“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” George Santayana once said. Never before is this saying so true, as events of the present often hark back to those of the past. This awareness can help us understand how present-day things came to be, and how patterns of the past may recur in the future.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” George Santayana once said. Never before is this saying so true, as events of the present often hark back to those of the past. This awareness can help us understand how present-day things came to be, and how patterns of the past may recur in the future.

But the quick-witted will insist that these events could have hardly developed in a single day. This is an important point, for dates reveal a particular instance of a larger historical process, akin to reading a single page of a broader book. With this in mind, let us open ourselves to the past and see what occurred on this week in history.

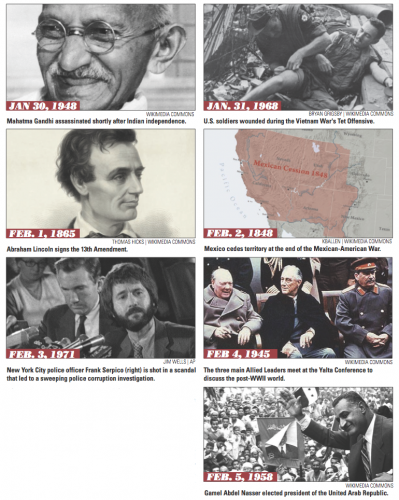

If one thinks of non-violent demonstration, two figures come to mind: Martin Luther King Jr. and his predecessor and inspiration, Mahatma Gandhi. Although remembered as the leader of the Indian independence movement, on Jan. 30, 1948, Gandhi was shot during a prayer session with his family and followers. The killer was Nathuram Godse, an Indian from New Delhi who, dissatisfied with Gandhi’s favorable demeanor toward Indian Muslims, assassinated Gandhi with three shots to the chest. But let us not remember Gandhi’s death, but his tireless effort to bring independence to his people by the use of non-violence.

Over 5,000 kilometers to the east and 20 years later, violence ensued as the Vietcong, a North Vietnamese military and political organization, began its attack on the U.S. Embassy in Saigon on Jan. 31, 1968. During the early morning of that day, 19 Vietcong sappers captured the Embassy and held it for six hours until they were routed by U.S. paratrooper reinforcements. The attack was a part of a larger North Vietnamese campaign known as the “Tet Offensive,” whose objective was to raise a South Vietnamese uprising and turn American public opinion against U.S. involvement in the war. By September 1968 the U.S. and South Vietnamese had held and retaken most of the lost ground, but the Tet Offensive successfully inflicted heavy American casualties that led to massive protests back in the U.S.

As with foreign policy, the American public has notoriously been divided on domestic social issues as well. Perhaps most famously was the issue of African American enslavement. On Feb. 1, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln signed the 13th Amendment, officially abolishing slavery. Two years earlier in 1863 the Emancipation Proclamation declared slaves free, but the decision was unconstitutional. By the beginning of 1865 the Confederacy was clearly losing the Civil War, and many northern politicians desired a constitutional amendment that would abolish slavery in all states.

Importantly enough however, African-American inequality continued in America, especially during the “separate but equal” policies of the Jim Crow Era. The issue of racial inequality continues today as the continuing Ferguson and police violence protests demonstrated.

About 20 years before the American Civil War, the United States and the Republic of Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadeloupe Hidalgo on Feb. 2, 1848, marking the end of the Mexican-American War following the U.S. capture of Mexico City. Its terms declared that the Rio Grande would be the boundary of Texas, for Mexico to cede California and a territory containing present-day New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah and parts of Wyoming and Colorado to the U.S., all for the payment of $15 million by the U.S. to Mexico, among other details of the treaty.

For Mexicans who suddenly found themselves within a foreign country, over 90 percent decided to stay and gain U.S. citizenship rather than moving within the new boundaries of Mexico. The Mexican-American War is often stated as a product of manifest destiny, which was a belief that Americans were destined to expand from the Atlantic to the Pacific ocean. Some believe that this tradition of American expansionism has continued to this day.

In New York City on Feb. 3, 1971, NYPD Officer Frank Serpico and three other officers planned to stalk and then bust a local heroin dealer. Serpico walked into the apartment building with his pistol drawn, expecting the other officers to follow in support. By the time he reached the suspect’s door, Serpico looked back but found that the other officers had remained outside. Serpico was then shot by an unknown assailant, and when his comrades failed to call in his injury or support, an elderly neighbor called an ambulance and Serpico survived.

This incident unleashed a controversial debate on police corruption. The argument was that Serpico’s fellow officers had connections with the drug dealers and perhaps while profiting from a cut, decided to remain outside the apartment so that Serpico and their dubious connection would not be revealed. No evidence was found to convict the other three officers. Regardless of their intentions, it again remains that issues of police corruption and violence have not disappeared.

Issues of politics and violence haven’t disappeared either. Nearing the end of World War II, the leaders of the Allied alliance — President Franklin Delano Roosevelt of the United States, Prime Minister Winston Churchill of the United Kingdom, and General Secretary Joseph Stalin of the USSR — met near Yalta, Crimea Feb. 4, 1945, in order to discuss the post-war reestablishment of nations and their borders following the expected collapse of Nazi Germany. After seven days of compromising, the leaders decided on the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany (no guarantees promised for the defeated party); the division of Germany into U.S., U.K., USSR and French spheres of influence; the demilitarization and “denazification” of Germany; the payment of reparations (to cover the cost of damage) by Germany; the creation of a democratic Polish state; the capture and trial of Nazi war criminals; and the inclusion of the U.S., UK, USSR (and later France and China) in the newly created United Nations Permanent Security Council. All of these developments (except in Poland, where mock democracy reigned) went through and helped create the Europe that we know today.

But not all state boundary changes in the 20th century have occurred in Europe. Fourteen years after the Yalta conference and across the Mediterranean Sea, Egyptian President Gamel Abdel Nasser became President of the newly formed United Arab Republic (UAR) on Feb. 5, 1958. This was a political union between Egypt and Syria from 1958 through 1961.

In 1958, as Syrian Communists threatened to take control of Syria, the ruling Ba’ath leaders decided the only option to preserve their power was to form a political union with Egypt. Nasser agreed with the union, as he had been trying to bring his Pan-Arab nationalist dream to reality. But the union did not go as planned, as there were discrepancies on how to rule two countries with one political system, and in 1961 Syrian military officers staged a coup in Syria and broke off the union with Egypt. While Pan-Arabism did not necessarily die out with the UAR, it was Nasser’s last successful attempt at bringing his dream to reality. At present Pan-Arabism seems even further from feasible reality, as the continuing regional conflict unfortunately shows.