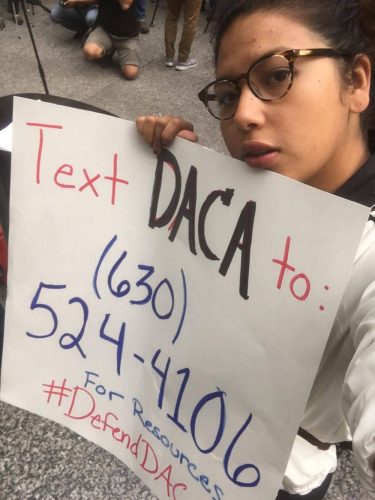

When President Trump announced on Tuesday, Sept. 5 that Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) would be rescinded, sophomore Brenda González decided that she couldn’t stand by as her life became even more threatened than it already is — so she decided to do what she knows best: organize.

DACA, passed via executive order by former president Barack Obama, allows undocumented students who wish to seek higher education and work authorization must apply for DACA. The Trump administration intends to delay the repeal for six months, which means that the future is up in the air for a lot students. This is exactly why González decided to march on Daley Plaza that Tuesday.

“It gives us more exposure, and it gives us more momentum to the undocumented movement right now,” González said. “Being vocal and having the Latinx Students group on Facebook is helpful. What’s missing on this campus is the voice — we have the numbers, but we don’t have the rallies and the actions.”

González said she is going to be focusing on organizing at DePaul for the next year. Her goals include making undocumented students visible and the opportunity to feel safe on campus.

“The past two weeks have really been testing me, but what I’m trying to do is organize an action to show (administration) that we are here,” González said. “I want to be humanized.”

González is just one of DePaul’s unknown number of undocumented students. Because DePaul’s application does not ask for citizenship status, the impact that undocumented students have on the university is virtually impossible to tell.

This does not mean that DePaul’s undocumented student population has been overlooked — last spring, undergraduate students voted yes or no on a Student Government Association (SGA) referendum that would add $2 to the quarterly Student Activity Fee. The referendum, which was introduced by Undocumented Vincentians and Allies (UVA), passed after spring elections. Eventually, each additional $2 per quarter will make out to be $6 per student, and the extra money will go into a pot of money for scholarships for undocumented students.

“I think the hardest part of this process is dealing with organizations that weren’t too welcoming (of the referendum),” said Larissa Aranda, president of UVA. “We had the College Republicans, you know, and everyone has a different opinion and different mentality, but degrading someone’s humanity is not a good thing. No human being is illegal.”

“We were told we weren’t going to have to fear deportation,” Aranda said. “Last week was like another slap in the face. I haven’t even been active in UVA because I don’t even know what to do,” Aranda said. “I cannot tell students that we’re going to be fine if I’m not fine myself.”

Arand said that they are trying to keep an ongoing relationship with SGA, especially president Michael Lynch.

Lynch said that SGA will have an official liaison to work with UVA throughout the year, who will have direct contact to him.

“SGA is going to stay connected with our undocumented student population to hear their needs and concerns,” Lynch said. “We are true partners in all that we do, so whatever they need, we will work together on it.”

Aranda said that although she is hopeful, she does not think the scholarship money will be made available to undocumented students before the 2018-2019 school year.

“That’s definitely not my goal,” said Patricia Santoyo-Marín, associate director of the Office of Multicultural Student Success (OMSS) and liaison to undocumented students. “I’m trying to get that money in student’s accounts as soon as possible. I’m very sensitive to the urgent needs that our undocumented students have.”

Santoyo-Marín is not new to working with undocumented students. She first starting serving undocumented students as an undergrad, where she said she learned about serving people of color and students from low income backgrounds.

“Quickly, we’re learning that there are so many needs and that we have many people throughout DePaul that have been instrumental in getting us to this place,” Santoyo-Marín said. “I do want to acknowledge that joint efforts that throughout the last couple of years have yielded for this opportunity to be institutionalized and have someone here to support students.”

Santoyo-Marín said that she is dedicated to serving undocumented students at DePaul as best she can and that she’d like to continue making resources as equitable as possible, as she has in previous roles.

OMSS’s team also includes graduate assistant, Yessenia Mejia, who has been developing relationships and plans with undocumented students since last year.

