Who was mysterious Islamic State group leader al-Baghdadi?

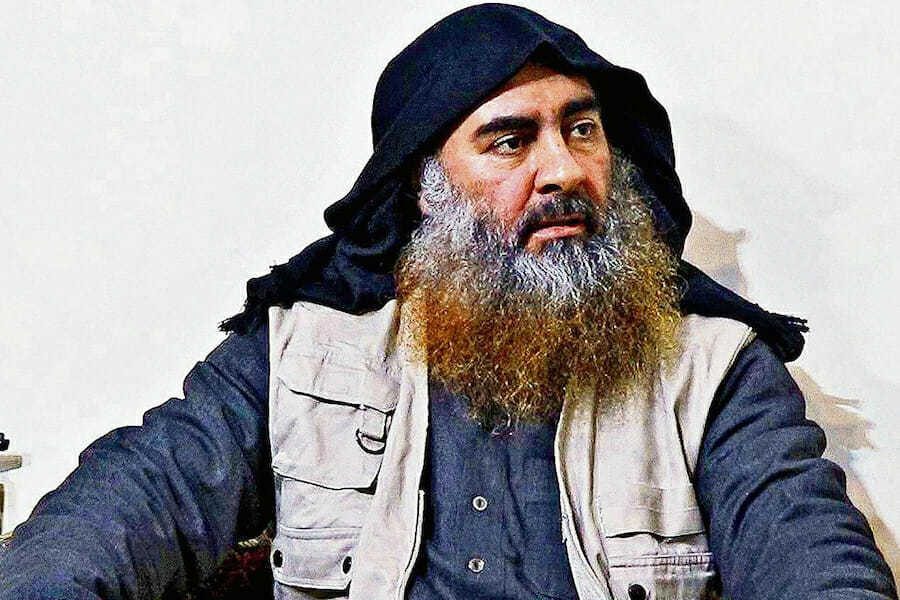

Department of Defense via AP for The DePaulia

This image released by the Department of Defense on Wednesday, Oct. 30, 2019, and displayed at a Pentagon briefing, shows an image of Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Before he declared himself caliph of the Islamic State militant group’s territory across much of Iraq and parts of Syria on June 29, 2014, and before he reportedly detonated a suicide vest — killing himself and several children as U.S. Special Forces raided a compound in the village of Barisha in Syria’s Idlib province — Islamic State group leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi proved a shadowy presence on the world stage.

Born in 1971 as Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim al-Badri in Samarra, he acquired nicknames such as “The Ghost” and “The Invisible Sheikh” because of his elusive reputation.

There are only two known photographs of Baghdadi before he became significant on the international stage. He kept a secretive profile throughout his control of IS. Even when addressing other commanders, he would often wear a mask.

“Since al-Baghdadi avoided public appearances and his whereabouts were unknown, false claims of his death occurred after all territory held by the Islamic State was liberated,” said Thomas Mockaitis, professor of history at DePaul University.

False reports of Baghdadi’s death emerged from 2015 to 2017 as Iraqi and Russian governments thought to have eliminated the self-declared caliph.

Baghdadi’s family claims to descend from the prophet Muhammad. His father, Sheikh Awwad, would teach children Quranic recitation which Baghdadi also participated in.

Baghdadi graduated from Samarra High School in Iraq in 1991. He continued on to receive his master’s degree at Saddam University and enrolled in doctoral programs for Islamic studies in Quranic recitation and Quranic studies.

On Feb. 4, 2004, Baghdadi was detained in U.S. detention facilities. First, he was held at Abu Ghraib before being transferred to Camp Bucca. Though many reports place Baghdadi in detention centers from 2004 to 2009, U.S. records show that he was detained for less than a year. He was listed as a civilian detainee because U.S. officials did not know who he was at the time.

DePaul political science professor Scott Hibbard, who specializes in Middle East politics, said the significance of Baghdadi’s time at Camp Bucca lies primarily in the people he encountered while in custody. There, he met self-identified jihadists and former members of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein’s military and security forces.

Experts have warned that American prisons in the aftermath of the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq often functioned as hotbeds of radicalization; the UN has declared that similar risks exist in refugee camps for IS families in eastern Syria.After much of the territory of the Islamic State was liberated, Baghdadi maintained a low profile. Much of his communication occurred through audio recordings on the organization’s social media channels.

“What really defines Baghdadi, is his ability to reshape this organization and the ability to capture territory and actually establish a caliphate,” Hibbard said.

He cited a number of historical caliphates — self-declared empires in which Muslims are called to live — the most recent being the Ottoman caliphate in 1924. Despite the stated scope of the caliphate, not all Muslims immediately flocked to these rulers. Thinkers at the time of the Ottoman caliphate questioned the claims of religious justification, and many caliphates were historically seen as a political rather than a religious concept. When the Ottoman caliphate fell, there was not a significant outcry for its return.

Baghdadi’s caliphate, under the rule of the IS, was brutal. The caliphate engaged in mass sexual enslavement of Yazidi women, decapitation of prisoners and punishments such as the removal of limbs for minor infractions within the organization.

But IS also created an effective bureaucratic system that in some ways proved more efficient than the previous government it replaced. It had a marriage office that provided medical examinations, ran its own DMV and even issued birth certificates.

The organization recruited civilians internationally, encouraging them to commit independent terrorist attacks. IS-inspired individuals carried out a number of high-profile terror attacks, including the 2015 Paris attacks, the 2016 Brussels attacks and the 2019 Easter bombings in Sri Lanka.

U.S. President Donald Trump formally announced the death of al-Baghdadi in the U.S. Special Forces operation on Oct. 27, 2019. This is a significant success because Baghdadi still had operational control in the underground networks, Hibbard said.

Hibbard acknowledged that this major success is largely due to the Syrian Democratic Forces that President Trump had abandoned to Turkey.

“This operation succeeded in spite of Trump,” Hibbard says. “Not because of him.”

Even with Baghdadi’s death, the Islamic State will continue to operate. On October 31, the Amaq News Agency formally acknowledged Baghdadi’s death and announced the leader of the new caliphate, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurayshi. So far, not much is known about him, though he apparently claims to trace his family history to the Prophet Muhammad as Baghdadi did.

Hibbard said that since the U.S. has not addressed the core political functions of extremism, the issue cannot be officially resolved.

“The U.S. military needs to think more holistically about how to deal with the problem,” he said.