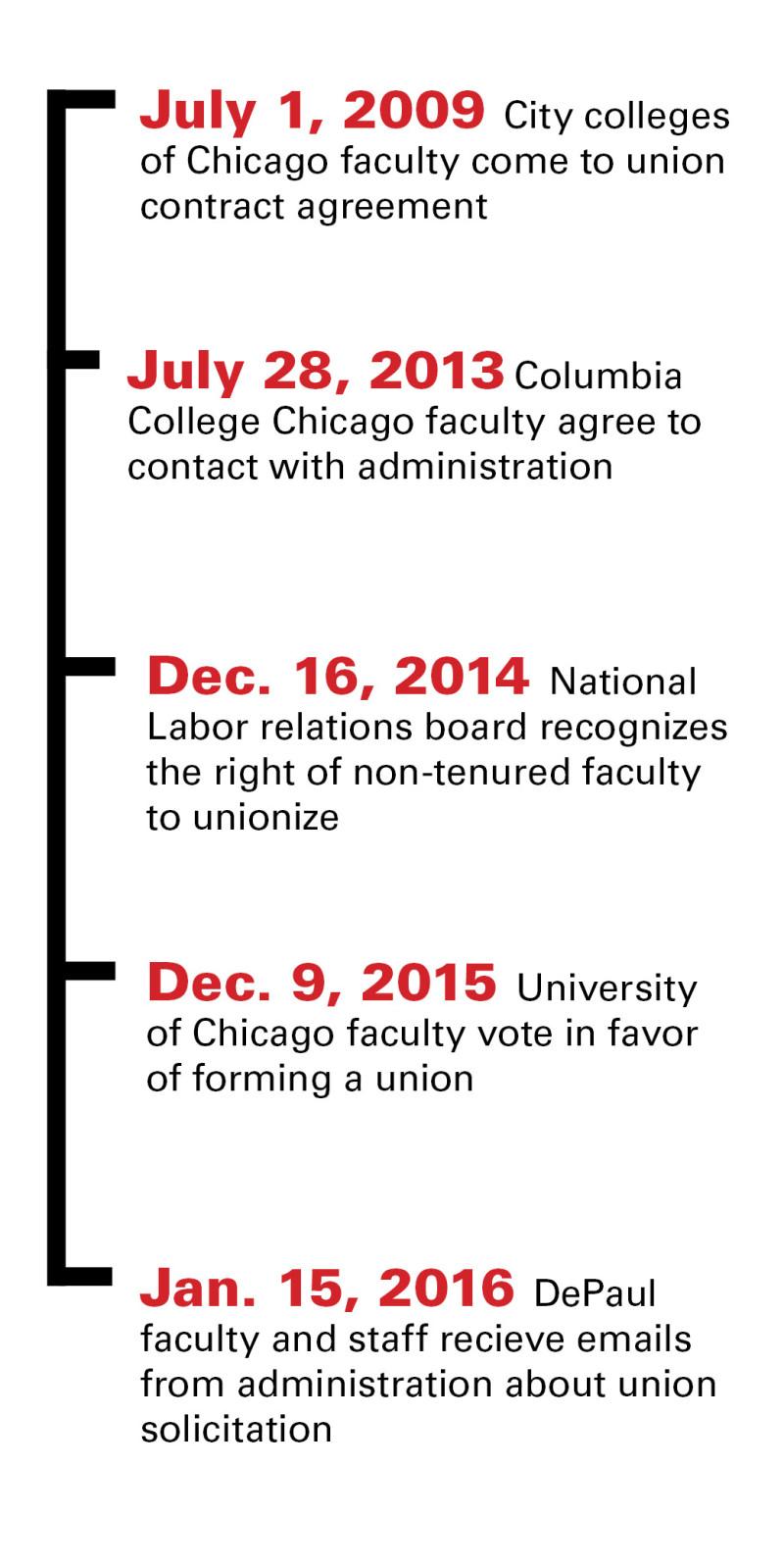

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]otivated by low wages, flimsy benefits and a 2014 precedent-setting ruling by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), adjunct faculty members are rushing to unionize at institutions across the country. Recent momentum at local schools has brought the movement to DePaul, possibly forcing the issue to a head soon.

Unionization efforts have hit religious and secular schools alike; Columbia College, Roosevelt University and UIC’s adjuncts have already been unionized, and the University of Chicago’s non-tenure track faculty voted to organize in October. And with the results of an authorization vote by Loyola’s adjuncts to come down as early as this week, making inroads at DePaul would be a next logical step.

The issue became prominent two weeks ago after Rev. Dennis Holtschneider, C.M. and Provost Marten denBoer sent emails to faculty and staff about “union solicitation at DePaul.”

Both said that while they respect faculty’s right to choose who represents them, they would prefer to maintain a direct relationship.

DePaul currently employs 925 full-time professors and 1,900 adjunct faculty, according to its adjunct fact sheet.

