Latest IMF forecast points to slowing global growth, trade tensions

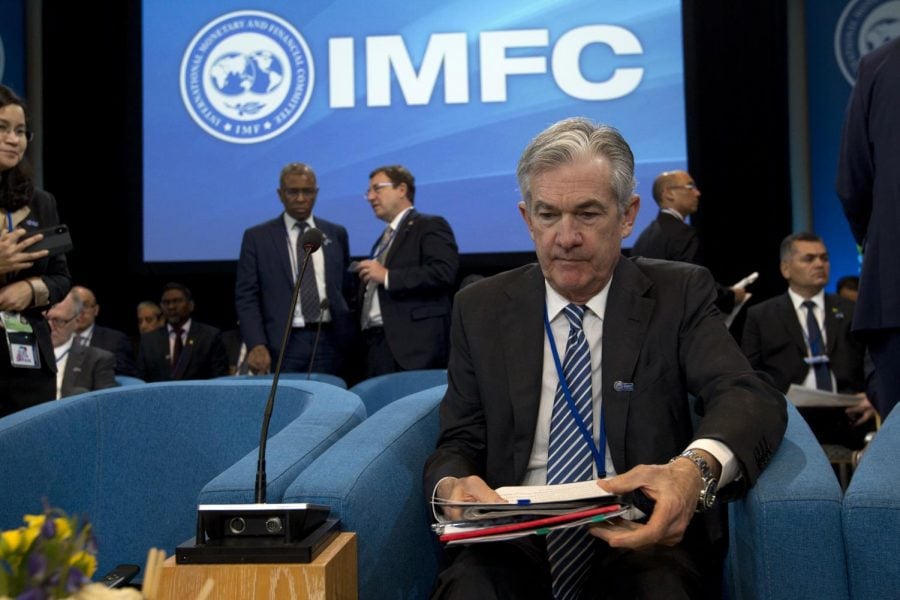

Credit: Jose Luis Magana | Associated Press

Federal Reserve Board Chair Jerome Powell during the International Monetary and Financial Committee meeting, at the World Bank/IMF Spring Meetings in Washington, Saturday, April 13, 2019.

The International Monetary Fund trimmed its forecast for global growth to the lowest level since the financial crisis as ongoing trade tensions and slowing economic growth in advanced economies continue to put a dent in the world economy.

The IMF expects the global economy to grow 3.3 percent in 2019, down from 3.6 percent in 2018, according to its latest World Economic Outlook report issued April 9. This marks the third time in the last six months that the IMF has adjusted its outlook, following strong growth in 2017 and early 2018. In the IMF’s previous forecast in January, it predicted global growth would be 3.5 percent.

Overall, 70 percent of the of the global economy is forecast to decline this year. Advanced economies are projected to expand 1.8 percent in 2019 before plunging to 1.7 percent in 2020. In comparison, emerging markets and developing economies are expected to grow 4.4 percent before growing 4.8 percent in 2020.

Trade tensions between the world’s two biggest economies, the U.S. and China, have increasingly taken a toll on business confidence. Consequently, financial market sentiment has worsened, leaving uncertainty in the international business environment with firms cutting back on foreign trade and investment.

In the U.S., the IMF economists foresee this year’s growth to be at 2.3 percent compared with 2.9 percent in 2018. The IMF cut its outlook for the euro-area economy to 1.3 percent this year, down from 0.3 points in January, with political uncertainty lingering on a potential no-deal Brexit withdrawal of the U.K. from the European Union.

“I think that the IMF is just responding to the realistic situation about the world and how it’s like a domino effect,” said Joanna Bauza, president and CEO at The Cervantes Group, a project-based international technology service company headquartered in San Juan, Puerto Rico. “They’re trying to be realistic and they’re hoping that things are going to work out to a positive way, but they can’t really predict how countries are going to be reacting with their current situations.”

The Commerce Department on Wednesday, April 17, reported that the U.S. trade deficit with China dropped to an 8-month low in February, as imports from China plunged 20.2 percent while U.S. exports to China increased 18.2 percent. The U.S. deficit on trade in goods and services narrowed 3.4 percent to $49.4 billion, which is the lowest level since June 2018.

“The trade disputes have direct consequences, impacting global trade—now growing at a slower pace—and global manufacturing,” said Karim Pakravan, an adjunct economics professor at DePaul who previously worked for years in the international banking industry. “Indirectly, they affect business confidence by creating an uncertain environment and disrupting the logistics chains.”

The IMF expects growth in international trade to increase 3.4 percent in 2019, a slowdown from its January estimate of 4 percent and from 3.8 percent trade growth last year.

This comes alongside IMF economists expecting the global economy to pick up in the second half of the year, leaving its 2020 forecast unchanged at 3.6 percent predicated on a rebound in Turkey, Argentina and other emerging markets.

“Most of the growth in the world economy in recent years has come from emerging markets,” said Animesh Ghoshal, a professor emeritus of economics at DePaul. “They account for about half the world output, and as a whole have been growing twice as fast as advanced economies. So, a slowdown in emerging economies will clearly have a detrimental effect on world growth.”

The current forecast envisages that global growth is going to level off in the first half of 2019 before ticking upward in the second half of this year. Conditions might ease, with the U.S. Federal Reserve signaling a more accommodative monetary policy stance and not expecting to raise interest rates.