South Side activists work to improve vaccination rate

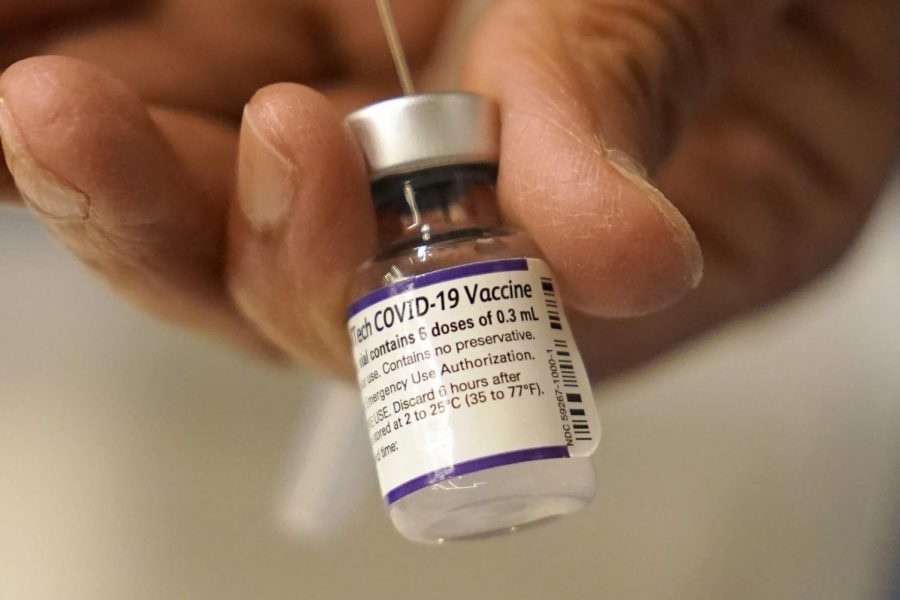

AP Photo/Steven Senne, File for The DePaulia

Dr. Manjul Shukla transfers Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine into a syringe, Thursday, Dec. 2, 2021, at a mobile vaccination clinic in Worcester, Mass. Pfizer said Wednesday, Dec. 8, 2021, that a booster dose of its COVID-19 vaccine may protect against the new omicron variant even though the initial two doses appear significantly less effective.

In an effort to counter low vaccination rates in South Shore, Ernest Sanders, executive director at South Shore Works, sent a team of “street wellness fellows” to distribute masks and hand sanitizers to community members in South Shore every day. The fellows also shared their own, unscripted experience with the vaccine to neighbors.

“That free gift is a way to get people to listen to you and to open up,” Sanders said.

Sanders and his team at South Shore Works distributed around 38,000 masks and hand sanitizers, he said. But it didn’t seem to make a difference.

“I thought I was making progress, and then quickly you just find out you are not,” Sanders said. “We were once ranked the community with the highest number of [Covid-19] fatalities back in April of 2020, and just yesterday, I was aware of our rate rising again at about 13 percent.”

Not only does the South Shore community have some of the lowest vaccination rates in Chicago, but it also has some of the highest fatality rates. City data shows prevalent disparities: Black people are consistently dying from Covid-19 at a higher rate than any other population in the city.

Despite South Shore Works’ efforts to bring the vaccine to the community and dispel misinformation, only about 49 percent of the community has completed the vaccine series, according to Sanders.

“49 percent is a big difference from about 63 percent, so I have my work cut out for me,” Sanders said, referring to the city’s then-overall vaccination rate.

As of Sunday, the zip codes in Chicago with the lowest vaccination rates are all on the South and West Sides of the city in primarily Black and Latino neighborhoods.

Only 65.5 percent of the current population is fully vaccinated, according to city data as of last week.

One of the reasons many minority communities in Chicago have the lowest vaccination rates is the lack of accessibility and a plague of misinformation surrounding the vaccine controversy, according to Oscar Sanchez, the director of youth and restorative justice programming at Alliance of the Southeast (ASE).

“It stems from inaccessibility to true care from people in the medical profession, inaccessibility to information about the pandemic and even then, inaccessibility to vaccines,” Sanchez said.

In addition to lack of accessibility to the vaccine, Latino communities are battling generations of distrust and fear of the system, he said.

“It’s the reality of having to navigate insurance, having to navigate who is paying for it, having to navigate hospitals and authority figures because they’re undocumented and scared of being deported,” Sanchez said. “Parents then passed down that generational trauma and fear into their children, which makes sense because they want to protect their families, but now they’re not getting the proper treatment.”

Despite facing struggles with being undocumented or lacking health insurance, the threat of misinformation is prevalent.

“I got vaccinated recently,” said South Side resident Jesus Sanchez. “But I’ve heard that others don’t want to get vaccinated because they’re afraid of being injected with a disease that may come out in the future.”

The city has been struggling to overcome systematic racial inequities for years. With the help of coalitions like ASE, it has begun combating misinformation and accessibility issues surrounding the vaccine in minority communities.

To increase racial equity in the vaccine distribution in Chicago, Mayor Lori Lightfoot implemented the Protect Chicago Plus Program, where canvassing teams went door-to-door to encourage residents in 15 targeted communities with the lowest vaccination rates to get vaccinated against Covid-19. This program aimed to dispel misinformation about the vaccine and educate residents on where, how and why they should get vaccinated, but left out under-vaccinated minority communities like South Shore, which still has some of the lowest vaccination rates in Chicago despite the city’s efforts.

Regardless, nonprofits like South Shore Works are actively trying to bring more vaccines to South Side communities that the city has neglected during vaccine distribution.

Even though South Shore was not included in the initial program, South Shore Works was able to expand the initiative themselves with their own team of community volunteers.

“I’m trying everything under the sun to bring our vaccine numbers up, but if I don’t have people’s trust, then my work is really in vain,” Sanders said.

Lightfoot’s vaccination mandate that went into effect on Jan. 3 does not account for gaps based on race and location in less-vaccinated communities.

The mandate requires every person aged five or older to provide proof of vaccination and a valid government-issued ID if older than 16 when entering bars, gyms, restaurants or entertainment venues where food and drink is served.

City officials hope the new mandate’s added restrictions from restaurants, bars and other indoor facilities will motivate the city’s youths to get vaccinated. However, there is still controversy regarding whether this mandate will be effective and if it will unintentionally dissuade unvaccinated Black and Latino Chicagoans from receiving services or seeking employment.

Even though the mandate may have unintended consequences, “we absolutely support barriers because our health depends on it,” Freeman-Wilson said.

Sanchez considers the mandate necessary, to an extent. However, he believes a more efficient way of increasing vaccination rates in South Side communities is for the city to hire local community doctors to talk to residents and explain the importance of the vaccine, dispelling much of the present concern.

“You have to have people from the community talking about the vaccine, people they recognize, so it’s not just Dr. [Chicago Department of Public Health Commissioner Allison] Arwady,” Sanchez said. “Who says she has my best interests? When other organizations have said she is approving things we don’t agree with.”