DePaul brought a rather unpopular human rights issue to the forefront on Wednesday, hosting a discussion called “Guantanamo Bay & the Tea Project.” The discussion, facilitated by DePaul’s Center for Public Integrity Law and University Ministry, featured three speakers who actively advocate for the rights of detainees currently being held at the Guantanamo Bay prison in Cuba.

The speakers included artist Amber Ginsburg, human rights activist Aliyah Han Hussain and writer Larry Siems. All three individuals are involved with the Tea Project, an ongoing series of performances and exhibitions meant to showcase beauty in times of war and oppression.

Aaron Hughes, an Iraq War veteran, started the Tea Project in 2009. Hughes was disturbed by how people living in the U.S. had become so disconnected from the war and how the victims of war were being dehumanized. He wanted to bring people together over tea to examine the issues of war, oppression, beauty and art.

Hughes, in collaboration with Chris Arendt, a former guard at Guantanamo Bay prison, began a special type of sculpture and performance art involving porcelain Styrofoam cups. While working at Guantanamo, Arendt fell in love with the art and floral designs inmates would draw on the Styrofoam cups in which their daily tea was served.

In 2013, Hughes and Arendt invited Amber Ginsburg, who specializes in social sculpture, to help sculpt 779 uniquely designed, porcelain Styrofoam cups in recognition of every prisoner who has been held at Guantanamo since its opening in 2002. These cups now serve as a symbol for the struggle of Guantanamo inmates who have been stripped of their rights.

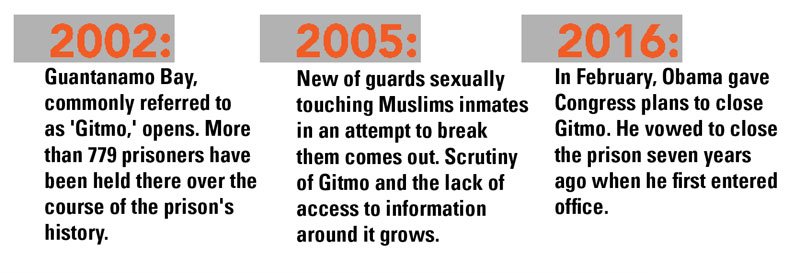

Guantanamo Bay has been a controversial place for most of its 14-year existence. The prison opened in 2002 during the war in Afghanistan to detain men suspected of being terrorists or involved with terrorist groups. The prison’s location on the island of Cuba, not on U.S. soil, allowed the U.S. to deny detainees the rights they would be granted by law if held in the U.S.

Siems and Hussain have spent the past several years examining the legal and moral implications of holding prisoners indefinitely at Guantanamo.

Siems and Hussain have spent the past several years examining the legal and moral implications of holding prisoners indefinitely at Guantanamo.

In 2012, Siems received a 466-page manuscript written in English by Mohammad Ould Slahi, an inmate at Guantanamo. The pages were only declassified after a lengthy legal battle and more than 2,500 redactions were made. Siems spent two years editing the manuscript before publishing it under the title “Guantanamo Diary” in 2015, having never met the original author.

“Guantanamo was created specifically in order to allow censorship,” Siems said. “The things that we did to men in Guantanamo are prohibited by the Geneva Conventions, they’re prohibited by the convention against torture, they’re prohibited by U.S. law, so you can only do them in secret.”

Unlike Siems, who has never been granted access to the prison, Hussain traveled to Guantanamo numerous times. As a human rights advocate with the Center for Constitutional Rights, Hussain’s work has focused on getting inmates fair trials or released to third party nations.

“Not only are there these misconceptions of who the men are in Guantanamo that persist … (there are) also people (who) might know about Guantanamo but they just don’t feel a connection to it,” Hussain said. “What many of us are trying to do in our work is to try to get people to have a connection.”

Today, a total of 89 men are being held at Guantanamo. Two men were released and resettled in Senegal on April 4, but there are still 35 men who, despite being cleared for release, are still being detained at the prison.

Lubna El-Gendi, the director of student affairs and diversity at DePaul, said it is hard not to be pessimistic about the fate of the men still being held at Guantanamo.

“Even if it closes, it’s just going to be internalized,” El-Gendi said. “I think it’s still important … to not let the public forget about it and about what’s happening and to get the stories of the detainees out.”

Montgomery Granger / Apr 11, 2016 at 4:31 am

How about some balance? The U.S. military detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, is legal, ethical and moral. While I served there as the ranking U.S. Army Medical Department officer with the Joint Detainee Operations Group, Joint Task Force 160, ICRC p[physicians I worked with told me “no one does [detainee operations] better than the United States.” No one is perfect, but there is no better place for unlawful combatants than Gitmo. Even lawful combatant POWs may be held, without charges or trial, until the end of hostilities, as per the Geneva Conventions and Law of Land Warfare. Those who want to release dangerous unlawful combatants are not offering to care for them and are just trying to manipulate the political will of the U.S. There is another side to this argument, a real side. Sincerely, Montgomery J. Granger, Major, U.S. Army. Author: “Saving Grace at Guantanamo Bay: A Memoir of a Citizen Warrior.”

arcticredriver / May 9, 2016 at 12:23 pm

Major Granger, you amaze me with your willingness to repeat the same transparently untrue apologies for the shocking US detention program, over and over again, long after the weaknesses in your arguments have been exposed. Here, you write: /”Even lawful combatant POWs may be held, without charges or trial, until the end of hostilities, as per the Geneva Conventions and Law of Land Warfare.”/ While it is completely true that POWs can be held, without charge, until the end of hostilities, you know full well that the George W. Bush Presidency took the highly controversial position that they would not classify the Guantanamo captives as POWs.

You and I both know why they did this. Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld incorrectly thought they could torture their captives, for as long as they wanted, so long as they claimed they weren’t entitled to POW status.

This cuts both ways. Since the Bush position was that they weren’t POWs as per the Geneva Conventions, then the USA had exposed itself as human rights violator by not laying charges against those who could be charged, and releasing the rest.

As for the care the captives now need – you have a lot of nerve to demand that other parties provide that care when you and your medical colleagues stood by and watched those men being tortured.