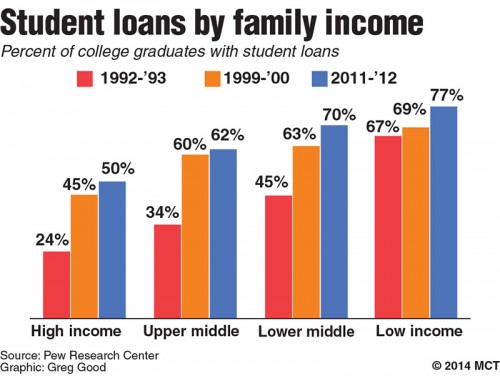

The student loan crisis is one many students are all too familiar with, as the daunting question “how will I pay back my loans?” looms over the collegiate experience as students go further into debt every academic year.

The question may already have an answer, though it isn’t well known yet. Income-Based Repayment plans, or IBRs, are a way for students to pay back their federal loans in a way that correlates payment amounts to the income of the borrower, reducing the anxiety of repayment.

The plan’s most recent changes cap payments to 10-15 percent of disposable income, rather than a fixed monthly payment that could have been as high as 20-25 percent of disposable income, which may help to solve the crisis for in-debt students and ease the possibility of properly paying off loans.

A 2007 law brought about IBRs; repayment terms were more generous, monthly payments were capped at 15 percent of income and the living expense deduction was raised significantly. By including more students into the IBR plan, those who earn less pay less and won’t have to worry about default if they can’t pay.

“This is a brilliant idea. It’s the second optimistic move I’ve seen that is helpful for all people,” John Berdell, DePaul professor of economics, said. “Most Americans have limited means to insure against unforeseen problems like sickness or losing income and tying these payments reduces the risk that adverse conflicts will hurt us.”

Former President Bill Clinton created a new loan option in the 1990s, adapting the initial plan from the 1960s that allowed students to borrow directly from the Department of Education and be eligible for an income-based repayment plan. Payments were limited to 20 percent and any balance not repaid was forgiven after 25 years. The 2007 implementation of IBRs only further aided indebted students.

Shelley Mesch, a junior transfer student studying journalism, has $70,000 in combined debt, which includes a Parent PLUS loan. She likes and supports IBRs, given that repayment is a worry many college students face.

“Growing up it’s understood that not a lot of people can really pay for college,” Mesch said. “Everyone goes in debt, but (a degree) is something you have to have to go on to get a good starting job.”

Plans in other countries, like Australia, factor in the idea that not everyone gets to make it to college. The country adds a supplemental tax onto the incomes of those who go to university, according to Berdell.

“We’re doing something similar to that with this program,” Berdell said, referencing Australia’s plan. “Australia’s system is much more attractive to those making these big decisions and for those who may be first generation college students and are afraid of debt. Our plan shows that people of limited means no longer have to be limited by the borrowing program or the debt they incur.”

As a solution to the debt crisis, not enough is known about whether or not the plan will be successful for all students, but it is a step in the right direction. Making higher education more public — like what President Obama recently proposed to do with community college — as well as paying attention to the inequality gap, were all recommended ideas.

“It’s not an immediate solution, but it is something worth pursuing,” Mesch said. “Capping repayments would decrease the amount of anxiety our generation faces. This could help society get over the idea that repaying (loans) is worth more than college itself.”