Humans are accustomed to hearing about foreign, bloody wars with dangerous consequences. This is especially true for Americans, whose soldiers are stationed on bases across the globe, whose majority of troops just recently left long conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. But these conflicts across the Middle East, Europe and Africa have changed since then. What has been missed?

Most have heard of the Islamic State since its capture of Iraq’s second largest city of Mosul and the route of the Iraqi military in 2014. Also known as ISIS, or ISIL, the self-proclaimed Sunni caliphate controls large portions of both Iraq and its neighbor Syria. Perhaps after it left al-Qaeda, and after its ruthless killings and persecution of anyone trying to stand in their way, the Islamic State’s policy has been to attack and absorb any neighboring country, and in doing so the terrorist organization is now seen as violent and unpredictable by much of the world. Supported by U.S. trainers and Iran’s Quds force — an interesting concert to say the least — the Iraqi military has made repeated attempts to regain lost territory, but the effort has been unsuccessful thus far.

Although much of the Islamic State’s territory lays in Iraq, the other portion and its capital al-Raqqa reside in Syria. In 2011, during the Arab Spring protests that swept the Middle East, many Syrians voiced their desire for political inclusion in a government controlled by President Bashir al-Assad and his Alawite cohorts. Al-Assad refused their demands and instead began suppressing the opposition with military force, who in return organized themselves into armed groups. “Basically you have a ruling government whose answer to popular discontent is brutality,” said Kaveh Ehsani, professor of international studies at DePaul. “You have an opposition that has become problematic, that claims to be democratic but is not.” Other factions rose waving flags of their own religious ideologies, such as al-Nusra Front, which is known for being as brutal as the Islamic State. As such the lines between the many factions are hard to define.

Outside powers soon began to support those who shared similar objectives. The Syrian government receives aid from Iran, and Russia, which has a naval base in the country. Various opposition groups are supported by the U.S.—those deemed democratic—and by regional powers such as Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Qatar. “Instead of trying to disarm the region,” said Ehsani, “we are fueling it.” According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, over 330,000 people died from the war as of August and millions fled to safer places such as Europe, creating new controversies concerning what countries should take refugees and in what number. While the United Nations attempted a peace accord in 2014, peace in Syria is not within sight.

On the other side of the Middle East is Afghanistan, which many great powers have invaded and in turn have been defeated. Three years after the death of Osama bin-Laden, the U.S. military officially concluded its combat operations in Afghanistan, leaving a small contingent of soldiers in the country who are due to leave in 2016. Now, the Taliban is again encroaching from old refugee camps in eastern Pakistan in an effort to retake Afghanistan. The U.S.-trained Afghan military has struggled to hold its ground, and questions remain unanswered whether the Afghani government can survive without U.S. or NATO help.

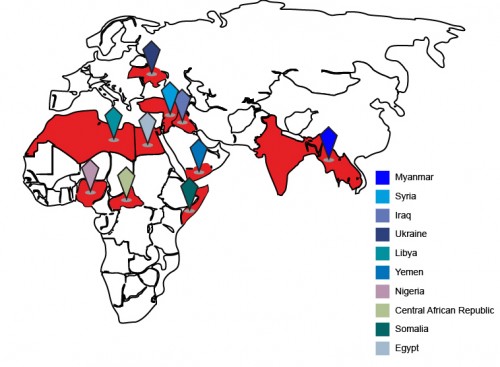

There were 19.5 million refugees at the end of 2014.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

Following major defeats in Afghanistan, al-Qaeda raised training camps and bases in Yemen, the country located on the south-west tip of the Arabian Peninsula and a the historic crossroads between Africa, the Middle East and the Indian Ocean. During the same Arab Spring upheavals that affected Syria, Yemen’s President Saleh stepped down in face of Yemeni protests in 2012. The new President Hadi set his sights on defeating al-Qaeda in Yemen, but in 2014 the Houthis, who adhere to the Zaydi sect of Shia Islam, rose in arms to obtain more political power and captured the capital of Sanaa. President Hadi fled the country to neighboring Saudi Arabia while the Houthis occupied northwestern Yemen. In response, Saudi Arabia and a collection of allies began bombing the Houthis in an attempt to place President Hadi back in power. Iran, Saudi Arabia’s regional rival, aids the Houthis in military support. Yet again, neither side has agreed to any peace agreement.

In western Africa, the continent’s most populous country and one ravaged by war, Nigeria, saw the rise of a militant group called Boko Haram that began attacking government and UN buildings in the country in an attempt to impose its version of Islam. In 2014, five years after they began their takeover, Boko Haram pledged its allegiance to the Islamic State; whether they actually aid each other is up to further investigation. The Nigerian government has allied with neighboring countries of Chad, Cameroon and Niger who are also threatened by Boko Haram. So far the alliance has failed to dislodge Boko Haram.

These are only a portion of the many conflicts burning across the globe. In Mexico drug cartels battle the government and the United States; in Ukraine a flimsy cease-fire keeps the peace between Ukraine and the Russian-backed Donetsk and Luhansk republics. There are many interstate conflicts, civil wars that are fueled by leaders seeking power. Notable conflicts of this caliber, including Sudan, South Sudan and Myanmar to name a few, are spurred on by religious and ethnic differences.

Richard Farkas, professor of political science at DePaul, attributed most of the violence to “the splintering effect,” or self-determination. According to Farkas, many leaders call minorities and marginalized peoples through emotional, nationalist appeal to create a country for one people. However, these leaders and their aroused peoples often forget a simple consequence: small state, small economy. “What will they produce?” asked Farkas. “How are they going to attract investment?”

“One thing all these conflicts have in common is that the majority of the dead are civilians,” said Robert Garfield, professor of history at DePaul. “This has been common since World War II.” Garfield said that there have been no conventional wars, the kind where modern armies fight face to face, because formal war is “frowned upon” since the two world wars. “Another reason is that modern warfare is hideously expensive,” said Garfield. “If you can obtain your objective by killing a lot of civilians, you save yourself a lot of money.”

So instead of using conventional wars to carry out political aims or to conquer regions, great and small powers alike create or use groups to carry out the fight, and supply them with the necessary cash and arms. This is the case in Syria and Iraq, in Yemen, in Ukraine and elsewhere. Because many of these conflicts have continued for some time, and peace accords failed to bring sides to the table, there is good reason to assume that these conflicts will continue. As Farkas said, if learning about these conflicts and how humans are lured into fighting one another, perhaps this will help the U.S. know when others are trying to do the same to us, and in the end, try to stop future conflicts from happening. But then again, humanity doesn’t have such a good track record in regards to peace.

Visitor / Sep 25, 2015 at 9:38 am

While interesting article, it definitely shows only a partial picture. A major conflict in South Sudan has been completely left out. The crisis in South Sudan has been fueling regional refugee crises.