Systems in place for survivors of sexual, emotional abuse at DePaul leave victims feeling abandoned

June 6, 2021

Content warning: This story includes mention of domestic and emotional abuse, sexual harassment, sexual assault and rape. If you or someone you know have been abused, resources are available via the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) at www.rainn.org. The National Sexual Assault Hotline is 1-800-656-4673.

Disclosure: Most of the names of survivors have been changed by The DePaulia for their privacy. The names of some alleged perpetrators of sexual misconduct have been changed by The DePaulia due to their status as students at the time of the incidents.

Rebecca sometimes works in the same DePaul building as her alleged abuser.

Amber’s perpetrator was found in violation of the university’s sexual and relationship violence policy — and was still promoted.

Jack had lewd photos taken without his consent in a DePaul bathroom.

Lauren didn’t want to report her assault — but rules at DePaul stopped her from making that decision for herself.

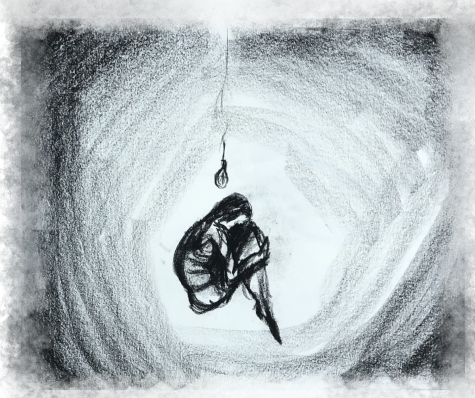

All four survivors, some of whose names have been changed to protect their identities, have more in common than their ties to DePaul. Each was failed by the systems put in place by the university intended to protect them from sexual and emotional violence and abuse.

In 2019, The DePaulia reported on the Title IX office’s accessibility and conduct when students suggested their cases had been mishandled. A two-year investigation by The DePaulia into the university’s handling of Title IX cases uncovered a pattern of negligence and disregard for the safety and emotional well-being of the DePaul community regarding sexual and relationship misconduct.

Title IX is a federal civil rights law that was passed as part of the Education Amendments in 1972. The law protects people from discrimination on the basis of sex in education programs or athletics that receive federal funding. Managing sexual violence cases is a large portion of the responsibilities universities hold under Title IX.

The new federal Title IX rules, put into effect in August 2020, altered preexisting university guidelines, adding a requirement of cross-examination — questioning by the opposing counsel — for both plaintiffs and defendants and eliminating all universities’ responsibility for handling sexual harassment “occurring off-campus, in a private setting, and outside of the university’s education programs or activities,” according to DePaul’s updated policy.

The university has said it will continue processing all reports of sexual misconduct, regardless of where they took place.

DePaul’s Title IX office is tucked in a corner of the third floor in the Student Center, a small space with fewer than 10 offices and a mid-sized conference room. Established in 2015, it provides protection on sex and gender-based discrimination such as “sexual harassment, sexual misconduct, sexual violence and gender-based dating and domestic violence and stalking,” according to DePaul’s website.

The office — presently made up of the Director of Gender Equity (Title IX coordinator), two investigators, a case manager and five deputy Title IX coordinators who offer support to the primary coordinator — has seen significant turnover in the last several years. The current Title IX coordinator, Kathryn Statz, is the third individual to hold that role in the last two years, and the other three individuals whose primary duties lie within the Title IX office joined during or after March 2020.

Incidents of abuse are not unique to DePaul. But the ways in which the university interacts with survivors of sexual and emotional violence and misconduct is in direct contradiction with the university’s Vincentian code.

While each story of abuse is different, each is reflective of a system that creates barriers for survivors of abuse at DePaul.

She wasn’t safe at home. Now, she feels unsafe at work.

Content warning: This story includes mention of domestic and emotional abuse. The National Domestic Violence Hotline is 1-800-799-7233.

Rebecca, an adjunct professor at DePaul, discovered in October 2016 that she was pregnant by her boyfriend, DePaul leisure studies professor Dan Hibbler, and moved in with him shortly after. By the following January, she was frightened for her life.

