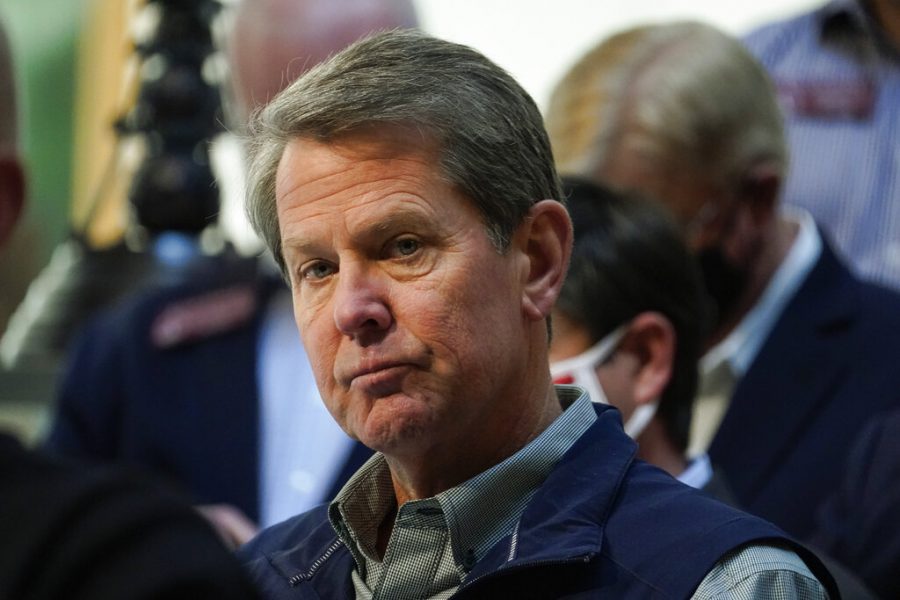

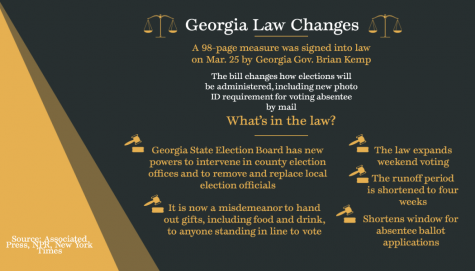

On March 25, Republican Gov. Brian Kemp passed a law that rewrites Georgia election rules. The legislation, one of many proposals across the country to pass similar laws, follows a contentious election season in which false claims of voter fraud sparked growing fear in Republican-led legislatures.

Georgia was at the center of the debate on election integrity in the 2020 election. After Democrats successfully flipped the state for the first time since 1992 and the runoff elections that followed elected two Georgia Democrats to the Senate, former President Donald Trump led a growing uproar by the Republican Party that the elections were fraudulent. Legislation proposed throughout the country to rewrite election rules is largely a direct reaction to this, and the Georgia election law is the prime example.

Christina Rivers, a political science professor at DePaul who specializes in voting rights, says that though the legislation is not direct voter disenfranchisement, it is reminiscent of the Jim Crow era.

“The point that I’m trying to make is some of the dimensions, the details, of this legislation are pulled out of the old Jim Crow playbook,” Rivers said.

One of the most concerning aspects of the legislation, Rivers added, is that it makes it easier for the state to cut down the number of voting precincts.

According to a New York Times analysis of the law, if a voter goes to the wrong polling place, they will now have to travel to the correct polling site in order for their vote to still be counted. Georgia had already closed more than 214 voting precincts around the state from 2012 to 2018, according to an investigation by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. This provision in the law would make it even harder for voters to make it to the right precinct, creating a larger risk for disenfranchisement.

Rivers continued to say that these aspects of the law would not have been possible with a provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that has since been stricken down.

“Now that that provision was stricken down by the Court in 2013, it makes it really easy for states to pass these types of harmful election laws because there’s nobody to check,” Rivers added.

The 2013 Supreme Court ruling eliminated an essential part of the Voting Rights Act, allowing nine states to change their election law without federal approval. The nine states affected in this law, including Georgia, can now pass legislation that would not be possible otherwise. If not for that Supreme Court ruling, the recent law in Georgia would likely not have been possible.

There are many other provisions in the Georgia election law that are concerning to voters and critics of the legislation. The law also imposes strict voter ID requirements, narrows the time to request absentee ballots, allows the Republican-led legislature to have more power over the Georgia State Election Board and makes it a misdemeanor to offer food and water to voters in line.

Erica Knox, a policy advocate for the Chicago Lawyers’ Committee, is on the Voting Rights Team for the organization. The team is working to prevent, reduce and eliminate barriers to voting for all eligible voters, particularly for communities of color and low-income residents in Illinois.

As proposed legislation across the country aims to revise election laws, Knox said the team is monitoring bills that are being introduced and seeing if they get any traction.

“And really, what we’re seeing is legislators who want to turn back the clock on who can vote in this country and many are using that myth of widespread voter fraud to do it,” Knox said.

Knox said that, as they continue to survey what is happening with election laws in high-profile states such as Georgia, the team continues to see the work done by pro-voter advocates and organizers to prevent further disenfranchisement.

“And so we’re keeping an eye on that and understanding that we may need to do the same one day to protect our democracy here in Chicago, Illinois as well,” Knox added.

At the same time, as more than 250 bills have been introduced by Republicans to restrict voting, Democrats are pushing for a law that would include a massive expansion of voting rights at the federal level. The bill, called the For the People Act, would end partisan gerrymandering, constrict the influence of money in politics and would expand early and mail-in voting.

The legislation has been passed in the House, but will now have to endure a Senate filibuster. Tensions over the filibuster continue to rise and now take on a new level of urgency after the Georgia election law was passed.

The filibuster’s history is embedded in that of the Jim Crow era, as it was often used to block Civil Rights legislation in the 1960s. Now, with the increased sense of urgency felt by Democrats to block continuing proposals from Republican-led legislatures to restrict voting, the issue of the filibuster has become more pressing. The pending For the People Act could undo the legislation in Georgia, but will likely not pass under current Senate rules.

Wayne Steger, a political science professor at DePaul, said that he doubts that voting rights would lead to the abolishment of the filibuster, but that the parties are waging a symbolic fight over democracy.

“Voting is a big deal because if the Republicans do this in enough states, they’ll deny Democrats the ability to win in elections,” Steger said. “So it’s a fight over the rules because the definition of the rules define who can play the game and who can win.”