I am not fit to be a teacher, and I learned that the hard way.

It was spring 2021, my last quarter of high school. I just got accepted to DePaul and was planning to major in secondary education.

For the last few weeks of my senior year, I was a student teacher for an eighth-grade class at a nearby middle school. It was one of my first days, and the instructor asked me to give a lecture of half of the class. If I’m being transparent, I didn’t even know the material myself, so I was already an anxious mess.

During our discussion, I called on a student and asked if they wanted to write their answer on the whiteboard.

“Not really,” the student said, slouched down in his chair, arms crossed, glaring up at me.

It was at that moment I decided I did not want to be a teacher anymore. At that same moment, I gained an immense amount of respect for teachers.

Of course, I respected my teachers before this experience, but dealing with students first-hand and realizing that these are real experiences teachers deal with daily widened my perspective.

The challenges that come with being a teacher go far beyond dealing with difficult students — especially for those who are adjunct faculty. The part-time faculty members who are paid for each class they teach but, unlike faculty, do not receive benefits unless they teach a certain number of classes.

Colleges and universities nationwide are heavily reliant on adjunct faculty. According to the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America, adjuncts make up roughly one-third of all higher education faculty. Compared with the 916 full-time professors at DePaul, there are 1,400 adjunct faculty members, 800 of whom teach each quarter.

By hiring adjuncts instead of full-time professors, the university can cut salary and benefit costs.

Teaching on a quarterly basis can lead to sudden disruptions in adjunct’s teaching plans.

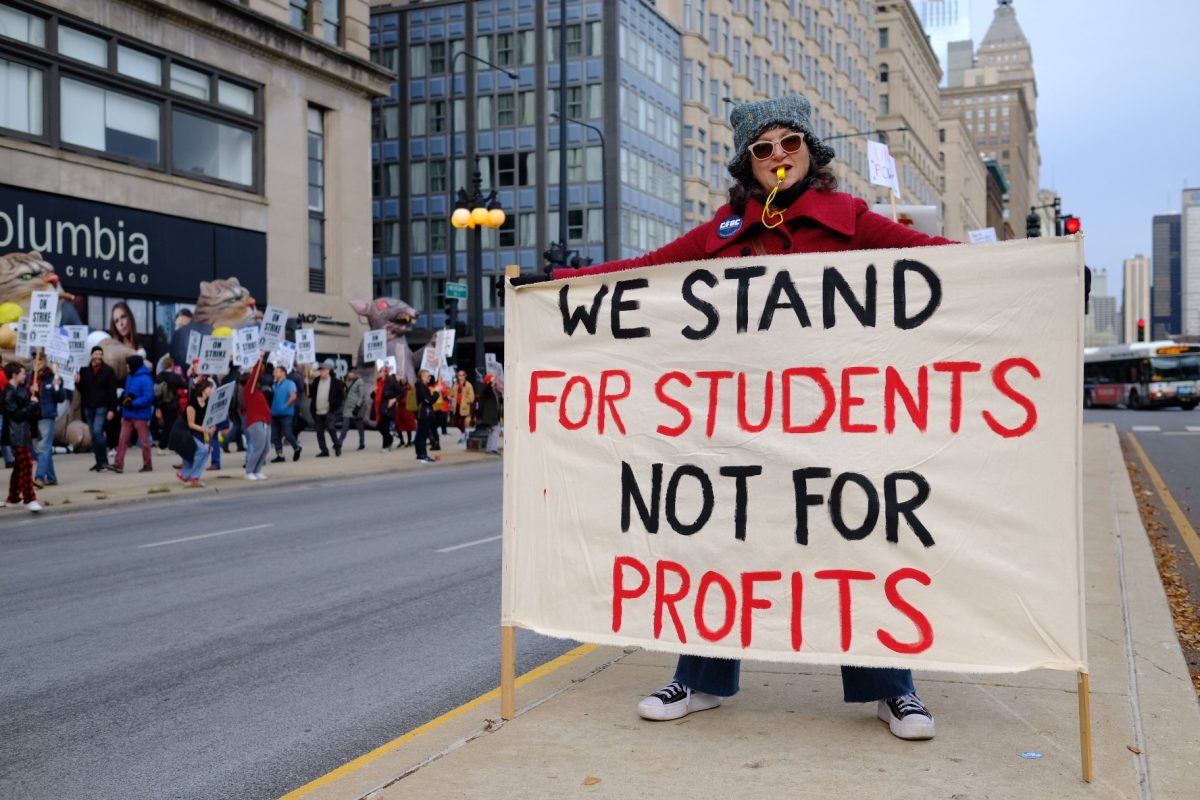

Last October, adjunct faculty at Columbia College Chicago decided to strike over potential cuts to classes, class sizes and other matters.

Columbia College Faculty Union (CFAC) had a contract with Columbia outlining the union’s expectations, such as protection of rights and compensation. However, it expired in summer 2023 and was never renewed, leaving them without protection once October rolled around and classes were abruptly canceled.

“It’s really unfortunate that the administration has put us in this position,” John Otterbacher, a Columbia adjunct and CFAC member, said when I interviewed him last November. “They could’ve negotiated, and they could’ve worked this out in August or September.”

Fortunately, CFAC reached an agreement with Columbia College Chicago. However, it sparked conversation among DePaul’s adjunct faculty and piqued my own interest in the plight of adjuncts.

While DePaul does not have a union, they have the Adjunct Faculty Advisory Committee (AFAC), which aims to address and resolve issues regarding adjunct faculty at DePaul.

“Several of the concerns include compensation, certainty of courses to be taught and benefits,” said Fred Mitchell, AFAC member and adjunct professor in DePaul’s College of Communication.

Job security is also of concern for adjunct professors.

Gabrielle Simons, a DePaul adjunct and AFAC member, addressed this in a comment under a 2020 DePaulia story about adjuncts getting contracts quarter to quarter.

“If we perpetuate a caste system where more than 50% of [DePaul’s] faculty operates without job security, we negate our mission and our ideal of universal dignity,” said Simons, who teaches writing, rhetoric, and discourse.

“If we all got abducted by aliens, DePaul would have difficulty functioning,” Simons said in an interview. “They’re counting on us to show up, and they’re counting on us not to strike or do a walkout. It’s the good nature and the dedication to teaching of our adjunct faculty that we don’t do that.”

Thankfully, DePaul has made some effort to put these concerns to rest.

For example, health and benefit welfare programs are offered to adjuncts who are credited with the hours equivalent to teaching a load of at least six four-credit hour courses in a 12-month period.

According to DePaul’s associate provost for Academic Planning and Faculty Lucy Rinehart, there are additional steps to better address the concerns of adjunct faculty.

Rinehart said the university can “continually strengthen communication with adjunct faculty, ensuring that they feel included in the academic communities … are aware of the resources available to support their work … and have clear channels for communicating and addressing concerns and issues that arise.”

This is not to discredit the amount of work that all staff and faculty members put into their jobs at DePaul. The important thing to recognize is that a lot of adjunct professors are working professionals, who often work elsewhere to make ends meet.

“I’m a filmmaker. I have movies that are in production and film festivals,” said Otterbacher, the Columbia adjunct. “I do post production work, I get hired to shoot videos.”

Every single employee at DePaul works extremely hard, and every professor, full-time or part-time must be recognized for their great efforts and skill. But when I was covering the strike at Columbia College, I saw how those on the picket line were deeply affected. And while they still had concern and care for their students, they had to stand by each other. That is the kind of dedication that adjunct professors bring to higher education.