By the end of the 2012 elections, Democrats were riding a momentous wave. President Barack Obama won re-election by a fair margin. Democrats won seven of the 11 governor seats up for grabs. Although Republicans retained House control, Democrats gained two seats in the Senate to slightly widen their hold there.

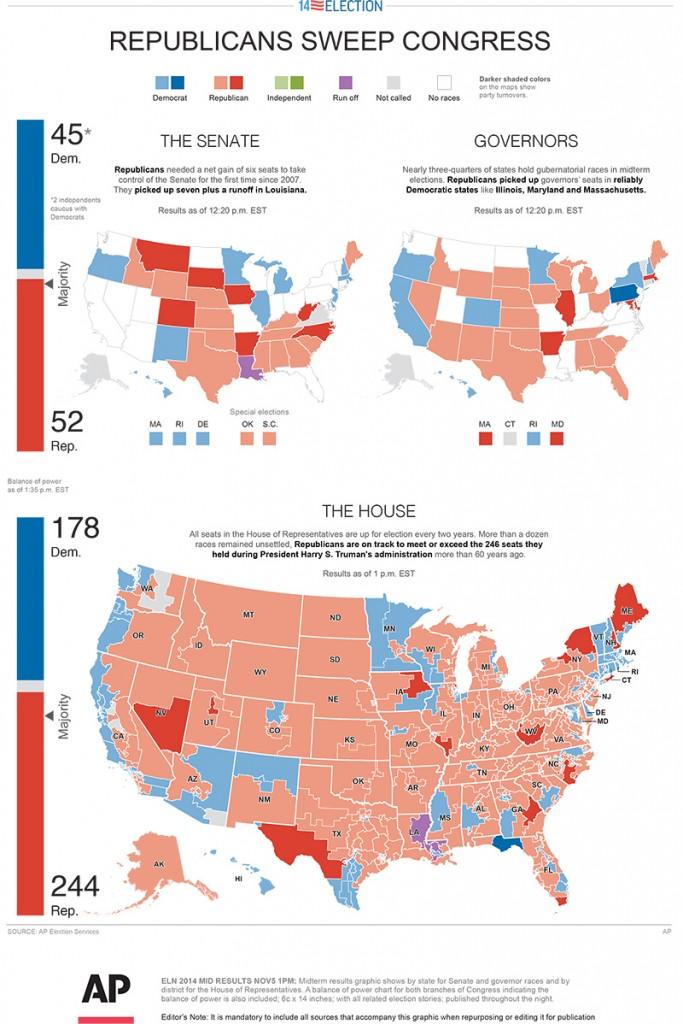

Flash forward to Nov. 4 2014. Riding a nationwide wave of anti-Obama rhetoric and Democrat fatigue among voters, the GOP found overwhelming success in close races. Republicans claimed governorships in Democrat strongholds. The GOP House majority widened to one of its largest advantages ever. And Republicans finally claimed the once-elusive Senate majority needed to control Congress.

This last aspect has perhaps the farthest-reaching policy consequences. Gridlock had already been adamant in the last few years of the Obama administration, as the Democrat-majority Senate was repeatedly used to block House legislation that Democrats found unpalatable.

Now this buffer is gone, and dynamics will certainly change. Throughout Obama’s last few years, he will likely face numerous pieces of legislation that run counter to his goals. He will then have to sign or veto any bill that comes across his desk. Pundits are wondering what common ground will exist between Obama and the new Congress, especially in a polarized political climate.

“Both sides of the aisle have strong polarizing factions, but on some issues they’ll eventually have to compromise,” Nicholas Kachiroubas, a visiting DePaul public service professor versed in the field of the presidential administration, said. “If they give in to polarizing factions all the time they’ll never get anything done, and you have to wonder how much the public will willingly take.”

Because of the checks and balances between the two branches of government, there is likely to be an interesting negotiating dynamic between the two parties when it comes to passing legislation.

“Congress could choose to repeal, say, Obamacare. Of course, Obama would veto the repeal, but Congress has the full budget authority to defund many parts of the program,” Kachiroubas said. “Much of the future jockeying will likely revolve around the budget books. What may happen is that Congress will say, ‘We’ll fund these parts of your programs if you preserve these pieces of legislation without veto.’”