Throughout their relationship, Hibbler had been emotionally and verbally abusive toward her, diminishing her academic career and questioning whether the baby was his, she told The DePaulia. But on Jan. 4, the abuse verged on physical, according to testimony she gave the Kane County Sheriff’s Office at the time, per a police report obtained by The DePaulia.

Hibbler appeared to have been drinking all day, and when Rebecca returned home from work, he was agitated, she told the Kane County Sheriff’s office in 2017. After a quick spat, Rebecca thought that Hibbler had calmed down, so they planned to have dinner. Hibbler started eating without her, and when she sat down, he continued to make rude comments toward her, according to the police report.

He told her not to talk to him, and she retorted the same, the police report reads. Hibbler then “became enraged,” picked up his dinner plate and slammed it down, smashing the glass table, according to the police report.

Rebecca told the police she got up to get her phone, but Hibbler took it away, the report reads. He also took her iPad and the house keys off her key ring, according to the police report.

As Rebecca tried to retrieve her phone, Hibbler told her that he was going to “burn down the house” and that he “didn’t want to kill anybody,” according to the police report. Rebecca did not press charges, telling the responding officer that she “just wanted the incident documented,” the police report reads.

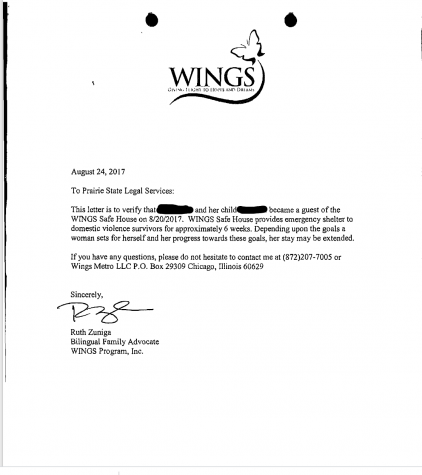

Two days after the incident, Rebecca called WINGS Safe House’s Community Crisis Center, according to documents from the center obtained by The DePaulia. She requested resources from the center, explaining the conflict. Several months later, Rebecca fled their home with their then-two-month-old baby after Hibbler allegedly verbally abused her again, according to a second police report.

The documents obtained from WINGS Safe House show she landed there on Aug. 20, 2017, homeless.

Hibbler did not respond to numerous requests for comment through multiple channels over the span of several weeks.

Rebecca said that she didn’t go back to DePaul the first quarter of fall 2017 out of fear that she and Hibbler would be scheduled to work in the same building. She confided her fears to her department chair, who advised her to report to Title IX, which she ultimately did, submitting documentation and photo evidence to back her allegations.

The allegations against Hibbler were as follows, verbatim, according to the Title IX office’s closing letter:

- Dr. Hibbler belittled and demeaned [Rebecca’s] academic background.

- Engaging in public discussions of [Rebecca’s] sex life, accusing her of infidelity and repeatedly questioning the paternity of their child.

- Calling [Rebecca] a bitch.

- Demanding [Rebecca] limit contact with her mother and with other friends.

- Demanding [Rebecca] contribute to household expenses, while demanding she not return to work after having their child.

- Using gift cards given to [Rebecca] for a baby shower to cover household repairs and purchase personal items for Dan Hibbler (shoes)

- Asking [Rebecca] to do household chores while recovering from a C-section

- Threatening [Rebecca] by stating “I believe you will die first” and “Most men understand men who kill their wives.”

- Engaging in physical threats and restraining her from leaving. Specifically, in January 2017 after breaking a glass table during an argument, Dan Hibbler stated “I hope I don’t kill anyone tonight” and “I will burn this place [their home] down.” He then retained [Rebecca’s] belongings (phone, keys, iPad) to prevent her from leaving or calling for help, which included him wrestling [Rebecca] while standing to obtain her phone. [Rebecca] was five months pregnant at the time.

- Entering [Rebecca’s] car without her permission.

- Following [Rebecca] to learn where she currently resides.

