At rallies, politicians use music to make a poignant statement about the way they see themselves and their ideals. On Super Tuesday, Bernie Sanders left the stage of his early victory speech in Vermont to the sounds of David Bowie’s “Starman.”

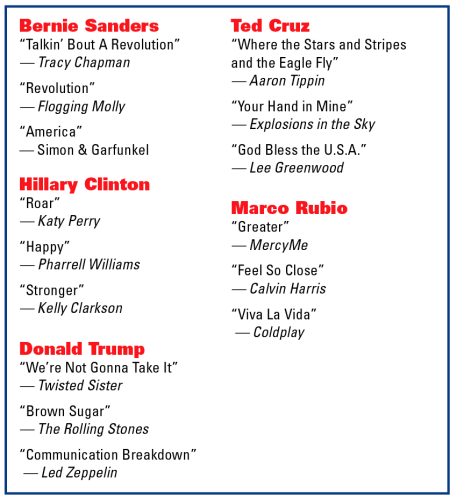

Twisted Sister’s “We’re Not Gonna Take It” has become a Donald Trump rally anthem, while Hillary Clinton’s campaign spent thousands of dollars in 2015 on music research to compile a list of campaign-friendly songs, according to a Rolling Stone article last month.

Music is important in politics — choosing the right kind of music is even more important.

“Music selection has to match the intent of the communicator and the music has to fit the occasion,” DePaul marketing professor D. Joel Whalen said. “It has to move the audience.”

“When one hears music, it takes us to a deeply emotional place,” Whalen said. When one hears music with a group of people who share the same ideas, it becomes a magical experience.”

The music goes beyond rallies and into advertisements, as well. A Ted Cruz advertisement used the Explosions in the Sky song, “Your Hand In Mine.” Before the Iowa caucuses, Bernie Sanders released a commercial using the Simon and Garfunkel song “America.”

“We’ve borrowed quite a bit from the commercial world of marketing where we see the use of music to create a certain feeling or emotion around a product,” marketing professor Bruce Newman said.

Newman is the author of the book “The Marketing Revolution in Politics,” which details the marketing strategies politicians have at their disposal.

Newman explained that music gives politicians the ability to create and cement an emotional connection and reaction from the public. They just hope it will e stablish a connection with voters.

stablish a connection with voters.

But are politicians allowed to use any song they wish for their campaign? Not necessarily, as there are legal obstacles and potential backlash from the artists themselves.

“The use of music in political campaigns is a bit more complex than many realize,” DePaul School of Music professor Alan Salzenstein said. “The common misunderstanding is that the use of a song in a political environment is strictly a copyright issue. The copyright concern is typically centered around the relatively simple scenario when a politician uses a song, or portion, during a live rally.”

“For use of songs at the usual live venues for campaigns, public performance licenses are needed. If these licenses are acquired, either through the venue or by the campaign itself, then they would be in compliance with the copyright law,” Salzenstein said.

The use of music in a political ad or at a rally does not always equal an endorsement for the politician by an artist. Ted Cruz was forced to pull the ad using Explosions in the Sky after the band said they were not fond of the Texas senator. A similar incident played out in 2012 when Paul Ryan and Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine traded jabs, with Morello saying the band despised Ryan and everything he stood for. And although a Sanders’ campaign spokesperson told CNN in January that “America” was licensed legally, they clarified that it was not an endorsement of any kind from Simon and Garfunkel.

Last month, Adele said that Donald Trump did not have her consent to use her song “Skyfall” at rallies. Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler had a cease-and-desist letter issued to Trump’s campaign team to stop using “Dream On.”

Rifts between artists and politicians over the use of music are nothing new. In 1984, Bruce Springsteen attempted to distance himself from being referenced in a speech by Ronald Reagan during his re-election campaign. The campaign also used his song “Born In The U.S.A.,” which Springsteen said was misunderstood by them.

More recently in 2008, Obama’s campaign team used Sam and Dave’s 1966 song “Hold On, I’m Coming.” Singer Sam Moore asked the campaign to stop using the song, saying that he was not endorsing the campaign, and his voting preference was a private and individual matter.

Salzenstein said that things get more complicated when an artist does not want to be associated with a political campaign. Artists can, in some instances, use legal action, even if a campaign is adhering to proper copyright laws.

“A campaign, while complying with copyright, may be in violation of other laws, such as right of publicity and the Lanham Act, which provides for situations of false endorsement,” Salzenstein said. “These laws protect image and identity, which would therefore require permission from the artist.”

“So, when an artist is unhappy with his or her work being associated with a political campaign, it can go beyond the licensing required by copyright law,” Salzenstein said. “The waters get murkier with a different set of legalities when you bring into the conversation issues of image and false endorsement, which can be extremely impactful to a musician’s career.”

Despite any potential legal troubles, music seems to have cemented its usefulness to politicians hoping to connect with audiences. For that reason, Donald Trump will continue to use the Rolling Stones’ “Brown Sugar” before rallies, and Hillary Clinton will be using Jennifer Lopez’s “Let’s Get Loud” and Kelly Clarkson’s “Stronger” from her curated playlist, likely for the duration of the campaign.