted to earn her master’s in library science there. at was really important to me because she enrolled, but then she was expelled. is was a er the Brown v. Education ruling, so she had the right to be there but they expelled her anyway. She tried to reenroll and got expelled again, and wasn’t able to earn her degree until 1992.

inking about that I had the opportunity to work with supervisors of mine, that are women of color, who are also pursuing

their masters in library sciences and that

has been an in uence to pursue mine. It’s really important because the library eld is dominated by white women. It’s important to me to have that representation in libraries, to curate collections that re ect diversity so that anyone is reading books about other people so you can learn. at goes beyond race.

I’m currently pursuing my counseling degree here, and once I nish that the library science degree will be next. As a school counselor I’m really interested in how you can use books to make a di erence for students

in their social and emotional lives. Literacy can make an impact changing the lives of students of color. I want to have a long-lasting impact on students of color in Chicago.

– Kristin Lansdown, Access Services Circulation Student Supervisor at John T. Richardson Library

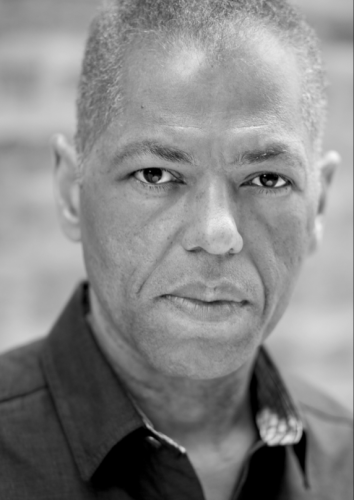

I am history because I’m an actor. is incident happened quite a few years ago back in the early 90s. I was out of town acting in a production of ‘ e Recruiting O cer’, an 18th century. restoration comedy. In it, I played a rustic who is best friends with another character who is also a rustic. Both characters supposedly are best friends, grew up together, are uneducated, dressed in rags and generally unkempt. e actor playing my counterpart was white and when we were both (called) in to speak to the costuming and make-up designer, the designer spoke at length to the white actor about how they were going to wig him so his hair would be long and shaggy (…) since these characters had likely never been to a barber shop.

When it was my turn to ask about what they were going to do with my hair, the costumer, who was white, only gave me a blank stare and with a wave of the hand, told me my hair was ne and they wouldn’t do anything to it. Mind you, I was sporting a tightly cropped high-top fade, a la Kid-and-play at the time. Nothing about my hairstyle suggested 18th century rustic.

However, it occurred to me that the white costumer could not fathom a wild and unruly Afro, which is exactly how my hair would have been considering the situation of the character. I learned in that moment that sometimes people will not see race (as) a way of not dealing with race.

– Dexter Zollicoffer, Diversity Advisor at The Theatre School