“At the time, it was Karen Tamburro who was the coordinator,” Rebecca said. “And initially getting in touch with her — it was very, I would say, proactive and aggressive. It was like ‘Yes, we take this very seriously and we’re very concerned. If you have any questions … like any time, please don’t hesitate.’”

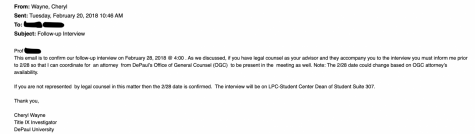

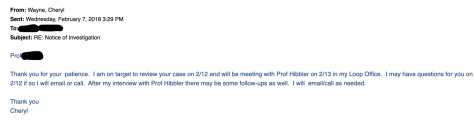

Rebecca’s case was assigned to then-investigator Cheryl Wayne, whom she thought was “fantastic.” But Rebecca soon started to feel that the office’s attitude towards her was changing for the worse.

“There was just a point where it just all sort of was going in one direction, and then just took a 180,” she said.

Rebecca said that in her next communication with the office, she felt an “attitude” and began to feel as though she was “bothering” the office by reaching out — despite their encouragement to reach out with questions or concerns.

“The whole shift, the whole communication [felt] like an annoyance, it was more of like, ‘Why are you bothering me?’” she said. “And of course, yes, it wasn’t verbally stated. But it was the whole tone in the response to things.”

Rebecca was scheduled to meet with Wayne on Feb. 28, 2018, according to emails obtained by The DePaulia. Before she could do this, Wayne had already arranged to meet with Hibbler.

According to Statz, DePaul’s current Title IX coordinator, the order by which parties involved in Title IX cases are spoken to is “informed by a variety of variables rather than a rigid, standardized approach to be used in all situations.”

Rebecca’s case was formally closed on April 30, 2018. The office determined the information provided by Rebecca was “insufficient” to prove the abuse took place in all but two of her claims — that she was expected to contribute to household expenses and that Hibbler entered her car without her permission.

“He would threaten to burn the house down, he would threaten ‘I hope I don’t kill anyone tonight,’ he would take my belongings away — and I reported this, I sent them everything,” she told The DePaulia, echoing her statement to the Kane County Sheriff’s office in a report.

Despite the office’s determination that Rebecca provided insufficient evidence, she felt the office did not do their diligence.

“I think [DePaul’s Title IX office] wanted to make it go away,” she said.

Tamburro, who is now the director of Northwestern University’s Office of Equity, declined to be interviewed by The DePaulia on numerous occasions. Wayne did not respond to The DePaulia’s request for comment.

Hibbler remains a tenured faculty member in the School of New Learning at DePaul, and Rebecca remains an adjunct professor, according to DePaul’s website.

He was found in violation of policy. Still, he was promoted.

Content warning: This story includes mention of sexual assault. The National Sexual Assault Hotline is 1-800-656-4673.

Disclosure: Amber has previously written for The DePaulia.

Amber Stoutenborough remembered being excited upon joining DePaul’s ROTC program; as a cadet her freshman year of college, she was befriended by older students in the program.

“When you’re younger, you know, it’s all cool,” she said. “You know, the older people are talking to me.”

The week before autumn quarter 2018 began, Amber went over to her friend’s apartment to hang out with others from the program, where everyone started drinking. Being one of only two freshmen at the party, she had less experience drinking than the older students and began to consume more after some lighthearted teasing to “keep up.” Later in the night, Amber was left alone in the room with Sam, a high-ranking senior in the program.

“He was flirting with me beforehand — it was kind of known, but I was like ‘I don’t know,’” Amber said. “I wasn’t sure about that because he’s [a high-ranking senior]… and he was a little bit older.”

Amber said Sam continued to flirt with her, eventually kissing her despite her vocalizing her apprehension.

“He kisses me and I was like, ‘I think I’m a little too drunk for this.’ And he’s like, ‘No I think you’re fine,’” she said. “…I just kind of — my whole body just froze up, basically. Couldn’t say no, couldn’t really do anything. I just was really drunk that I was almost falling off the stool, right? I couldn’t really say anything, [couldn’t] really move.”

He continued to kiss her, she said. As the situation escalated, Amber said she fell asleep due to her intoxication.

