Tobacco 21 bill rises from the ashes

Graphic by Annalisa Baranowski / The DePaulia

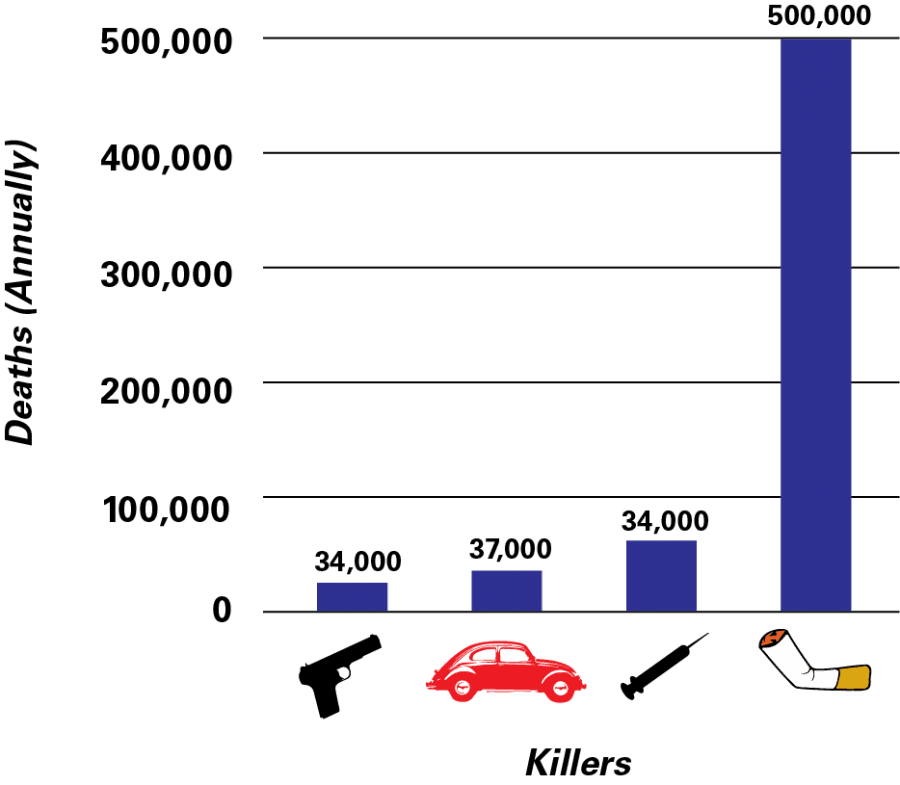

Among preventable causes of death, tobacco and nicotine related deaths far surpass that of drug overdose, car/traffic deaths and deaths by gun, including homicide, suicide, accidental shooting and undetermined cause.

Governor J.B. Pritzker signed the Tobacco 21 bill Sunday, April 7, which raised the legal age to purchase tobacco products from 18 to 21 years old. As Tobacco 21’s most affected age group, some DePaul students say they have mixed feelings about the new law.

“I don’t agree with smoking because of the health concerns it raises,” said Haedy Gorostieta, a DePaul sophomore. “But I think that raising the age could cause more problems. [The legal age to purchase tobacco] has been 18 for a long time, and those who have developed the habit will try to continue to do as they please.”

“Smoking just seems riskier than drinking or marijuana,” said Simi Rasp, a DePaul sophomore. “I’m sure both of those have negative side effects, but with tobacco it’s always been drilled into me that even one can have quite the impact.”

Since elementary school, the generation of students now barred from purchasing tobacco products has been told about the negative effects of smoking on the body, through programs like D.A.R.E. Medical experts say the dramatic effects “drilled into” students are just as bad as they seemed.

“The science is pretty clear that smoking can lead to a number of detrimental health outcomes like cancer, heart disease, and respiratory issues,” said Lourdes Molina, a health sciences assistant teaching professor at DePaul. “Smoking at a young age increases the risk of all of those, particularly if you become a long-term smoker.”

