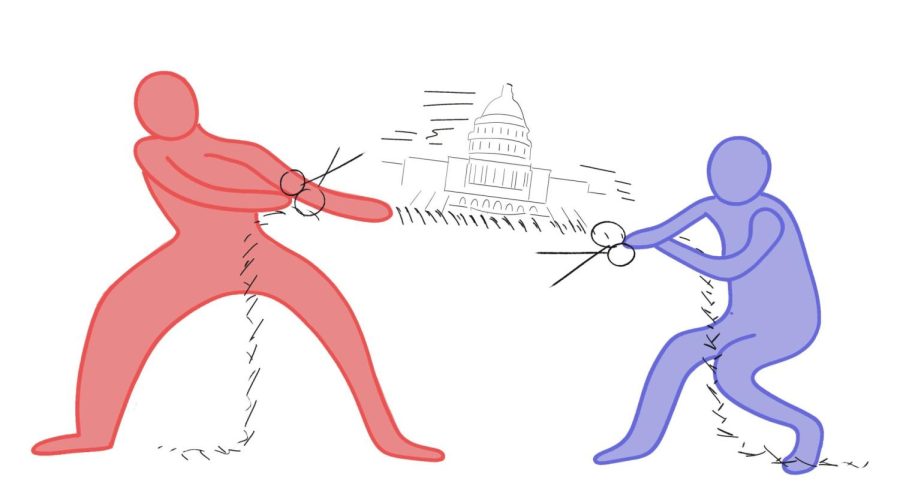

Meddling in the midterms: How partisan influence in U.S elections chip away at democracy

Gerrymandering: it’s as American as apple pie.

As the United States nears the 2022 midterm elections, politicians and analysts alike have once again advanced concerns over gerrymandering efforts across both state and party lines, raising the alarm of partisan attempts to interfere with democratic processes.

Since the U.S. Supreme Court first ruled in 1964 that both congressional and state legislative electoral districts states have to contain near-equal populations, district lines have been redrawn every 10 years following the release of the U.S. census to meet this requirement. And since then, state legislators have attempted to use redistricting to benefit their political party.

Thus far, the 2020 redistricting cycle has been no different.

Across the country, majority parties in state legislatures utilize two gerrymandering tactics: “packing” and “cracking.” Legislators “pack” the opposing party’s likely voters into a few small districts in order to eliminate them from other district elections, and “crack” them by spreading the opposing party’s likely voters across several districts to dilute their influence. By using both of these methods, majority parties attempt to manufacture positive results come Election Day.

“Instead of the voters electing their representatives, the representatives are picking their voters in a manner that ensures that the vast majority of the seats up for grabs are predetermined,” said Sheldon Jacobson, a computer science professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Because most state legislative houses have been controlled by Republicans in recent years, the Republican Party has had more opportunities over the past two decades to gerrymander: Texas and North Carolina in particular have been widely accused of creating unfair district lines in their respective states.

However, the Democratic Party is not innocent of gerrymandering, either: Illinois and Maryland, both holding Democratic majorities in their state legislatures, have also come under fire for gerrymandering their district maps.

In Illinois, Democratic Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed the state’s new congressional map into law Nov. 23, 2021. Drawn by the state’s Democratic-majority legislature, the map has received an “F” rating from the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, a project dedicated to nonpartisan analysis of district remapping, and has faced significant criticism over alleged gerrymandering.

“The voters of Illinois should be frustrated,” Jacobson said, “because they really have very little choice. It’s a predetermined election already. Just look at the district that snakes through the urban areas downstate, and you realize that this was done with pure intent to capture as many Democrat voters and to dilute the Republicans along the interstate highways going between Peoria, Bloomington and Champaign. They want to grab as many of the left-leaning voters to ensure that they can capture an extra district.”

The practice of gerrymandering in the U.S. is by no means new — in 1789, Founding Father and former Virginia Gov. Patrick Henry redrew his state’s electoral districts in an attempt to keep his rival James Madison out of the very first U.S. Congress.

However, recent technological advancements have allowed mapmakers to up the ante, creating more precise and sophisticated gerrymanders than ever before in American history.

“All of that gerrymandering from Patrick Henry in the 1790s all the way through the 2000s is the minor leagues,” said journalist and author David Daley, “And in 2010, it leaps into its steroids era.”

Beginning with REDMAP, a project initiated that year by Republican strategists that utilized new technologies to create computer-generated district maps that favored Republican candidates, both major political parties began making use of increasingly elaborate redistricting processes in attempts to negate the other party’s redistricting gains.

Gerrymandering isn’t the only way state legislatures are influencing elections, though — last year alone, at least 19 states have passed 34 laws restricting access to voting, and over 440 similar bills have been introduced in 49 states, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

Since former president Donald Trump used false claims of electoral fraud in an attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 election, Republican legislators have made use of similar rhetoric to reduce ballot access under the claim of election integrity protections.

In states like Ohio and Texas, Republican-led governments will only allow one ballot drop-off box for every county in their respective states during the coming elections.

“You think about a place like Harris County — which contains Houston — and you’re talking about millions of people in that county, and one drop box?” said John McGlennon, government professor at the College of William and Mary and former Democratic congressional candidate. “That’s just totally useless.”

In March, Georgia made it illegal to hand out water or snacks to people standing in line to vote.

And across several states, Republican lawmakers have attempted to increase partisan control over electoral oversight by limiting the powers of secretaries of state, governors and anyone not viewed as loyal to the G.O.P.

There’s one major problem with these alleged attempts to protect against widespread electoral fraud, though: there’s no evidence of widespread electoral fraud.

Critics have argued that these measures have been imposed with the intent to suppress votes to the benefit of Republican candidates.

“These laws are solutions to problems that don’t exist that end up creating very real problems of their own, which tend to resonate to the advantage of the Republican Party,” Daley said.

While partisan efforts to influence elections continue, many have been challenged and even struck down.

In Ohio, a successful 2018 ballot measure to reform the state’s redistricting process has twice resulted in the state’s Supreme Court to reject disproportionately drawn legislative maps. Michigan passed a similar ballot measure that same year. And on Nov. 4, 2021, the Department of Justice sued the state of Texas, claiming its restrictions on mail-in ballots and voter assistance risked disenfranchising the disabled, elderly and non-English speaking voters.

Still, many ongoing efforts to shift the electoral process in favor of states’ respective majority parties remain unchecked.

“There are ways in which individual states can take action to limit the manipulation of the electoral process,” McGlennon said. “There are other ways in which it really takes national legislation to address these issues. I think there’s likely to be some nibbling around the edges of efforts to manipulate or suppress votes, but with the current division in Congress, it’s hard to see a very comprehensive national effort succeeding.”

Jim • Feb 28, 2022 at 11:12 pm

Mr Jacobson shows his liberal bias in his writing! Way to go Dr. !