“I wasn’t kissing back,” she said. “And he was touching me in other places … I was very in and out. And then I black out; I don’t remember. I woke up on the couch and my underwear was gone. And I don’t remember anything.”

The day after the assault, Amber said that Sam texted her, saying he didn’t realize she was “that drunk” when he kissed her and apologized. Despite feeling uncomfortable about the situation, Amber said that she remained friends with him for two months following the incident, often hanging out in their friend group from ROTC.

Amber said she did not remember anything that occurred after blacking out, but never lost the feeling that something more had occurred that night.

“It felt nice to have that attention, but there was always like, the underlying feeling of this was wrong,” she said.

In October, Amber told her friend who had also attended the party about Sam kissing her; her friend said that while at the party, he saw her “completely knocked out with [Sam’s] hand down [her] skirt.”

Amber later confided in an older ROTC cadet, who then informed professors within the program. She was later contacted by Title IX, beginning correspondence in Jan. 2019. The back and forth between Amber and the Title IX office took place throughout the full academic year.

“I just kind of felt like they weren’t very empathetic towards the situation at all,” she said. “Like it was more of a business than anything.”

Amber’s case began that summer, taking place via video conferencing since she had to go home for the summer.

By the time her case ended in summer 2019, Jessica Landis, the Title IX Coordinator at the time of the investigation, was no longer at the university. Landis did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

According to documents obtained by The DePaulia, a different case worker informed Amber that there wasn’t sufficient evidence to take action on all charges. In regard to Amber’s claim that Sam kissed her without consent, the panel assessing her case determined it was more likely than not that Sam broke the university’s Sexual and Relationship Violence policy.

Sexual and Relationship Vio… by DePaulia

“Although initial instances of kissing may have been consensual, the panel found sufficient information to indicate that the reporting party’s capacity declined throughout the evening due to alcohol consumption, and the referred student knew or reasonably should have known that the reporting party was not able to provide clear consent,” the closing letter document reads. “The panel gave weight to the referred student’s statement in the investigation file that ‘I understand we were both intoxicated. How can it be consensual.’”

However, to Amber’s claims that Sam touched her elsewhere without consent while she was unconscious, the panel determined that it was more likely than not that Sam did not break the policy.

“The panel found insufficient information as it relates to these allegations,” the closing letter document reads.

Amber appealed.

“I wasted my whole freshman year having to go through that, just for nothing, so we did it again,” Amber said.

Her appeal was denied.

Amber said that she wished someone from the Title IX office had explained the reporting process more clearly before she committed to participating in it.

“It was very pressured,” she said. “I wish they treated me like an adult and actually talked to me so I [would be] able to do things instead of just sitting there and not being aware. I wish they had really listened to me, because it seems like it was just more of a bit.”

Following her reporting the assault, ROTC told Amber that she and Sam were to be separated within the program, with Amber stating that one stipulation required they were never in the same room. This was directly violated, however, when she saw him at both a celebration preceding the group’s military ball, and at the ball itself.

“I had no idea that he was going to be there,” she said. “I just felt like ROTC should have done more. Because [Sam] was spreading rumors, apparently, that I was just jealous [and] because I wanted to be his girlfriend that I started this. That was really hard to hear from every cadet because they knew about it. And it’s hard to hear that and then like, the officers did nothing about it. They just let it happen.”

Lieutenant Colonel Nick Bugajski served as the chair and professor of military science at Loyola University at the time of the case, where DePaul and several other area universities share a battalion. He declined to comment and directed The DePaulia to current leadership.

Lieutenant Colonel Nathan Lewis is the current Program Director of Military Science at Loyola. Lewis confirmed to The DePaulia that two DePaul students within the company were involved in a Title IX investigation during the 2018-2019 school year, and were “directed to have no-contact until the conclusion of the investigation,” claiming “standard practice.” He also confirmed that both students were allowed to attend a military ball “with appropriate mitigating measures in place.” Lewis said that he could not release any specifics of the case, but said that it was “the only [case he was] aware of” involving DePaul students during that school year.