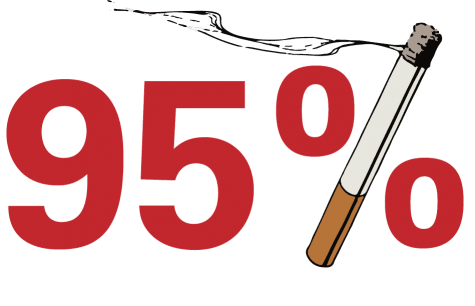

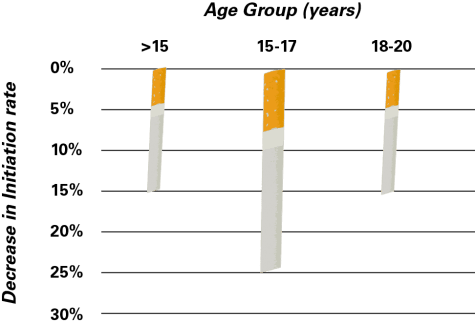

Many college aged people already smoke. More than 95 percent of smokers begin before the age of 21, and every day, 350 teens become regular smokers, according to Tobacco 21’s website. Chicago raised the age to purchase tobacco products to 21 in 2016, and since then, smoking between the ages of 18 to 20 has decreased by 36 percent, the website reports.

DePaul students are no strangers to tobacco smoking. Many of the school’s media have published articles discussing the use of tobacco on campus with titles like “Top 10 Places to Smoke on DePaul’s Campus,” and “To Smoke or Not to Smoke.” Students have even dubbed a staircase—the one directly to the right of the Levan Center’s entrance—as the infamous “smoking stairs.”

Though the new law will not likely deter students who already smoke, it might discourage young people from trying it.

“If you give people those three years, they could potentially go out and study those harmful effects,” said Ian Rios, a clinical assistant lecturer in DePaul’s nursing department. “If they decide at 21 they don’t want to smoke, we reduce the chance of all the high-risk diseases.”

Molina says that the law might be the most impactful ways to ensure young people’s health remains a top priority.

“I think one of the best ways we can regulate people’s behavior is through legislation,” she said. “And that can be a positive or negative thing. It can be perceived as government meddling or people not having a choice—you’re 18, you’re an adult and you should be able to make your own decisions—but sometimes, for some reason, people’s decision-making isn’t good for their health. If we are able to enact legislation that doesn’t give them a choice, it’s like a balance between people’s health and the government’s economy.”

But not everyone is convinced that the law is the best course of action to take. For the tobacco industry, it could lead to a dent in revenue.

“There have been some cities and counties who have done it, and in pretty much all cases, it has reduced the sales,” said Craig Klugman, DePaul professor of health sciences. “If you are in the tobacco industry, it will cut into your sales a little bit.”

Those numbers, though, come out to be rather low. Klugman says that according to multiple studies, raising the age would only decrease tobacco sales by about 2 percent, which would have been money made from students between 18 and 20.

In 2018, the Tobacco 21 bill was approved by both chambers, but was ultimately vetoed by then-Gov. Bruce Rauner, who said that the bill was pointless because kids would gain access to tobacco if they really wanted it. Many still agree with Rauner’s original argument.

“In an ideal world, it would prevent kids from getting access,” Rios said. “But we have laws at the federal level saying marijuana and cocaine are bad, and people still get their hands on that.”

“It’s not going to actually discourage smoking; it’s just going to make it more expensive,” Rasp said. “People, especially high schoolers, are just going to pay the hiked up prices of people who have access to tobacco and are looking to make a profit. That’s how it was at my high school anyway.”

Beyond the financial and physical benefits or detriments of the Tobacco 21 bill, many question whether limiting access to tobacco and other substances for 18- to- 20-year-olds makes sense given the other freedoms Americans are granted once they become a legal adult. At age 18, you can vote, adopt a child, get tattoos, change your birth name, and join the military, among other things.

“If the law is passed, you have 20-year-olds who can be shipped off to war and die for their country, and yet, don’t have the freedom to buy a cigarette or a drink,” Klugman said. “You can go die but can’t smoke or drink. There’s a question of fairness there.”