As commuters descend the steps to the Jackson Red Line stop on a weekday afternoon, they will likely notice a group of five or six people in yellow vests standing in the middle of the platform. Although riders might observe handcuffs and radios on their belts, these guards are not police officers.

They are private security with the same training and authority as guards employed at many suburban shopping malls.

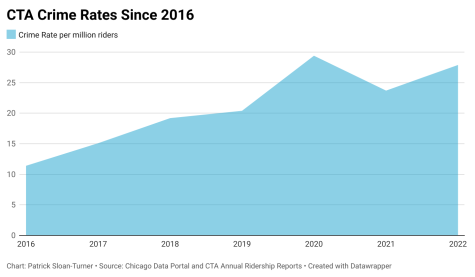

During the first quarter of 2022, CTA violent crimes like assault, battery and robbery took place at a higher rate than any year in the past two decades, alongside theft too, according to the Chicago Data Portal. In response, the Chicago Police Department (CPD), the CTA and Mayor Lori Lightfoot contracted two private security firms to bring in guards to help curb crime.

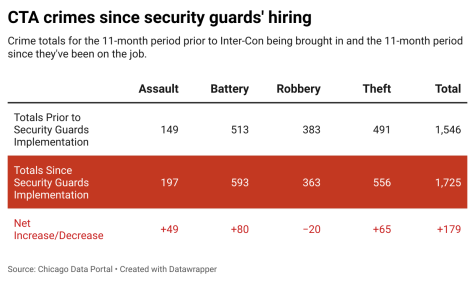

The contract, with a price tag of $71 million, allowed for the hiring of 300 officers between the two firms of Inter-Con Security Service and Monterrey Security Consultants. Now, nearly one year later, data shows the city’s strategy has done little to make transit safer. Instead, crimes on CTA trains, stations and platforms have increased by a significant margin.

Assault, battery, robbery and theft went up by an aggregate of 10.4% on CTA compared to the same period a year prior to the guards’ hiring, according to the Chicago Data Portal.

Figures from the same dataset reveal that instances of battery alone increased by 15.6%, validating riders who feel the guards have not made things safer.

“[The city] has talked a lot about putting in more security at stops like Jackson and Chicago and State and several downtown stops,” said Thomas Flynn, a Lakeview East resident and regular CTA rider. “But every time I’m there, I just see a group of [officers] huddled together not really doing their job.”

If increased rider safety was the goal when bringing on these officers, Flynn believes the city missed the mark and said he finds them less than attentive.

“They should be looking at the train, they should be monitoring the staircases and the turnstiles, but they’re not doing any of that really,” Flynn said.

Like other major cities, staff shortages plague the CPD. Instead, these unarmed guards are tasked with the safety of Chicago’s transit but have less training and tools than police.

To become a security guard at Inter-Con or Monterrey, applicants must pass a drug screening, a background check and prove they can meet certain physical requirements like standing for an entire shift.

Monterrey is the same company that employs on-campus security at DePaul’s campuses.

Both company’s guards must hold a state-issued guard license, according to the Inter-Con’s job postings. Obtaining one of these licenses requires passing a 20-hour class, offered by several companies online, and costs around $60.

Experts like Leonard Sipes, a retired federal public affairs specialist, believes policing safety on an entity as vast as the CTA requires specific training and tools that unarmed guards do not have in most cases. Sipes, who previously served with the Department of Justice’s clearing house for Crime Prevention and Security, said these guards are trained to do something entirely different than police are.

“Ordinarily, private security exists solely as some sort of warning that if something happens, there is an individual there who will contact law enforcement,” Sipes said. “In most cases, they have no authority, have no training and they have no arrest powers.”

CTA did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story, but in March 2022, they explained the role of its security guards in a statement announcing the guards deployment.

“Security guards are a visible presence that can be a deterrent to improper behaviors on trains and buses, and in stations,” the statement said.

The same statement went on to say guards will enforce “CTA’s Rules of conduct which prohibits activity such as smoking…among other behaviors.”

Last month, Ald. Brendan Reilly (42nd) quote-tweeted a video showing one of CTA’s own guards smoking on the Jackson Red Line platform.

While Sipes understands the idea of a uniformed presence deterring criminal activity, he believes these instances can be complicated. He said that cases often involve perpetrators under the influence of substances or dealing with mental health issues, making it a tough situation for security to handle.

“That [guard’s] role is usually going to be nothing more than contacting law enforcement and providing a description of the assailant,” Sipes said. “If you want to steal somebody’s purse, if you want to do a smash and grab, there’s really nothing a private security officer can do.”

Previously, the CTA had its own dedicated police force, but it disbanded in 1979, according to CBS Chicago.

One Monterrey officer working security on a CTA platform in the Loop last month told The DePaulia their job indeed usually consists of calling in law enforcement in dangerous situations.

“If someone [is] being loud or aggressive or something we [are] supposed to call the cops,” said the officer, who requested anonymity. “It’s not any type of hard job, it’s just long days of just standing down here.”

Of the 478 CTA crimes reported through January and February 2023, CPD made an arrest just 199 times, according to figures from the city’s data portal. This period shows a 37% increase in CTA crime from a year ago, before the city announced the hiring of the guards.

Flynn said he has seen all kinds of incidents in transit, even witnessing a robbery at the Jackson stop, a stop with one of the highest crime rates in the city, and feels crime is a regular occurrence. Since the increased presence of security on platforms, Flynn said he has not felt any safer.

“It just seems like there’s a lot of action going on at these stations,” Flynn said. “[The guard’s] job is to kind of monitor [activity] and you know, monitor if someone’s smoking on the platform, if someone’s screaming about something, they’ve got to be more attentive to these issues.”

Although riders might rather have increased officers patrolling CTA instead of unarmed guards, that might be out of the question. CPD saw a decrease of more than 3,000 officers since 2019, according to figures obtained by The DePaulia in a Freedom of Information Act request (FOIA).

While Chicago may not have the officers to patrol the CTA right now, Sipes believes the key to future safety is not just actual police presence on CTA trains, stations and platforms, it is instituting non-traditional police practices.

“Hundreds of studies financed by the U.S. Department of Justice that looked at proactive policing endeavors…indicate that it does reduce crime,” Sipes said. “In fact, nothing else even comes close to it.”

As explained on Sipes’ own website, proactive policing refers to the practice of regular patrols and community engagement, rather than the traditional practice of responding to calls. In the CTA’s case, this means officers whose sole beat would be a CTA station or platform.

Other cities with major transit like CTA have police units dedicated to patrolling transit systems. New York City, Washington D.C. and Boston are all examples of cities with dedicated transit units, all of which reported less violent crimes per rail rider in 2022 than Chicago, according to analysis of each city’s crime data.

Because of nationwide police staffing shortages, Sipes said that private security firms like Inter-Con and Monterrey are in high demand. With two years left on the CTA’s three-year contract to deploy these guards, crime will need to drop significantly to justify the $71 million in taxpayers’ dollars spent.

“It hasn’t seemed like that investment is really worth it,” Flynn said. “These security guards aren’t really able to do much besides…[calling] the police, and it’s not really worth that high dollar amount.”

Mario / Apr 3, 2023 at 1:02 am

I ride the train everyday, how are they a deterent when they are all in one car sitting or standing