Sam told The DePaulia that he was verbally instructed by company leadership to separate from Amber at program functions, but that he was given permission by ROTC leadership to attend the ball, with “strict instructions” not to interact with Amber. He denied that he told company members the allegations against him were born out of jealousy.

Amber later found out that Sam had been promoted alongside his graduating class, despite Title IX’s determination that Sam violated the university’s Sexual and Relationship Violence policy.

“I didn’t know that he was still allowed to be an officer after this, I didn’t know, actually, until the middle of my sophomore year,” she said. “Because nobody told me, nobody informed me of what was happening with him.”

Sam confirmed to The DePaulia that he graduated and commissioned before the final determination in the case was reached. He said that he felt the Title IX office was “inefficient at the time” and at times felt as though the office “wanted to get the case over with.”

“I didn’t really get a sense of urgency or a sense of care for myself,” he said. “…I don’t know how it was for the other side, but I felt as if they were just going through the motions and checking off boxes.”

He denied all allegations of sexual misconduct.

Amber remained in ROTC for the entirety of her freshman and sophomore year before eventually leaving in the middle of her junior year. She said that she trusts that the program is under better leadership now, but laments the ways in which they failed to support her.

“I was still really against them from what they did to me,” she said. “I tried to get past it, but it affected so much of who I was.”

‘How many other staff members and students have fallen victim to this?’

Content warning: This story includes mention of sexual harassment. The National Sexual Assault Hotline is 1-800-656-4673.

Jack, an employee at DePaul, was using a campus restroom in the DePaul Center in April 2019 when he suddenly noticed a phone peek under the urinal divider. When he realized that a student was attempting to take a picture of his genitals, he rushed out of the stall, confronting the student and calling Public Safety.

While Jack said that “no one was touched,” he said he still felt “disturbed” by the incident and went forward with reporting to the Title IX office.

“What also disturbed me about it was that [the alleged perpetrator] would go to such extreme lengths to get a dirty pic,” he said. “That’s creepy, you know what I’m saying? Like, how many other staff members and students have fallen victim to this?”

After reporting the incident, Jack maintained a five-month correspondence with DePaul’s Title IX office pertaining to the case, meeting with investigators several times throughout the summer of 2019. He expressed frustration about the “back and forth” nature of their communication.

“This office changes hands so much, no one wants to be there for some odd reason,” he said.

Jack first corresponded with the office shortly after the bathroom incident. He spoke with Landis, the Title IX Coordinator at the time who unexpectedly left DePaul in May 2019.

Following Landis’ departure, the office was manned by an interim Title IX Coordinator until September 2019. Another woman was then appointed coordinator on Sept. 9, before leaving the university in January 2020. Following her departure, former investigator Kathryn Statz stepped into the role, which she presently holds. Prior to Landis’ tenure as the coordinator, Tamburro — another former Title IX coordinator, who is now at Northwestern — held the role.

The Title IX Coordinator — now dubbed the director of Gender Equity — is primarily tasked with monitoring and overseeing implementation of Title IX across campus. This includes “training, education, communications and administration of complaint procedures for faculty, staff, students and third parties in the areas of sex discrimination, sexual harassment, sexual violence, sexual misconduct, domestic violence, dating violence and stalking,” according to DePaul’s website.

Communications obtained by The DePaulia showed that between April and August 2019, Jack communicated and met with Title IX investigators. After keeping steady communication with the office throughout the summer, Jack was told via email that the investigation’s next steps would involve hearing from the Dean of Students Office

“I am not certain that this will be immediate but more likely to be sometime next week,” the July email from Statz, an investigator at the time, read.

Nearly two weeks passed without word from either Title IX or the Dean of Students Office.

“I haven’t heard from anyone in the Dean of Student’s office,” Jack said in an email to Statz dated Aug 1. “This does not sit well with me.”

Later that day, Jack got an email from the Dean of Students Office letting him know that the office would be meeting with the accused student and requesting time to speak with Jack. After phone and email communication, the office asked Jack on Aug. 9 to “hold the morning of August 19” for a potential hearing date.

