Last week The DePaulia touched upon the topic of elected school boards, one of the many referendum issues that Chicago’s citizens voted “yes” during the recent mayoral election. Another of the referendum questions that was overwhelmingly approved by voters advocated for campaign funding reform in the city of Chicago, an issue whose importance is highlighted not only by the unfairness of elections both here and elsewhere, but by the complex effects of campaign reform policies that have already been discussed or enacted.

Last week The DePaulia touched upon the topic of elected school boards, one of the many referendum issues that Chicago’s citizens voted “yes” during the recent mayoral election. Another of the referendum questions that was overwhelmingly approved by voters advocated for campaign funding reform in the city of Chicago, an issue whose importance is highlighted not only by the unfairness of elections both here and elsewhere, but by the complex effects of campaign reform policies that have already been discussed or enacted.

Chicago’s referendum specifically proposed a public funding system for campaigns, whereby taxpayer money would be used to “match” small campaign contributions from individual donors. The policy intended to reduce the influence that large donors hold over political candidates. Additionally, it would potentially boost victory chances for small-time candidates that lack the large-donor connections and fundraising power of Chicago’s more established politicians.

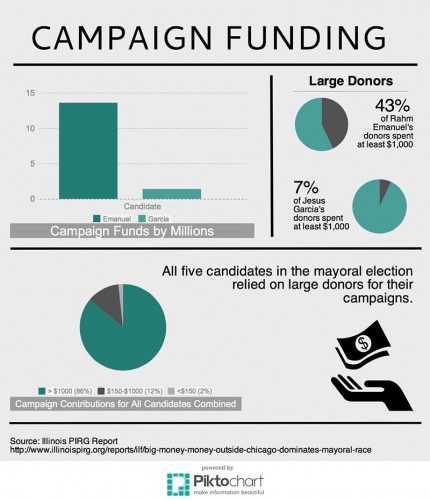

Few elections expressed the potential need for campaign reform better than Chicago’s election. The Illinois Public Interest Research Group reported that 43 percent of Mayor Emanuel’s donors contributed large donations of at least $1,000 to his campaign, which raised $13.6 million total. By contrast, only seven percent of top opponent Jesus “Chuy” Garcia’s donors were “large” donors, and his campaign only raised $1.4 million overall.

Although Garcia succeeded enough to earn approximately 34 percent of the vote and force a runoff election later in April (Emanuel received 45 percent of the vote, short of the 51 percent majority required for an immediate win in Illinois), electoral issues remain prevalent when the incumbent is able to raise more than nine-and-a-half times the amount of funds as the next closest candidate.

Furthermore, a 2012 report from the University of Illinois at Chicago showed that the Illinois Northern District — which contains Chicago — far and away has the most public corruption convictions out of any judicial district in the nation. Thus, much of voters’ approval of the referendum likely stems from their disgust over Chicago’s history of crony politics.

However, “campaign reform” can potentially entail a number of policy actions. With examination of the larger issue, it remains unclear whether the specific proposals of Chicago’s referendum would magically push the city much further toward fairer elections.

Perhaps the most comparable campaign funding system exists in New York City. A series of reforms legally implemented in 2004 has provided $6 in taxpayer money for every dollar a candidate raises from a “small” donor. This effect stacks up until a donor provides $175, at which point it is no longer considered a “small” donation.

New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice found that this system widely broadened the demographic base of campaign donors and candidates for office. Far more minority citizens have since participated in the campaigning process, and the system increased the participation and potential impact of local community groups in comparison to that of large, special-interest donors.

However, there was not necessarily a large effect on final electoral outcomes. The Citizens’ Union of the City of New York found that incumbent city council members were still re-elected at a 95 percent rate during their most recent elections in 2013.

Furthermore, corruption still remained possible under such a system. Former NYC city council member Sheldon Leffler was convicted for a scheme to break up a single $10,000 contribution into smaller, publicly matchable donations.

Chicago’s voters have clearly stated they are tired of machine politics. However, considering the effects of NYC’s analogous campaign system, would election outcomes necessarily change here?

“Politically, perhaps Emanuel’s least popular action was the closing of (nearly 200) schools (in 2013). Despite the massive ad spending, his campaign did not effectively address this issue,” Bruce Evensen, professor of journalism and a former communications advisor to the Clinton Administration staff, said. “He could’ve connected (Illinois’) budget crisis to the school closings. However, instead of looking voters in the eye and saying ‘we have to swallow hard budgeting,’ all he did in his expensive ads was look slick.”

In essence, a large war chest may still not be enough to completely surmount a poor campaign strategy, a history of unpopular policies, or an opponent well versed in making do with less. Fundraising disparity in politics may be heinous, but it is not necessarily the primary determinant of victors in an election — or the primary indicator of corruption.

Whether the funding reform proposal ever becomes officially established remains in question. As with all other recent Chicago referenda, this is a non-binding referendum that requires lawmakers to eventually grant the force of law. As lawmakers deliberate over the issue in the upcoming months, the hope is that they will consider not only their own self-interest, but all potential angles and effects of the proposed policy.

“Do I think money in politics is a problem? Yes,” Evensen said. “Is there any magic solution? No.”

41st Ward Blog • Mar 9, 2015 at 7:27 am

Great article. Enjoyed reading about the benefits of long overdue publically financed campaigns in Chicago and the comparisons to NYC. What are the chances of genuine legislation being passed? Are there any lawmakers willing to sponsor legislation? What will be next steps? And lastly, what can voters do to push lawmakers to pass legislation (are there any specific coalitions working on the issue)? Thanks