Rosita Palma, a junior, was brought over to the U.S. from Mexico when she was five-years-old. She said that when she learned the news of the DACA repeal two weeks ago, that she immediately thought about her younger brother, who is 12-years-old. Unlike the rest of Palma’s family, he was born on American soil.

“Who’s going to take care of my little brother if we all get deported?” Palma asked.

She said that her parents have hope that if they needed to leave the U.S., that they could resettle easily in a different country, but Palma doesn’t think that it would be that easy for her.

“This is where I learned how to ride my bike. This is where I learned everything, even the good and the bad. This is where I’ve lived,” Palma said. “This is all I know and I don’t wanna go anywhere else. This is my home.”

As far as support from the university, Palma said that she feels like DePaul can do better.

(Ally Zacek, The DePaulia)

“I need more than two people,” Palma said. “What can (DePaul) do to make sure we can stay here and continue our education?

I spoke at the Dignity Rally, but I didn’t think that it was enough,” she continued. “On top of everything, I still have to worry about my family and school, but everyone is asking me to organize or educate them or they want to interview me. I am overwhelmed.”

Santoyo-Marín said that her position exists “to really serve our students through opportunities, information and connections” as well as “to serve as a liaison to our colleagues at the institution” to connect students with resources throughout other departments at the university.

“We are establishing a relationship with two other student groups to further engage what they mean when they say they do not feel safe,” Santoyo-Marín said. “We can gage and understand that students might not feel safe, but it is really important that we ask what that means. Is it public safety? Is it speakers on campus?”

“Once we figure out what that looks like, we can start to provide correct information and trainings.”

Palma also said that the DREAM resource guide, which was put together by the Dream Working Group (which Santoyo-Marín said is made up entirely by volunteers), that DePaul provides is very outdated, which only contributed to her skepticism of the university being able to serve its undocumented student population.

Santoyo-Marín said that updating the guide, along with co-chairing the Dream Working Group, is on her to-do list.

“Unfortunately, undocumented student news needs to be updated every day,” Santoyo said. “In the meantime, as an answer to the immediate needs, I’ve decided to take the different information and opportunities and put it in emails to folks like (Mejia).”

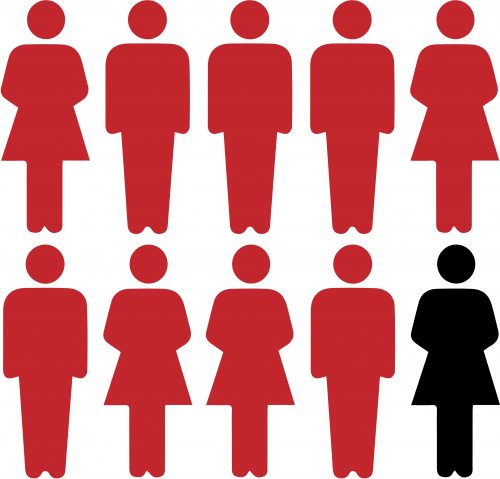

A survey administered in August by the Center for American Progress asked 3,000 DACA recipients about their work status, and nine-tenths of each those polled said that they held a job.

Most immigrants take on jobs as janitors or nannies because they are often unable to apply the skills and degrees they earned in their home country cannot be applied in the U.S. Degrees from foreign universities are often considered invalid.

“There’s people who are biology teachers in Mexico who are taking care of your children or cleaning your kitchens now when they can be working in a laboratory doing research for something important, like medicine,” Palma said. “They’re here cleaning your kitchens because we don’t give them opportunities to do the things they are capable of. My mom is that biology teacher.”

“As a business student, it came to mind that a lot of money that comes into the States was going to be lost,” Aranda said. “We contribute so much to the economy.”

Immigrants pay sales taxes every time they make a purchase and they also pay property taxes. The Center for American Progress estimated in July that over $460 billion in GDP will be lost over the next 10 years, as 700,000 immigrants will lose their jobs without DACA. Immigrants pay into Social Security as well. They don’t reap any of those benefits, contrary to popular belief.

González’s plan is to continue organizing, while at the same time staying on top of her grades and focusing on her mental health. She works with the Pilsen Neighborhood Community Council, where she focuses on advocating for the civil rights of immigrants across Chicago. Undocumented people are not only valuable because they are a part of the American workforce, González said.

“I’m not going to let someone make me a dollar sign, because that’s not what I am,” González said. “I am a story.”