“The reason I say potential hearing is we are waiting to confirm a panel for the hearing,” the email read.

Jack agreed — only for the hearing to be canceled due to “scheduling conflicts with the panelists,” according to the office.

The individual who corresponded with Jack and previously worked in the Dean of Students office declined to comment on Jack’s case or answer general questions regarding timeliness of response.

Jack later reached out to Human Resources with his frustrations, and the hearing occurred on Oct. 11, 2019, six months after Jack made the report. He told The DePaulia he did not want the hearing to be delayed any further out of fear that he might cross paths with the offender while at work.

“Why is it like you’re protecting the perpetrator and it’s like giving me a hard time?” he said. “…Just imagine having to be in the same building as somebody who did something like that to you … And there’s no telling how many times you’ve got to cross paths because the Loop building is so small, and it’s only one building.”

Guidelines released in 2011 by the Department of Education said that if there are known instances of sexual misconduct, schools “[have] a responsibility to respond promptly and effectively” under Title IX.

“If a school knows or reasonably should know about sexual harassment or sexual violence that creates a hostile environment, the school must take immediate action to eliminate the sexual harassment or sexual violence, prevent its recurrence, and address its effects,” the policy reads.

In 2016, former President Donald Trump’s administration rescinded those guidelines, claiming they “led to the deprivation of rights for many students,” according to a Congressional Research Service report. Interim guidelines from the Department of Education in 2017 said there is “no fixed time frame” that constitutes the “prompt” investigation of sexual misconduct required under Title IX. Those guidelines have since been rescinded, too. Equally vague guidance on the definition of “prompt and effective” response was released in Oct. 2020; President Joe Biden’s administration has said it plans to review — and likely change — those guidelines.

Title Ix Rights 201104 by DePaulia on Scribd

According to Statz, DePaul’s current Title IX coordinator, prior Title IX guidance expected cases to be completed within 60 days. Though the present regulations do not specify that time frame, Statz told The DePaulia that the office still uses the 60 day framework as an “objective measure” and has been “successful in completing most investigations well within that timeframe over the last year (2020-21)” — roughly the amount of time Statz has held the coordinator position. Previously, she was a university athletic director until 2017, when she became an investigator, and was designated as a deputy coordinator in 2013.

After the hearing, Jack said the Dean of Students office called him to inform him of the student’s punishment, telling him that a signifier of the incident would be placed on the students records, and that employers and other schools would be able to see it. He said he was also told that the student was banned from the bathroom in which the incident occured. Jack said that he received no documentation regarding the student’s punishment and that he felt it amounted to a “slap on the wrist.”

“They said that [the harassment] is on the student’s record, so that whenever they try to apply for a job or go to another school, it’ll appear and they can make an inquiry into it,” he said. “But that just sounds like bullshit. Like, [there’s] no proof.”

She spoke of her assault. Her boss had no choice but to speak for her.

Content warning: This story includes mention of rape. The National Sexual Assault Hotline is 1-800-656-4673.

Lauren was raped on campus freshman year, but chose not to report. She told The DePaulia she had not fully processed the trauma and had heard that DePaul’s Title IX office “wasn’t really a great resource for survivors.”

In the fall of 2019, during her senior year, while at her job at the Loop Campus, she saw her rapist for the first time since the assault.

Feeling overwhelmed, she called her boss to inform her about the situation. The next day, she learned that her boss had reported the assault to Title IX out of duty as a mandated reporter.

Most DePaul employees function as mandated reporters to the Title IX office, meaning if they become aware of any instances of sexual harassment, assault or any other sex-based discrimination, they are required to report to the Title IX coordinator.

“I called my boss rightfully like freaking out was like, ‘I don’t know if I can run this event anymore, like freaking out,’” she said. “… But then the next day, my boss had told me that since I had told her essentially that I had been raped, that she had to report it to Title IX.”

Lauren said her boss took steps to ensure that she was comfortable following the mandated report. But that didn’t stop her from feeling that her voice was stolen.

“The right to report and have them know about it, it was kind of taken away from me,” she said.

The DePaulia requested comment from Lauren’s boss, who forwarded the query to DePaul’s media relations team — which declined to comment.

