OPINION: Executive Orders are necessary against the backdrop of a polarized Congress

Credit: AP

President-elect Joe Biden speaks during an event to announce his choice of retired Army Gen. Lloyd Austin to be secretary of defense, at The Queen theater in Wilmington, Del., Wednesday, Dec. 9, 2020. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

Despite his best efforts to tout “progress,” President Joe Biden is still reminiscent of past eras of American politics in which promises of social change are over-promised and under-served.

With a gridlocked Congress, Biden now faces the difficulty of following through on the policy change he has promised throughout his campaign while attempting to unite ever-growing divisions between the two parties.

At any other time, Biden’s election into the presidency would be just that: business as usual. Except, it’s not just any other time. As a nation, we are just coming out of the Trump presidency –– a presidency that revealed a growing far-right extremist movement and has made many more fervently question the foundations of American democracy.

We have also witnessed one of the most tumultuous years in our nation’s history: the never-ending Covid-19 pandemic, a racial reckoning and a climate crisis that seems to only be getting worse.

After the events of the past year, Americans seem to be expecting more from their politicians, and it has become more and more frustrating that they seem unable to deliver.

In the four years of Trump, the expectation has been a continuation of oppression. The hope for any remnant of progress has diminished as Trump has continued to push anti-immigration rhetoric, criminalize Black and Brown Americans and enforce the American standard of “the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer”. Politicians who do want reform, namely Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, are bound by the restrictions of a divided political system and are then unable to deliver on such promises.

The shift from Trump’s administration to Biden’s, however, represents a possibility for actual progress. Progress that has seemed hopeless for the last four years.

This expectation has largely been placed on presidents. As presidents have expanded their own authority through the history of the United States, constituents have increasingly held them accountable. An article published by Harvard Law discusses this expansion of power, specifically drawing on the fact that the framers never intended for the executive to hold as much power as it does today. The way executive power has expanded is beyond the speculation of the framers due to the vastness of changing times and the emergence of the United States as a global power.

For instance, the framers were not keen on the idea of presidents conversing directly with the people. The rise of media communication and, of course, social media was unforeseen by the founders.

“I don’t think FDR could’ve had the power he did if he didn’t have the ability to do his radio chats, and Trump wouldn’t be president if it weren’t for Twitter and his ability to reach tens of millions of people directly,” Harvard Law professor Michael Klarman said in the Harvard Law bulletin.

Craig Sautter, a faculty member at DePaul with experience in campaigns for political candidates, said that the expansion of presidential authority through the Obama and Trump administrations seems to be reminiscent of the “Imperial Presidency” of the Nixon era.

“Executive orders are constitutional, but seem anti-democratic since Congress should be the one passing legislation and the president signing bills to get things done,” Sautter said, though he added that this is a generalization.

If a president is facing a fierce gridlock in Congress, though, turning to executive orders to push policy forward is necessary for a president to show that they are trying to follow through on campaign promises.

“Basically, presidents have resorted to executive orders just to operate government. And so, you know, it’s a pragmatic solution to a really big problem which is our dysfunctional system with polarized political parties,” said DePaul political science professor Wayne Steger.

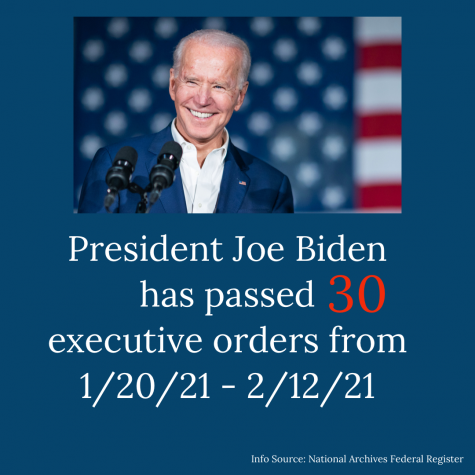

Trump passed 220 executive orders, according to the American Presidency Project. The former president’s executive orders, crafted in a way that displayed his public speaking style often were coupled with first-person preambles that touted his administration’s actions in office but lacked a sense of policy expertise.

Steger said that was a large reason as to why so many of them failed.

“One of Trump’s enormous problems was that he had all these outsiders, and they didn’t know the law, they didn’t know the policy, and so they would write things up that sounded good,” Steger said. “That would be fitting for a press release, but they didn’t work, legally, as governing documents so it just did not withstand scrutiny.”

In Biden’s first weeks in office, he has revoked 31 of Trump’s executive orders, predominantly aimed at the former president’s more controversial policies including his initiative to build a border wall and the creation of the 1776 Commission report.

Biden’s actions in the first few weeks to revoke Trump administration policies are absolutely necessary. Not only does this send a message that the Biden administration wants to mend the harm caused by the Trump administration, but it shows a sentiment of progress.

Ben Epstein, a political science professor at DePaul, says that since Biden has formulated much of his campaign against Trump’s most controversial executive orders but it is important for his public image to follow through.

“So, not only is it him following up on campaign promises, which is what, you know, what politicians are often wanting to do,” Epstein said. “They’re things that Trump didn’t actively try to create as policy.”

It is difficult to achieve longevity in policymaking, especially since a future president could also reverse orders that didn’t fit their political agenda. Epstein says that the major policy that Biden is pushing, such as the Covid-19 relief bill, could help him gain political power if it is believed to help a large majority of people.

“I think Biden is banking on the idea that he is going to create a lot of major changes and major help for millions of Americans, and doing that he’s going to gain major political power in trying to push for policy changes moving forward,” Epstein said.

The issuance of executive orders does not necessarily mean that it will become law, but Biden’s actions to revoke Trump’s executive orders is a promising first step for the “progress” he hopes to achieve. The difficulty remains in uniting a divided Congress and continuing to push forward necessary reform that is greatly needed.