Antonio Morales-Pita, a DePaul economics professor and former economic policy consultant in Cuba, remembers his decision to leave the country.

“I poured my soul out for my country, spending years trying to solve the (economic sugar) problem. My solutions fell on deaf ears because they were not ‘Castro approved’,” he said. “Later, I returned (from assignment in Mexico) for what was supposed to be seven days. They took my passport and kept me for seven months … I decided, ‘I need to leave.’”

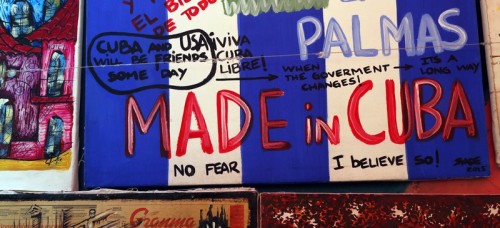

Fast forward to 2015. U.S. President Barack Obama and Cuban leader Raul Castro concluded a recent round of negotiations that would set forth a number of policies meant to further re-normalize relations between the two nations. This all occurs amidst a climate whereby some pundits believe that Cuba itself has been softening its communistic economic and political policies since the transfer of power from Fidel Castro to his brother Raul in 2007.

As a result of the talks, the Obama administration removed Cuba via executive order from the United States’ list of states sponsoring terrorism. Furthermore, the discussions opened up the possibility of establishing formal embassies between both countries as well as the hope of repealing the economic embargo against Cuba, which has been in place since 1962. The latter two would require Congressional approval.

“The way things are going right now, however, I doubt any President would be able to get three-quarters of Congress to end (the embargo),” Felix Masud-Piloto, a DePaul history professor and Cuban émigré, said.

The recent negotiations were one of many events that have been part of the normalization between the two nations since the Obama administration took power. In 2009, the administration lifted certain travel restrictions for Cuban-Americans and other individuals, and certain limits on transfer payments from Cuban émigrés to Cubans — a major source of income for many families still living in Cuba — were also lifted.

While addressing foreign treatment of Cuba, Morales-Pita said, “Remember, the Cuban people are not the same as the Cuban government.”

Interestingly enough, DePaul boasts a study abroad program in Havana, Cuba, that predates the start of diplomatic normalization in 2009. According to Masud-Piloto, who also helps run the program, the upcoming trip this summer would be the seventh in the program’s history.

“Our trips are very much facilitated through the University of Havana. I have a lot of good contacts and friends there, and these people help address and interact with our groups,” Masud-Piloto said. “One of our groups actually met Fidel Castro in 2001. We were at a big art opening, and he showed up right there. He kissed one of our DePaul students on the forehead.”

Masud-Piloto remained uncertain of how these newfound diplomatic developments might affect DePaul’s program there, but hoped that it would increase the speed of bureaucracies with tasks such as granting travel visas.

“Undoubtedly, however, for other travelers who don’t have connections, it will make things easier,” Masud-Piloto said. “In addition to cultural travel, American business opportunities could increase in the next few years … Hopefully this will be for the better.”

The normalization of relations between the two nations could lead to potential further development of capitalism in Cuba. However, some people wonder whether lasting political change will ever occur in the governance of Cuba, and with some preserving lasting memories of the pains suffered under the Fidel Castro regime, such qualms remain legitimate.

“Cuba was, arguably, one of the worst countries in the world to be in. People lacked any semblance of free choice; where to work, how to be productive and contribute to the good of their own nation,” Morales-Pita said. “With a Castro still in power, I doubt this will change soon.”

Regardless of widely varying émigré opinions on the developments in Cuba throughout the years, there is a shared hope that newfound ties between the nations will lead to lasting improvement, not just for American business opportunities, but for the average Cuban.

“I remember looking down from the plane (when I left), thinking ‘I love my country.’ And I wept,” Morales-Pita said. “I just want the climate to improve enough for my return someday.”