Leon Venable, owner and chief operating officer of the Kalimba House Corporation, didn’t really know about the Oxford House program until he needed it most.

While he was recovering from his addiction, he lived in one of the organization’s houses — the first in Illinois — for three years as he found his bearings and moved back into the community, finding jobs and a support system, as well as founding Kalimba, which provides training and education under the Oxford House Model, one that emphasizes a community approach to addiction treatment and creating an independent, supportive and sober living environment.

For Venable, DePaul professor Leonard Jason and his team of students in the community psychology program have helped him along the way as he too begins to spread the model of Oxford Houses around the country.

Jason and his students do research on the Oxford Houses and how they help former addicts get back on their feet. The research they’ve done have helped the organization, but also former addicts as the nation moves to address substance abuse.

“Our relationship grew into one of mutual respect,” Venable said. “(Jason has) taught me many things over the years and helped me understand. It’s been a great journey and I had no clue until we started.”

Since then, Venable said, Jason and those who do research showing the effectiveness of the Oxford House model have turned the movement for reassessing halfway houses and addiction treatment into a national one. Jason has worked for over 25 years doing research on how the organization helps the people who call the houses home.

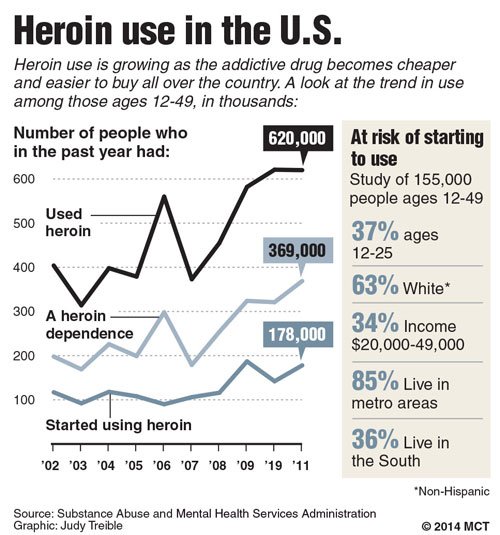

Statistically, one in 10 adults will have drug or alcohol problems in their lives, Andrew Pucher, president and CEO of the National Council on Alcohol and Drug Dependence (NCADD), said.

“Addiction causes a lot of grief,” Pucher said. “If you think of the economic impact — the cost of health care and the impact on the criminal justice system — it’s very expensive to society, both emotionally and financially.”

The election cycle has brought the drug and alcohol epidemic to the forefront of national conversation, but drug abuse and subsequent treatment of people with addictions barely entered the discussion until this year. Nightly broadcasts about new medicine to help people who are overdosing, or about addiction in general, are in abundance, but there is little talk of what comes after an overdose or life after addiction.

That’s where the Oxford Houses and the work of Jason and his students in DePaul’s community psychology program come in. They do research on the effectiveness of the houses — are people finding jobs, how long is the average stay in an Oxford House and, most importantly, are people remaining sober.

Rather than focusing solely on the individual level, the community psychology program focuses on the community and the environment people are in. Jason and his students, who are entrenched in the field of community psychology, used the discipline to understand what people in recovery needed from their communities and themselves in order to be successful. They didn’t wait for people to come to them, but rather went to communities to create a more public health approach to head off addictive behaviors.

“In a sense it’s the fit of the individual and the social context that we want to study, rather than just the individual,” Jason said. “(Through this) we can see how individuals and communities support health, coping and adaptation.”

In terms of their work with the Oxford House organization, Jason and his team thought it was a good idea for people to come up with solutions to their own problems. The first house in the U.S. in 1975 was started by then Sen. Paul Molloy who sought treatment for his alcoholism at a halfway house that would later close due to financial difficulties. Molloy and others took over the lease and renamed it Oxford House after the Oxford Group, the religious organization that influenced the founders of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Today there are nearly 2,000 Oxford Houses around the country.

The purpose of the houses are to ensure people have the tools and support systems to help themselves overcome drug abuse and addiction. The government doesn’t keep track of the number of people who die every year due to drug or alcohol addiction, but the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) found that in 2014 the number of people who overdosed on prescription drugs was just over 25,000, while the number of people who overdosed on heroin was around 11,000.

Jason and those who have worked with him through the program provide empirical data, showing why the houses are important and whether or not they are effective. A lot of people end up in jail or in prison, Jason said, but by broadening the reach of the program and expanding who receives help the hope is to lower the rate of people behind bars.

Research that he and others conducted found that nearly 70 percent of people who went to Oxford Houses were sober two years later, but, if they didn’t go to an Oxford House only 35 percent were. This data helped the Oxford Houses become an empirically validated program, which has helped the organization spread its message and build more houses.

“We try to empower them to get the resources and skills they need to be more successful so we can broaden our reach,” Jason said. “When people come out of jail and prison, the two things they ask for are shelter and a job. Those are the two things our society doesn’t provide them. Oxford House can provide them these things in an inexpensive way because it’s self-run.”

Those who live in Oxford Houses find jobs and do chores around the house to help them begin to move back into the community. In the last year alone, Jason said, 25,000 people have lived in Oxford Houses making it the largest self-help recovery program in the U.S.

Everyone works and puts money and time into their home, making them a step higher than a regular halfway house. This helps people make friends and rebuild their networks, filling them with people who support sobriety and who understands the struggle with sobriety. It’s about changing the social ecology, he said.

The networks aren’t the only facet that must change, Jason said. Old policies, ones that enforce mandatory minimums and don’t allow for progress or inhibit the ability of addicted people to get jobs and get out of their old communities should also be addressed and rectified.

In March, the Obama administration announced actions his administration would take to address opioid abuse and the heroin epidemic. The speech, as well as other actions taken by the president this year, may be connected to the detrimental impact the War on Drugs, the 1971 initiative started by President Nixon, had on largely minority and blighted communities.

In a speech given to the National Prescription Drug Abuse and Heroin Summit in Atlanta, Georgia, the president proposed an increase in patient limits for physicians, more funding for clinics and hospitals who handle patients with addictions and more funding to a select group of states to enhance their medical-assisted treatment programs.

Illinois, among other states, eased its drug policies from 2009 to 2013, but with the current budget stalemate money that might go to recovery programs is frozen. The Oxford Houses, which are self-sustaining, are not immune from the crisis.

Venable, who has been active with the Oxford House community for the past 20 years, hopes it continues and hopes money and other means continues to trickle to the organization so they can continue their work.

“Oxford House works on the premise of family. There are many members who return to the community and get jobs and go on with their lives,” he said. “It helped them — and me get a fresh start after addiction. It’s saved thousands of lives in Illinois alone. That’s the beauty of it.”