Teeming with life from diving penguins to schools of fish, the waters off the coast of Antarctica will now be protected under international law after 24 nations, including the United States, agreed to create the world’s largest marine reserve that spans an area almost as large as Alaska.

The treaty is the first time nations have established a marine reserve together, and is further heralded as a feat for the cooperation displayed between the United States, China and Russia amid economic and political rivalries.

The hotly debated issue of protecting the environment by law is always divided between two sides: those who want to preserve ecosystems, and those that want to further economic interests. Yet after a decade of nations creating some of the world’s largest reserves, it seems that leaders are increasingly favorable in protecting the environment, an effort often led by President Barack Obama’s administration.

“In recent years, numerous marine reserves have been created and have been shown to be successful,” said Tim Sparkes, professor of behavioral ecology at DePaul. “It seems likely that the establishment of the Antarctic marine reserve and the cooperation involved by multiple nations will foster more developments like this in the future.”

In many ways, the Antarctic marine reserve is the apex of over a decade of efforts by nations to create large marine reserves to protect fragile and diverse ecosystems. Usually the reserves are created within a nation’s borders, but now they span across them.

The international body that oversees the waters around Antarctica, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, or CCAMLR, announced the creation of the Antarctic marine reserve on Oct. 28, after years of negotiations.

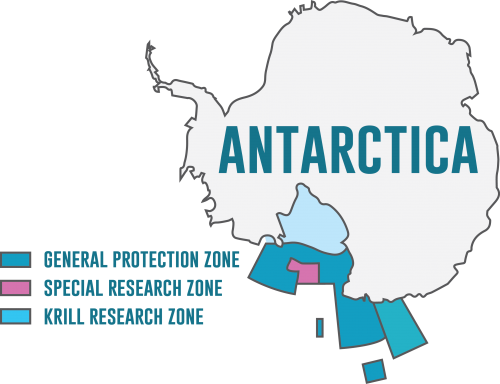

The treaty will go into effect in December 2017 and last for 35 years, banning commercial fishing and mining in roughly 600,000 square miles of the most species-rich waters in the Antarctic Ocean. Only scientists will be able to fish in 28 percent of the reserve, where they can catch a limited number of fish and krill, small shrimp-like crustaceans that are food for the world’s marine ecosystems.

But the road to October’s announcement was anything but smooth. For the past six years, the CCAMLR had been seeking to establish a marine reserve in the Ross Sea, an effort led by New Zealand and the U.S. Many conservationists urged the creation of a reserve for decades.

The Ross Sea is located far from human populations and has so far escaped damage from human enterprises such as heavy fishing, shipping and mining. Because of the high price of fish and low cost of fuel, many fishers as well as miners have been looking to the area as a potential gold mine.

“Commercial fishing and mining operations can potentially cause disruptions to the stability of natural ecosystems,” Sparkes said. “Banning commercial fishing and krill fishing in these areas provides the opportunity (for) there to be stability in natural ecosystems.”

China and Russia opposed the marine reserve at first, which would tamper efforts to feed their nations’ hungry economies.

By 2015, China had come onboard. By 2016, Russia created a government advisor on the environment and greatly expanded its national park system in the Arctic — coinciding with U.S. efforts to do the same in the Pacific Ocean. Amid U.S.-Russian rivalries over hacking in the election and the conflicts in the Ukraine and Syria, the nations were able to arrive at a compromise.

The compromise they came to fell short for many conservationists, but nations that depend on heavy fishing and mining required a short-term treaty, one where they have time to ponder its renewal.

Up until now, the U.S. has created the world’s largest and most successful marine reserves within its own borders. That effort has been characterized by the use of executive authority and by clashing disagreements between conservationists and industrialists. It is also one of bi-partisanship within the nation’s leadership and compromise between rivaling interests — in many ways, reflecting the creation of the Antarctic marine reserve.

In July 2014, the Obama administration announced its most ambitious conservation effort yet: the expansion of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument to 490,000 square miles, six times its original size, across the U.S. Pacific Island territories.

Originally created by former President George W. Bush, the marine reserve now prohibits dumping and mining, and commercial fishing in 65 percent of the area to allow for tuna fishing necessary for the locals’ livelihood. The compromise highlighted the Obama administration’s aim to balance the preservation of marine species, and the economic impact of halting deep-sea fishing.

Obama used executive authority to expand the marine reserve via the Antiquities Act, created by former Republican President Teddy Roosevelt in 1906. Requiring the area to be unique and considered necessary for the protection of future generations, the act was originally made to preserve prehistoric sites in Southwestern U.S. like burial mounds and cliff dwellings.

From the get-go, the Antiquities Act was not used for its intended purpose. Roosevelt employed it to protect landscapes like Mount Olympus in Washington and the Grand Canyon, moves that were opposed by miners who wanted to dig in the mineral-rich areas.

The Pacific Islands reserve was the 12th time Obama used the act to preserve “monuments.” Besides protests from the Pacific fishing industry, some members of Congress opposed the reserve, saying it would negatively impact the economy.

In 2016, Obama moved again. Using his executive authority under the Antiquities Act, Obama quadrupled the size of the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument around the Northwestern Hawaii Islands to about 583,000 square miles. The monument, also created by Bush, now prohibits commercial fishing in the area.

But while many cite the monument as preserving native Hawaiian culture, others say it degrades it because natives can no longer practice their long tradition of fishing.

Following the expansion of the Hawaiian Islands marine reserve, some Republicans at the party convention in Cleveland this year called for revisions of the Antiquities Act. The act provides too much power to the executive branch, they say, and in the hands of a conservation-minded president can unfairly tip the balance against economic interests. Instead, the members of Congress demanded that the creation of monuments requires approval from both Congress and state legislatures.

So far, the Obama administration’s efforts to strengthen marine reserves have increased waters where commercial fishing is prohibited from 3 to 13 percent. Yet all of these efforts have taken place in the Pacific Ocean. According to National Geographic, the 400-year-old fishing industry in New England has barred efforts to prohibit fishing in the Atlantic Ocean, fishing that may be detrimental to marine ecosystems there.

With the creation of the world’s largest marine reserve, and nations’ continued efforts to maintain their own conservations, issues of law enforcement arise. While mining is stoppable because installations are obvious to spot, illegal “pirate” fishing is not.

“Agreements won’t matter if no one is enforcing them,” U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry said in 2014 after the creation of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

About 20 percent of the world’s fish are caught illegally, studies by the Pew Research Center have found. To stop illegal fishing, the Obama administration has proposed a range of methods: improving the transparency of countries’ seafood supply chains, increasing inspections and implementing technology such as sonar and camera buoys that would inform law enforcement where there is “pirate” fishing.

Overfishing, over-mining and other activities that take a toll on ecosystems will continue across the planet for the foreseeable future.

“The ocean as we know today is a product of Earth’s long history,” Kenshu Shimada, professor of paleobiology and biological sciences at DePaul, said. “This new international agreement is indeed a remarkable step to help preserving the marine ecosystem.”

“However,” Shimada said, “because Antarctica’s Ross Sea is just a small portion of the global oceanic mass, protection of organismal diversity on a global scale would also require creating large protected areas in temperate and tropical regions.”