“Our preference is to maintain a direct working relationship with adjunct faculty — without interference from a third party that has no connection or commitment to DePaul and its students, and that may not understand our culture and our values,” Holtschneider said in the email.

Holtschneider also said the union organizer who approached adjuncts was affiliated with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), something the union has confirmed.

“There has been a group of faculty from DePaul involved in the Faculty Forward Chicago campaign since the inception of the campaign more than a year ago,” said SEIU Local 73 spokesman Adam Rosen.

Rosen added that these faculty members have since “had conversations with many full-time and part-time faculty in regards to forming a union” and “are currently building a strong committee of support on campus.”

The issue stems larger than just unionizing faculty. In a separate interview with The DePaulia, Holtschneider said allowing faculty to unionize under the current NLRB standard would mean that the NLRB has certain jurisdiction over parts of a religious institution that are not religious.

This, Holtschneider said, would blur the boundaries of church and state because a state entity would be able to determine which parts of the religious institution are under their jurisdiction. It would disregard religious institutions’ First Amendment rights, he said.

Law School professor Steven Greenberger said that under the current state of the law, “adjunct faculty do have the right to organize, even at (religiously) affiliated higher education institutions, so long as they are not involved in religious activities, which would be principally teaching religious lessons.”

Holtschneider said the university would appeal the NLRB’s jurisdiction standard to the courts, not merely to oppose unions, but to maintain independence as a complete religious institution, not one divided into religious and nonreligious parts.

The issue concerns not just DePaul, but other religious universities as well. Greenberger said that with the continued wave of unionization efforts, it is likely a religious university will take the issue to court.

A university spokesman at Loyola University in Chicago said its administration is still considering whether it will appeal the vote to unionize by their faculty in the College of Arts and Sciences, according to the Chicago Tribune. Ballots from that vote will be counted starting on Wednesday.

Until then, unionization is growing in appeal for adjuncts at DePaul, who complain of low wages, job insecurity and an ambiguous role in shared governance within the university.

DePaul adjuncts are paid an average of $3,000 to $6,000 depending on their department. The nationwide average is just under $3,000 for a three-credit course.

A DePaul staff member and adjunct professor who spoke on condition of anonymity said, “one of the things that unionization and collective bargaining would likely be able to secure would not be one-off bonuses, but compensation that increases year-to-year or in some kind of progressive nature.”

According to emails sent from Holtschneider and denBoer last week, union dues, or the money members pay to union administrations, would amount “to hundreds of dollars per year.”

Greenberger said the dues paid to different unions vary, but “if you’re talking about adjunct faculty, it obviously couldn’t be that great. They’re not paid that much to begin with, which is of course why they want the union in the first place.”

The staff member, who has worked at DePaul for five years, said they had not been contacted by a union representative, but they support the union effort.

“That’s what Catholic social teaching affirms, is how collective bargaining and collective action can act as a counter-balance to stronger institutional forces or economic forces,” the staff member said. “I think it’s the right decision in order to find a better, equitable pay and a living wage for adjuncts.”

Holtschneider defended his preference against unionization and said adjunct benefits at DePaul are greater than at other institutions; adjuncts take home half their salary if a class is canceled, have access to medical and retirement benefits and are paid more than the nationwide average.

He said the “long-standing tenures” between faculty and adjuncts are likely to change with the involvement of a union.

“This isn’t going to change my life much, but it’s going to change the life for lots of these departments that are going to get formalized between the full-time and the part-time faculty,” Holtschneider said. “And I’d rather not have that. DePaul’s a family place, even though it’s big, it doesn’t feel that way … Now if we were treating them poorly, I would get it even more, but I think we’re kind of mostly above what most people are doing.”

Greenberger said it is likely unionized faculty will ask for better pay, defined working hours, health insurance coverage and access to office space and resources. A document on the adjunct portal lists among other things benefits that include medical, vision and dental insurance plans, a 403(b) retirement plan and shared access to office space and equipment.

But taking part in these insurance benefits is difficult, the staff member said.

“Your take home pay is so low that in order to (participate in insurance plans), you still have to make contribution toward health care,” they said. “The pay is just so low. Most people just have to hold onto that. It’s a luxury to put a portion of that paycheck towards medical care. So to suggest that it’s offered is a little disingenuous.”

According to Faculty Council Vice President Bamshad Mobasher, adjunct faculty issues specific to DePaul also include a lack of voice, as well as protections and privileges that full-time employees receive.

For instance, adjuncts are not allowed to sit on the Faculty Council, the body that represents faculty in DePaul’s shared-governance structure. And, Mobasher said, they are not covered by the university’s faculty handbook, which leaves them without rights that other university employees enjoy.

“There’s a grievance process for the faculty and we believe that also applies to adjuncts, but the administration basically says that it doesn’t,” Mobasher said. “So as a result of that, adjunct faculty sort of become the only group of faculty on campus — in fact the only set of employees on campus — that really have no grievance rights of any sort.”