For many survivors of sexual harassment and assault, fear of handing over control of their trauma to a Title IX office can be a daunting barrier.

“People are afraid they’re not going to be believed, and sometimes they don’t want their perpetrator to get in trouble or to be expelled and they want to heal,” said Christine Zuba, a senior staff attorney for the Chicago Alliance Against Sexual Exploitation. “And maybe they want justice but they are afraid of this process no longer being controlled when they go to the Title IX office.”

After the report was made, Lauren received an email on Nov. 22 from the coordinator at the time, which notified her of the report. Lauren was provided a list of resources. After Lauren chose not to respond, the file was officially closed on Dec. 2.

The mandated reporting incident inspired Lauren to seek therapy, ultimately choosing to report the rape to Title IX in March 2020.

“I’m not really looking from them, honestly, any support or really like anything to happen to him, I just kind of want a record that, like, this happened,” she said. “Someone should know about it.”

Statz, the current Title IX coordinator, told The DePaulia that outside of mandated reporting, there are other avenues that offer victims more agency in reporting, including confidential reporting to factions of the university like Health Promotion and Wellness, University Counseling Services and University Ministry.

Mandated reporting applies to non-confidential employees – like Lauren’s boss. Statz said that if non-confidential employees are made aware of an alleged incident of sexual violence, they are required to report the following:

- The name of the person who reported the information to the employee;

- The name of the alleged affected individual, if different than the individual reporting;

- The name of the alleged perpetrator (if known);

- The names of others involved; and

- Any relevant facts that have been provided, such as date, time, and location. For instances involving sexual and relationship violence, the employee will also provide the reporting individual with a Sexual and Relationship Violence Information Sheet.

“Agency lies in the student’s decision about whether or not to share information about the person who caused them harm,” Statz told The DePaulia. “The impression that a responsible employee might push them to reveal information that they are not comfortable providing is one that I hope we can put to rest. That being said, another way of looking at this piece is that complainants/survivors have a right to know their resources and the best way to do so is by students being connected to our office, so we can make sure they know their rights and options under Title IX.”

After looking back on the experience as a whole, Lauren said she doesn’t think mandated reporting should be part of DePaul’s process.

“It completely took agency away from me,” she said. “The idea of having to report and having to tell people what happened just kind of made me feel pretty helpless and out of control.”

“When I knew my boss had reported, it was probably the day that I felt the most unsafe on campus,” she said.

Epilogue

It’s no secret that sexual violence runs rampant on college campuses. The National Sexual Violence Resource Center asserts that 1 in 5 women and 1 in 16 men are sexually assaulted while in college.

At DePaul, reports of sexual violence have been on the rise for years. In 2019, DePaul’s Title IX Coordinator — now named the Director of Gender Equity — received 88 reports of sexual violence, according to the university’s most recent Preventing Sexual Violence in Higher Education Act report. The year prior, they received 71 reports and before that, they received 60 reports.

DePaul University Preventing Sexual Violence in Higher Education Act Annual Report by DePaulia on Scribd

But the number of reports received by DePaul is likely not equal to the number of sexual violence incidents that actually take place among its students. Research suggests that number is significantly higher. Only one-fifth of all sexual assaults are reported among college-aged individuals, according to Department of Justice data.

“It’s not unique to the Title IX experience that survivors often aren’t believed or they don’t feel comfortable coming forward,” Zuba said.

Because the Covid-19 pandemic shut down campuses across the country, evidence suggests that reports may be made even less frequently — but that doesn’t mean incidents are happening less frequently.

“A lot of people are stuck with the idea of, ‘Well, if everyone’s quarantining, how can this happen?’” said Laura Palumbo, a spokesperson for the National Sexual Violence Resource Center. “That’s a misunderstanding of the fact that, you know, some students who may be on campus may now be more isolated because of the fact that there are less students, or maybe someone who is no longer able to live on campus has to have to find an alternative living situation that puts them at some risk — maybe someone was experiencing abuse by a family member or a partner.”

