On Feb. 26, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ruled in favor of strong net neutrality rules by classifying the Internet as a public utility. According to FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler, it is a historic step towards preserving the “fast, fair and open Internet.”

The measures are part of an attempt to prevent telecommunications providers such as AT&T and Time Warner from blocking web content they don’t approve of, as well as selling the fastest Internet speeds to giants such as Google or Netflix.

During the vote, Wheeler said, “The Internet is simply too important to allow broadband providers to be the ones making the rules.”

Following the ruling, telecom companies were quick to cry foul and accused the government of overbearing regulation and overreach. At the same time, proponents of net neutrality weren’t exactly thrilled either.

Jacob Furst, professor from the College of Computing and Digital Media, supported the notion of a free and open Internet alongside many other web users. However, he doesn’t believe the FCC has come anywhere close to true “net neutrality.” Stronger rules were actually demanded by President Obama last November after rumors began to circulate in Washington, D.C. that the commission was considering weaker regulations.

According to Furst, in the real practice of complete neutrality, “ISPs, or Internet Service Providers, would essentially be like the telephone.” Providers would simply be “carriers” of the Internet, like the wires that transport electricity or the pipes that transport natural gas.

This metaphor does not quite do the Internet justice, however. Whereas most public utilities are responsible for a single service, such as water, electricity and others, the Internet throws out conventional wisdom by providing “content.” In the eyes of the FCC, this is grounds for regulation.

It’s not absurd for the telecommunications industry to be upset about the ruling. After all, there’s nothing unusual about paying for higher speed and higher quality Internet — it’s a reality that most American consumers are used to.

The second part of the ruling dictated what was most important to net neutrality. Without the FCC’s regulation, an ISP is able to slow down a competitor without reprimand, which is what Comcast has done to Netflix since early 2012 after relations between the two soured. Netflix is one of the largest sources of Internet traffic in the world, accounting for over 34 percent of North American web traffic in 2014, according to the Wall Street Journal.

It is unclear what the Internet would look like without these regulations going forward, given the sheer youth of the Internet. Furst said that it’s entirely possible a lightly regulated free market could protect the American consumer from abuses from the telecommunications companies.

“If the market can protect consumers, then you don’t need the government; government interference is likely to make things fairly screwy. But we don’t know,” Furst said.

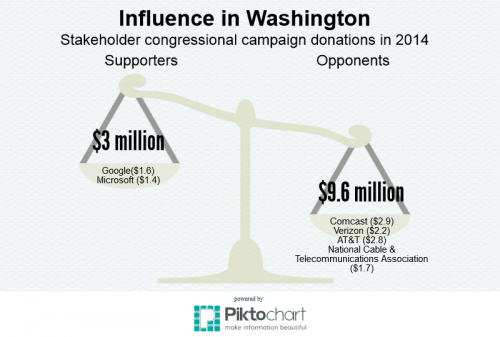

The FCC has yet to publicize the exact legislation that will put these rules into effect, and policymakers expect heavy resistance to emerge from conservative lawmakers in Congress as well as the powerful Silicon Valley lobby.

Although many believe that the FCC’s ruling takes the necessary first steps towards true net neutrality, the battle over the Internet is far from over.