International headlines for you to know this week:

Trump’s health secretary resigns in travel flap

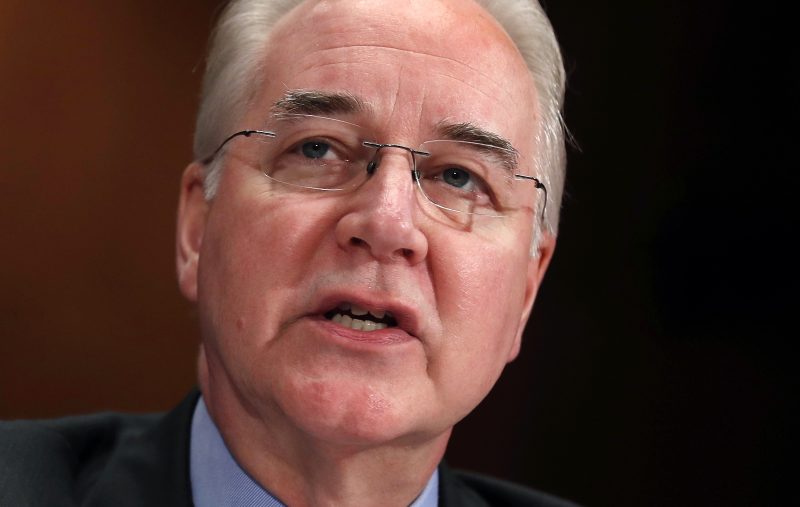

President Donald Trump’s health secretary resigned Friday, after his costly travel triggered investigations that overshadowed the administration’s agenda and angered his boss. Tom Price’s regrets and partial repayment couldn’t save his job.

The Health and Human Services secretary became the first member of the president’s Cabinet to be pushed out in a turbulent young administration that has seen several high-ranking White House aides ousted. A former GOP congressman from the Atlanta suburbs, Price served less than eight months.

Publicly, Trump had said he was “not happy” with Price for repeatedly using private charter aircraft for official trips on the taxpayer’s dime, when cheaper commercial flights would have done in many cases.

Privately, Trump has been telling associates in recent days that his health chief had become a distraction. Trump felt that Price was overshadowing his tax overhaul agenda and undermining his campaign promise to “drain the swamp” of corruption, according to three people familiar with the discussions who spoke on condition of anonymity.

On Friday the president called Price a “very fine person,” but added, “I certainly don’t like the optics.” Price said in his resignation letter that he regretted that “recent events have created a distraction.”

The flap prompted scrutiny of other Cabinet members’ travel, as the House Oversight and Government Reform committee launched a governmentwide investigation of top political appointees.Initially, Price’s office said the secretary’s busy scheduled forced him to use charters from time to time.

But later Price’s response changed, and he said he’d heard the criticism and concern, and taken it to heart.

Aid flows to Puerto Rico but many still lack water and food

Thousands of Puerto Ricans were finally getting water and food rations Friday as an aid bottleneck began to ease, but many remained cut off from the basic necessities of life and were desperate for power, communications and other trappings of normality in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria.

There were many people around the country, especially outside the capital, who were unable to get water, gas or generator fuel. That was despite the fact that military trucks laden with water bottles and other supplies began to reach various parts of Puerto Rico and U.S. federal officials pointed to progress in the recovery effort, insisting that more gains would come soon.

In some cases, aid that was being distributed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency was simply not enough to meet demand on an island of 3.4 million people where nearly everyone was still without power, half were without running water in their homes and the economy was still crippled from the effects of the storm that swept across the U.S. territory as a fierce Category 4 hurricane on Sept. 20.

“I haven’t seen any help and we’re running out of water,” said Pedro Gonzalez, who was clearing debris to earn some money in the northern coast town of Rio Grande. Increasingly desperate and with a daughter with Down syndrome to support, he had already decided to move to Louisiana to stay with relatives. “We’re getting out of here.”

FEMA was in the town the previous two days to distribute meal packets, water and snacks. But people said they hadn’t been able to get there in time. “This has been a complete disaster,” said 64-year-old retiree Genny Cordero as she filled plastic trash cans with water at the home of a neighbor who was among the lucky ones to have service restored.

Those who made it, however, were grateful. “This will help somewhat, so we don’t starve,” said Anthony Jerena, a 33-year-old father of two teenagers who had managed to get two boxes of water, each containing 24 bottles and, three packages of meals-ready-to-eat.

Yolanda Lebron, spokeswoman for the Rio Grande mayor, said they used a car with a loudspeaker to announce that FEMA would be registering people for aid, but did not mention there would be food and water given out. “We didn’t dare,” she said. “We didn’t know if we were going to have enough.”

Gov. Ricard Rossello and other officials said they were aware of people’s deepening frustration and of the difficulty, and danger, of living on a sweltering tropical island with no air conditioning and little to no water. He blamed some of the delay on the logistical challenge of getting aid shipments out of the seaports and airports, all of which were knocked out of commission in the storm, and then distributing the supplies on debris-strewn streets.

Rossello said Friday that the government would seize all food still sitting in containers at the port that private business owners had not yet claimed and would distribute it to people for free.

Myanmar refugee exodus tops 500,000 as more Rohingya flee

He trekked to Bangladesh as part of an exodus of a half million people from Myanmar, the largest refugee crisis to hit Asia in decades. But after climbing out of a boat on a creek on Friday, Mohamed Rafiq could go no further.

He collapsed onto a muddy spit of land cradling his wife in his lap — a limp figure so exhausted and so hungry she could no longer walk or even raise her wrists.

The couple had no food, no money, no idea what to do next. Their two traumatized children huddled close beside them, unsure what to make of the country they had arrived in just hours earlier, in the middle of the night.

Rafiq said their third child, an 8-month-old boy, had been left behind. Buddhist mobs in Myanmar burned the child to death, he said, after setting their village ablaze while security forces stood idly by — part of a systematic purge of ethnic Rohingya Muslims from Buddhist-majority Myanmar that the United Nations has condemned as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

Five weeks after the mass exodus began on Aug. 25, the U.N. says the total number of arrivals in Bangladesh has now topped 501,000. The crisis began when a Rohingya insurgent group launched attacks with rifles and machetes on a series of security posts in Myanmar on Aug. 25, prompting the military to launch a brutal round of “clearance operations” in response. Those fleeing have described indiscriminate attacks by security forces and Buddhist mobs, including monks, as well as killings and rapes.

“We don’t ever want to go back,” a stunned Rafiq said, describing his family’s ordeal as Bangladeshi volunteers stuffed a small wad of cash into his hand and gave their children biscuits. Another man offered a bottle of water, and Rafiq poured some into his wife’s mouth as she lay in his arms, staring blankly at the sky.

“This is not our home. It is not our country,” Rafiq said. “But at least, we feel safe here.”