“You can imagine that Title IX complaints will get less attention from schools because schools have so much to deal with right now,” Zuba said, echoing Palumbo. “And I also think that maybe we haven’t figured out the best way to support students during this time when school is remote.”

Research shows that rates of sexual violence increase during emergencies, and some resource centers see up-ticks in calls for help. But when it comes to filing reports, some disaster victims see reporting as a “luxury issue – something that is further down on the hierarchy of needs,” according to sexual violence expert Beth Vann.

Publications NSVRC Guides Sexual Violence in Disasters a Planning Guide for Prevention and Response 0 by DePaulia on Scribd

While many incidents of sexual violence have likely taken place off campus amid the pandemic, that doesn’t necessarily mean the university isn’t responsible for supporting affected students.

“If we look at the broader framework of Title IX — it’s talking about the responsibility of campuses to not only effectively respond to students, but to promote the safety and wellbeing of students, faculty and all who are within their campus environment — then it is a responsibility that carries over into this new virtual context,” Palumbo said.

DePaul’s Title IX office is not the only office that processes and manages reports of sexual violence on campus. In a previous interview with The DePaulia, Landis said that reports may be redirected to other offices if they are “more fitted.”

“[The employee who connects with the student first] could potentially be someone else, depending on the nature of the report,” Landis said in 2019. “So it could be Health Promotion and Wellness following up, it could be the Dean of Students Office following up, it could be [the Title IX Coordinator].”

Still, a common thread between these four survivors’ stories is a lack of open communication between the office and the campus community, unclear disciplinary guidelines for acts of sexual and emotional abuse and an overall lack of trust that the office will ensure justice is served.

DePaul’s Title IX office is presently made up of the Director of Gender Equity (Title IX coordinator), two investigators and a case manager — a new position as of 2020. Those individuals are supported by five deputy Title IX coordinators who offer support to the primary coordinator.

“All of these professionals have been impactful and unwavering in their commitment to the DePaul community,” Statz told The DePaulia.

The office has seen significant turnover in the last several years. Statz, the current Title IX coordinator, is the third individual to hold that role in the last two years. Both investigators are also new to the department as of April 2020 and April 2021, respectively, according to Statz. The case manager, Hannah Retzkin, was previously a sexual and relationship violence prevention specialist in the Office of Health Promotion and Wellness, according to her bio. She joined the Title IX office in March 2020, Statz said.

Statz said that under her leadership, the office has worked to support students outside of sexual misconduct, as well, by assisting students who are pregnant or parenting and through partnerships with the LGBTQIA Resource Center to support students who have shared instances of potential misconduct involving gender identity and sexual orientation, also included under Title IX.

The office also received approval from all areas of the university’s shared governance to formalize the new Title IX Sexual Harassment Policy and Procedures.

“This was a testament to many at DePaul who worked tirelessly to memorialize very detailed expectations from the federal Department of Education into a document that is also DePaul-driven,” Statz said. “…We are proud of the hard work that has gone into serving our community over the past year.”

But on the fraught topic of sexual violence on campus, experts say there’s still work to be done — both at DePaul and elsewhere.

“Our society seems to struggle with sexual violence in a way — and accepting it and addressing it in a way — that it doesn’t struggle with all forms of violence,” Zuba said. “Part of it could be an unwillingness to just accept that anyone is vulnerable to this [or] an unwillingness to believe women.”

A comprehensive list of resources for sexual violence survivors of all backgrounds, compiled by the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), can be found here. The National Sexual Assault Hotline is 1-800-656-4673.

The Anonymous Afflicted • Jun 7, 2021 at 1:07 pm

I’m a DePaul student, and I was raped off-campus this year. The support given to me was a letter from Title IX saying that I was working with a case manager. That was it. That case manager did not offer resources or support or guidance. I wouldn’t be here today without RAINN and their hotline. Not CPD, not DePaul, not HPW, not Title IX. RAINN is the one who saved me. Thank you for producing and publishing this article. I’m actually one of your writers, and I’m just so grateful to you, my fellow peers, for shedding light on such a horrific problem within our University. Thank you. I stand with you in solidarity.

#MeToo