Kelsey Cruz, a sophomore math major, commutes to DePaul from Skokie, driving an hour to and from the Lincoln Park campus on days when she has classes. Though she is part of the large community of commuters, she’s also part of a smaller population — students who are first-generation.

There have been numerous studies documenting the struggle, as well as the triumphs, of first-generation students at various universities. Some show the hard time many have acclimating to college campuses and culture — dorm life, class schedules and increased work loads — others show the psychological effects, mostly documenting the importance of support groups and networks for students.

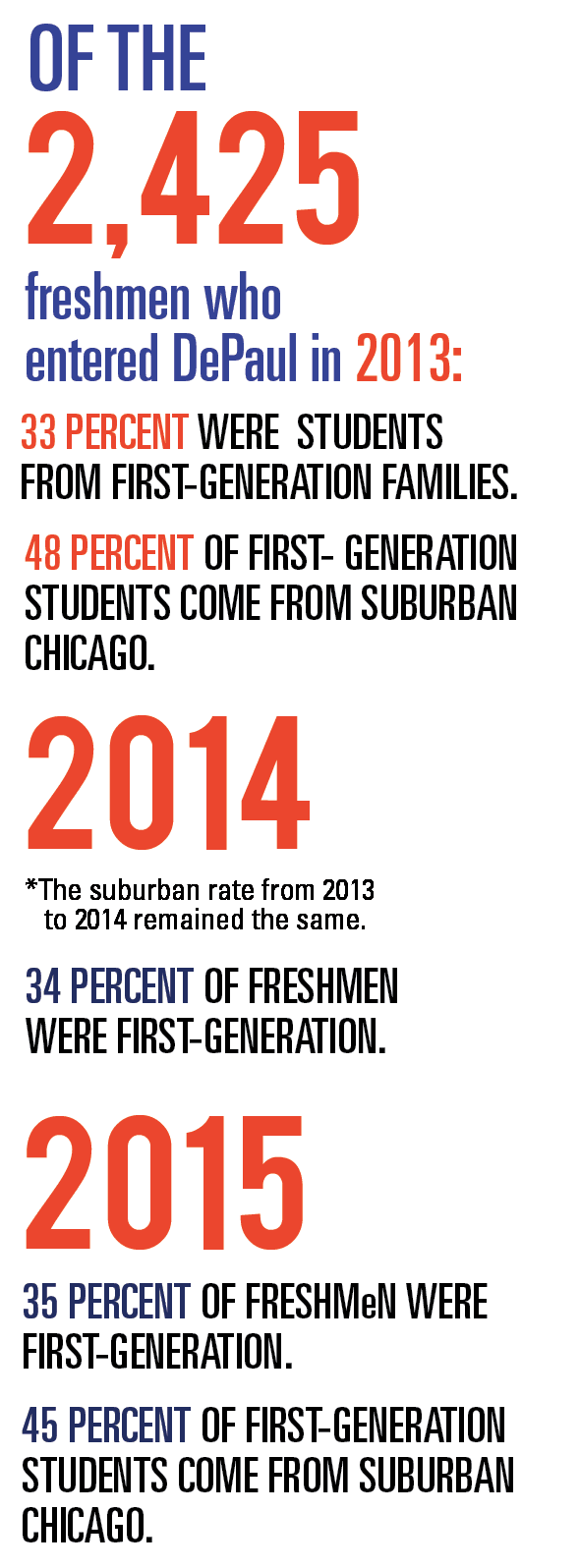

DePaul presents options for both, and judging by a steady influx of students from CPS and other schools around the city and nation, the plan seems to be working. Last year, the university’s enrollment summary reported that 35 percent of students in the freshman class were first-generation. That percentage has held relatively steady: in the 2014 report, 34 percent of the freshman class was first-generation, in 2013 that number was 33 percent and in 2012 first-generation students represented 31 percent of the overall freshman class.

Cruz’s situation is unique because her mother went to school in Colombia, but her degree didn’t transfer over to the U.S. Growing up, higher education was a topic of regular discussion in her house.

“It was never an option to not pursue it because we all agreed on the importance of college and its correlation with opportunity in the U.S,” Cruz said. “I do think you could argue first-generation students have a heightened appreciation for their higher education because they’ve seen firsthand how many doors can be closed without a degree. I don’t think non-first-gen students have the same conversations because they haven’t had the same exposure to the risks of not having a specific degree in the U.S.”

Opportunity obtainment is also the focus of the Office of Multicultural Student Success (OMSS), which focuses most of its efforts on first generation students. The main goal is to provide them a sounding board through their time here from becoming accustomed to the university to negotiating a salary with a potential employer.

“We try to help them know what to expect during this experience, and that they are not alone. Some students have to reconcile their place in the family and the work or school work they have,” Kimberly Everett, director of the office, said. “All we do is affirm that people should be here. We’re here to help all students, but first-generation and low-income students are a main part of our charge as an organization.”

OMSS also offers other groups specifically for men and women of color, the EXCEL initiative that promotes academic success, PATHS, which focuses on career opportunities and helping students during their job-hunt and STARS, a peer-to-peer group that allows freshmen first-generation students to connect to older mentors.

DePaul also partners with organizations around the city to recruit first-generation students and help communities. The Cristo Rey Network, comprised of 26 Catholic, college-preparatory schools, is “committed to serving underserved students,” Kenneth Hutchinson, director of college initiatives, said.

“There’s a lot of talented students and we serve to help them be on the same playing field as their peers who may come from a higher socio-economic background, or whose family members attended college,” Hutchinson said. “Even once they reach college, we want them to be able to have a voice on the other end of the phone saying ‘stick it out, it’s going to be okay.’”

Though DePaul is doing its best for the communities represented at the school, the experience itself can be hard to handle.

“I think college can be an overwhelming experience for anyone, but when you’re a first-generation student you’re molding your own path without anything to compare it to. That leads to a certain pride, but also a gear of not being able to maximize your experience because you don’t have specific familial guidance,” Cruz said. “Knowing the value of a degree just goes back to perhaps seeing parents not being able to prosper in certain careers because of that higher education gap. The inability to advance within a working class.”