Holtschneider pointed out that adjuncts sit on the contingent faculty committee, but overall agreed that Faculty Council “hasn’t been the place,” for adjunct representation.

“The shared governance at DePaul is really mixed practice,” Holtschneider said. “(In) some departments the part-time faculty sit in all the faculty meetings and they’re invited to all the faculty meetings if they want to come and they get a voice.”

But there are also other departments that don’t invite adjuncts and only full-time faculty meet, Holtschneider added.

“At DePaul it’s been a great variety of practice just as different departments have developed over the years. So there is no one practice I can give you because it’s been a broad variety,” Holtschneider said.

In one of the slides on the adjunct portal page, the university warned that in the case of unionizing, “it would be required by law to deal only with SEIU and its few, hand-picked faculty representatives, undermining DePaul’s system of shared governance and your participation in it.”

“The problem is that the adjuncts are really not a part of the shared-governance process,” Mobasher said. “So in that sense, they really do not have any power.”

“And the university’s argument right now is ‘okay, we’d rather maintain the direct relationship with adjuncts.’ But what that means is direct relationship or direct discussion between the supervisor and one adjunct,” Mobasher said. “The whole point of the union is to change that picture so that there’s more power in numbers, so you have a group of people negotiating rather than just one person talking about their own specific case.”

The issue of faculty unionization principally comes down to a 2014 NLRB ruling against Pacific Lutheran University, which found that adjunct faculty at private universities have the right to unionize given their limited rights to participate in university government and other ruling bodies. This is in contrast to tenured and tenure-track faculty who are designated as “managerial employees” and participate in significant decision-making processes and are not covered by the Labor Relations Act.

While part of the final decision by the NLRB in the Pacific Lutheran case was that faculty members not engaged in religious instruction could organize, Greenberger said it is highly likely that this decision would be contested by the university by an appeal and the issue would be sent to the courts to decide.

As it stands, there is no decision on the issue of a religious institution appealing against unionizing faculty on the basis of religious freedom rights. In the Pacific Lutheran University case, the employee who filed the case to the NLRB withdrew the petition for the union and the university did not file for any kind of appeal.

“However there are other union organizing drives underway at different religious education institutions, so the issue is likely to present itself again, and ultimately the board’s decision, in one of those decisions will be appealed to the courts and the courts have the last word on this, not the board,” Greenberger said.

What the courts will consider in the case of an appeal, Greenberger said, is how closely faculty trying to unionize are to functions tied directly to the religious institution’s mission.

“There’s no question that religious institutions can discriminate in favor of people of the faith holding positions that involve clerical functions,” Greenberger said. “In terms of Catholic practices, if someone is teaching doctrine, you can insist that they be Catholic … the further you move away from the religious focus of the institution, the greater the likelihood the courts will prohibit discrimination.”

As for forming a union, Greenberger said the process is fairly straightforward, and typically an election can be scheduled quickly. But this is not the case with resistant employers.

To begin the process, workers must campaign for support from 30 percent of their cohorts, who pledge their commitment by signing union cards.

Once 30 percent of the workers sign union authorization cards, the NLRB will call for and conduct an election among the workforce for or against the union. The election uses a secret ballot, and if the vote passes, the NLRB certifies the union and begins supervising the contract negotiation process between the employees and the employer.

An email sent from denBoer Jan. 19 said that a faculty member mistakenly signed a union card, after being “led to believe the ‘green card’ was a request to receive more information about the union.”

“Faculty get handed a card to sign, and (union representatives) say, ‘if you sign this card you’re asking for more information,’ and it’s not,” Holtschneider said. “That card means giving them the exclusive right to represent you as a union. At other universities it’s a frequent unionizing practice. And we’ve seen it at others. For the first time last week we had faculty coming to us saying ‘I didn’t realize what I just signed, I was just told, how can I undo this?’”

For DePaul adjuncts considering signing a membership card, the university created a webpage of information on unions called “Adjunct Info Hub.” Although the university states in its official policy on unions that it “is not anti-union,” many of the links painted a bleak picture of unions, specifically the SEIU.

One slide asks “with whom would you rather work?” and presents only two options: DePaul, with several benefits listed, or the SEIU, with several negative attributes. Another slide questions the paying of union dues, and the last slide is titled “Don’t let the union silence your voice.”

“It’s clear, based on reading a lot of the information that’s been made available on the adjunct information hub, the institution’s stance is definitely one where they are trying to position or frame the unionization efforts as being detrimental for the university and for the relationship with faculty,” the staff member said. “It’s difficult. On one hand they’re saying you’re free to choose, but on the other hand they’re trying to persuade adjunct faculty to not sign union authorization cards.”

Holtschneider said the tone of the web portal did express the university’s preference not to unionize.

“We get to tell you what our thoughts are, right? And our thoughts are, we’d rather just operate personally rather than through an outside third party talking between us,” Holtschneider said. “We get to speak too. Everyone gets academic freedom at the university to speak their mind and that’s our preference.”