The anger that lead to last year’s sexual assault protests and rallies seems to be simmering now in conversations at campuses around the country, as students begin to work with administrations to understand the extent of the problem and make efforts to solve it.

The push for change, and even an acknowledgement of the problem, began with students and they continue to be a major force behind it, both on campus and in the city. The push continues this month in commemoration of Sexual Assault Awareness Month.

Colleges seem to understand they’re not handling the situation well — if at all — and students have played an integral part in the shift of policies and dialogue even though their place in the conversation has come under scrutiny.

“Students are a critical and necessary part of the conversation. They hold the answers to what is needed, what is being done and what isn’t,” Michelle Cahill, a DePaul junior and survivor, said. “I think that students should at least be invited to the conversation. Administrators can establish a base of students who are responsible and experienced.”

Cahill, who has attended summits and a community activist for sexual assault prevention and the approach to solving the problem, sees the importance of student involvement in bringing students into the conversation as activists.

The goal is to begin restructuring the response to sexual assault, as well as to branch out and create better policies for sexual assault prevention not just here, but at universities around the country. Columbia University implemented a new “sexual respect” education program. Last month, UIC hosted a panel sponsored by Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan.

“I think any administration would do well to treat it as you would any significant issue on campus to not only reform this culture that creates justifications for these incidences,” Tyler Solorio, former SGA member and current member of the Illinois Board of Higher Education, said. “The administration needs to be seen, more than anything, as an unwavering supporter that responds swiftly and appropriately. It’s a conversation the administration needs to have and I feel like it hasn’t, at least not with the appropriate student populations.”

“I think any administration would do well to treat it as you would any significant issue on campus to not only reform this culture that creates justifications for these incidences,” Tyler Solorio, former SGA member and current member of the Illinois Board of Higher Education, said. “The administration needs to be seen, more than anything, as an unwavering supporter that responds swiftly and appropriately. It’s a conversation the administration needs to have and I feel like it hasn’t, at least not with the appropriate student populations.”

Though many are doing good work and exposing the multiple facets of the problem, the role students now play has come under question, too. The response to that criticism has been more protests — like those at Columbia after the announcement of the new program — and a shift in action to address spaces outside of the campus bubble.

Cahill and Solorio are both working to create legislation for sexual assault legislation. The work Cahill is doing would allow college students to be more active in supporting students who have experienced assault.

“As students, we should control the discussion about what impacts us, and what should be done,” Solorio said. “Not only is it immoral to create policy without the input of those it directly affects, but it is ineffective as well.”

For change to happen there needs to be a joint effort, and the dedication of administrators to the cause could also be better, according to Cahill and Solorio, as well as around campus. Administrators should establish dialogue with their students and be open to criticism, according to Cahill, instead of being silent partners in the conversation.

“Administrators can establish a base of students who are responsible and experienced,” Cahill said. “These students can help lead programs that are beneficial to the student community in terms of helping survivors and helping promote prevention through ongoing consent campaigns and awareness.”

Anonymous Columbia University Victim • Apr 20, 2015 at 7:51 am

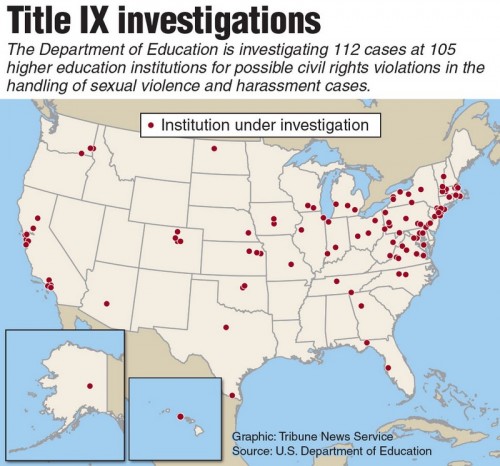

What hasn’t been addressed enough is that several of the Title IX related sex assault and harassment cases are a result of assaults and harassment committed not by other students but by, at least as far as Columbia University is concerned, members of faculty, heads of institutes and departments. In fact most if not all complaints filed by graduate students are against professors, heads of departments, heads of institutes. That distinction is important especially because it seems to influence what sort of retaliation – administrative and/or physical – is meted out against complainants.