The term “non-racist” has been floating around social media recently as a result of a video published by The Guardian.

The video details the differences between being non-racist and anti-racist. Non-racism is characterized by a moral objection to racism absent of any action to end racism, whereas anti-racism is characterized as being morally opposed to racism and turning that moral objection into the fuel for progressive change. Anti-racism is taking responsibility, taking action, and affecting meaningful structural change.

Right now, an integral component of policing reform in Chicago is about to meet its fate on the desk of Cook County Circuit Judge Peter Flynn. Unions that represent the Chicago Police Department (CPD) are pushing for the destruction of disciplinary files that date back to 1967, backed by the argument that under the police union contract all misconduct files should be destroyed five years after any given incident. A decision made at a hearing on Jan. 15 gave both sides until March 15 to agree on a system that decides which records are preserved and which are destroyed.

According to the Associated Press, “Flynn said Friday that he will eventually have to consider whether the state’s Freedom of Information Act requires the city to release material it shouldn’t have had in the first place.”

More recently, allegations have surfaced of police officers tampering with dashcams to inhibit audio recording. Particularly in the dashboard footage of 17-year old Laquan McDonald, who was shot and killed by Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke, the lack of audio is haunting.

According to DNAinfo Chicago, “On 30 occasions, technicians who downloaded dashcam videos found evidence that audio recording systems either had not been activated or were ‘intentionally defeated’ by police personnel, the records show.”

Whether it is the destruction of records that are key in determining which officers have a history of misconduct or the possible tampering of dashcam footage, there is undoubtedly an issue within CPD. Officers within the department must have something to hide, and as taxpayers and concerned citizens we have the right to know what exactly it is that they are hiding.

Although there are groups of passionate activists and journalists fighting for transparency, many Chicagoans seem detached or unconcerned regarding matters of police misconduct. The overarching reasoning behind our stagnant nature tends to be misplaced hope in our policy makers, or even more prevalent, a sense of disconnection we feel between police misconduct and our own lives. If it does not directly affect us, we seem to lack the necessary sense of urgency when it comes to dramatically transforming policing practices.

There is no sense that we are connected to these issues on any deeper level, no sense that we play a role in the system that is responsible for the disproportionate murders of black Americans by the police.

Oftentimes, where there is a strong moral objection to police brutality, there is an accompanying feeling of innocence. While you may be disturbed hearing news of police brutality, personally you do not feel guilty. After all, you didn’t kill anyone. You didn’t pull the trigger on the gun that took another person’s life, so what more can you offer than your condolences?

What seems to be absent in this reasoning is the fact that many of us benefit from the same system that is responsible for killing our neighbors. While people of color continue to be targeted by the police, many of us continue our lives absent of the constant fear that plagues people of color on a daily basis.

In a study conducted by The Guardian in 2015, “young black men were nine times more likely than other Americans to be killed by police officers,” which resulted in a “final tally of 1,134 deaths at the hands of law enforcement officers this year.”

Our silence and inaction is only encouraging this behavior. It is not enough that you oppose the lack of accountability. It is not enough that you cringed when you watched the video of Laquan McDonald’s tragic death. It is not enough that you care. It is not enough. This is a call to action, a call to realize that things will not change so long as we continue playing the role of concerned citizens absent of any action.

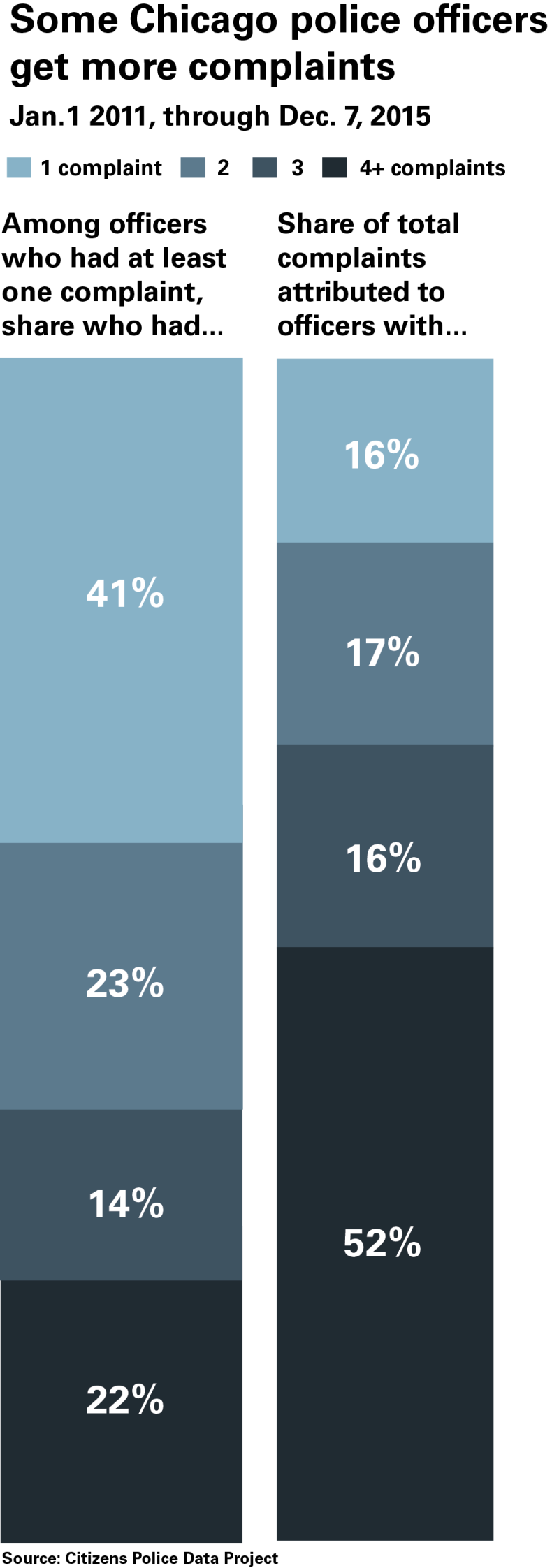

According to the Citizens Police Data Project, of the officers who have received at least one complaint between Jan. 1, 2011 and Dec. 7, 2015, 22 percent received four or more allegations of police misconduct. The officers who have received four or more complaints made up more than half of the total complaints received.

If years of disciplinary files are destroyed, the history of unaccountability is destroyed. If you are on the side of the unions, think carefully about your position. Is it a mere coincidence that the initiative to destroy these records came after major investigations were launched to investigate the Department’s practices? Isn’t it the public’s right to know what has been hidden for all these years?

To be perfectly clear, this is not an indictment of all police officers. This is an indictment of a system that continuously allows its police officers to go unpunished for committing crimes. This is an indictment of a society that watches while it happens.

Fortunately, there are organizations working to combat the lack of transparancy within CPD. The Invisible Institute’s Citizens Police Data Project was recently given a $400,000 Knight News Challenge on Data grant to grow its existing online database of police misconduct reports and allow residents to file complaints online.

John Bracken, the Knight Foundation’s vice president for media innovation, sees the Internet as a major tool for communities demanding police accountability.

“The work The Invisible Institute has been doing feels like a national model for a way transparency can serve the public,” Bracken said. “As this project grows, a key component is to engage the community and have them share their experiences. They don’t rely just on a digital component — they have a way for the community to share and engage and that’s at the core of what they plan to do.”

If we want to see change in our society, in our policing, we need to initiate a major paradigm shift. We need to abandon non-racism and embrace anti-racism. We need to stand in solidarity with those who are affected by this horrendous police misconduct. We need to demand transparency in our policing so we can then demand accountability.