Of course, there is also the possibility that extreme gridlock would prevent any major legislation from being passed until the next presidency. In that case, some of the onus would shift toward executive order, which encompasses the set of law-backed actions that the president could take without Congressional approval.

No provisions in the U.S. Constitution explicitly govern executive orders; however, Supreme Court decisions over the years have established that such actions can only help to administer and facilitate existing legislation, not create them. This is subject to wide interpretation, as well as wide potential for lawsuit if Congress believes these actions overstep their bounds.

“Historically, the president has always (used executive powers) more often with a divided Congress,” Kachiroubas said. “However, the president doesn’t have the unilateral right to do whatever he wants.”

So far, Obama has enacted 193 executive orders versus 291 for George W. Bush and 364 for Bill Clinton. An example of a notable Obama executive order included ordering the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to conduct gun violence research, which falls under his right to direct a federal administration to conduct previously mandated research.

It’s important to remember, however, that executive order is not as sweeping as bipartisan creation of legislation. With the new political climate, one may only speculate as to how this will occur.

“People do get irritated by division, but it’s important to remember that this is historically common and that unified government often doesn’t exist,” Kachiroubas said. “While gridlock does slow things down, legislation that does make it through will have gone through negotiations and may involve multiple perspectives. The result could possibly be a better end product.”

“The question, of course, is how long gridlock will happen, and for what issues people in Washington will be willing to cooperate on,” Kachiroubas said.

A look at various policy fronts

Tuition Reform

This remains a serious issue, as the Federal Reserve Bank of New York reported that nearly 39 million borrowers continue to carry more than $1 trillion of federal student debt.

A few policies have been passed on this front. For instance, in 2012 the Obama administration was able to pass the Pay As You Earn program to cap loan payments at 10 percent of certain debtors’ monthly income, and executive order earlier this year extended the program to an additional five million borrowers.

Additionally, in August 2013, Obama announced a plan to establish a federal ratings system for universities. Federal funding for schools will then eventually be tied to how schools rank, in an effort to get colleges to spend more efficiently. However, little progress has been made since on this front, as funding changes require bipartisan legislation. It remains to be seen what executive orders or legislation, if any, will be announced in the near future.

Immigration Reform

Immigration has been a hot button issue over the past year. Animosity from Latino constituents has surrounded failed efforts to pass the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act (DREAM), which would provide permanent residency to certain criteria meeting immigrants who arrived as children and studied here or served in the military. Considering that impactful legislation stalled even with Senate support, this is a likely realm for Obama to act unilaterally with executive power.

“I would act in the absence (of a congressional solution),” Obama said Nov. 5, “And take whatever lawful actions that I can take that I believe will improve the function of our immigration system.”

In 2012 his administration authorized Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which protected some migrants who would qualify for DREAM from prosecution. Similar efforts may ensue: Vox Media predicted that deferred deportation might be expanded to protect certain groups, such as migrants with children. However, barring bipartisan legislation, it will be impossible to expand the possibility of citizenship for undocumented migrants.

“I don’t know of any precise measures or proposed bills out there, not even from (Florida Republican Senator) Marco Rubio,” Elizabeth Martinez, director of DePaul’s Center for Latino Research, said.

Obamacare

Doomsday conspirators need not fret. As Kachiroubas previously said, Obama can veto attempts to completely dismantle the Affordable Care Act, and the Republican Congressional majority does not encompass a two-thirds majority needed to override a veto.

What’s more likely is Congress will chip away at portions of Obamacare. There are certain Obamacare aspects that Democrats don’t support: Illinois Senator Dick Durbin expressed willingness in 2013 to repeal the Medical Device Tax, which taxes equipment providers to provide revenue for insurance costs. This could be early on the chopping block as Democrat support could give the numbers needed to override aveto on portions of Obamacare.

Furthermore, political ramifications of Obamacare may go beyond policy implementations. Sarah Kliff from The Washington Post reported, “The vote share of Democrats who supported health care reform was 5.8 points lower than that of comparable Democrats who opposed the bill.” Forcing Obama to veto Obamacare repeals, although accomplishing nothing in policy, could be a symbolic gesture that garners Republican support for 2016.