A funny story became the chance of a lifetime, and in the end, DePaul sophomore James Novack walked away. It wasn’t an easy decision, but he knew it was right.

He isn’t alone. Novack, a talented musician, is like many college students who leave their performing days behind them in high school — something to save for the yearbook. Under pressure to choose a career path, would-be artists choose majors to find “real jobs” that will offer better job prospects and salaries.

But as Novack settled into his new life at DePaul, he was given another shot.

It was a “you wouldn’t believe…” kind of story. Novack met the manager of Bronzeville gospel rapper Sir the Baptist in a Chicago Bagel Authority, and agreed to interview the fledgling artist on his show at Radio DePaul. That was during the winter term.

Sir the Baptist, or 27-year-old William James Stokes, was signed to Atlantic Records the following spring, hit it big and Novack called for another interview. On May 10, Stokes came on the show. He was playing at Columbia College Chicago’s ManiFest festival that weekend and then touring to New York to play on Late Night with Seth Meyers the following week.

He wanted Novack to come with him.

“He came on the show and said, ‘I need you to sing backup,’” Novack said. “He told me on air. I almost fainted. My co-host was sitting there in awe. I’m still in shock because this all happened in one week.”

During the interview in December, Novack and Stokes were talking music, and Novack ended up showing off one of his demos. “He loved it,” Novack said.

The offer came as a shock to Novack and his family, but in the end, no one was surprised.

“(They said), ‘We were waiting for this to happen to you,’” Novack said. “Everyone still thinks I want music. It was such a big part of my life until two years ago. My mom was telling everybody and their mother and I had to keep things under wraps for awhile until I could announce it.”

It was after playing the show at ManiFest that weekend that Novack realized he had to turn down the offer to tour.

“Not many people get to experience something like this, and people’s lives change overnight,” Novack said. He would have to miss finals to perform in New York, putting him behind in his major in neuroscience. He already has to do a fifth year to go to medical school. “I was weighing options and came to the realization — I think I’m on the right track already.”

His mom asked if he was sure. He said, “when you think of things like this, you have to separate your head from your heart. My head said do it. My heart said, ‘your talents are called elsewhere.’”

Getting another taste of performing made the decision difficult.

“I got on stage and I’m like, ‘this is really exciting and exhilarating’ and I loved it,” Novack said. “I think the one experience was enough for me. But at the same time, I want more. I’m still torn.”

Coming into college, Novack made the decision not to pursue music. He was accepted into the music school, but felt such a strong vibe of competition and judgment that he decided wasn’t for him.

His story reads something like Paolo Mazza’s, a transfer student who vacated his spot in the Theatre School for a career in communications and marketing. Both were accepted into competitive conservatories, both had cautious but firm support from their parents, but both said no.

“Compared to some of my other friends who were dead set on it —I knew I was good — but I wasn’t competitive enough,” Mazza said. He knew there was uncertainty in getting a career in theater and it would be tough just to afford four years at DePaul’s Theatre School. So he went to community college instead until he could transfer.

“I knew my parents wanted me to get a job that was stable and not as uncertain as a job in theater,” Mazza said. “They didn’t necessarily say it, that they were unsupportive, but I knew they were looking for something more professional, in the sense financial-wise.”

When he told them his decision to move on from theater, they were relieved.

For Mazza, his parents, and even Novack, hesitation to enter the entertainment industry is understandable.

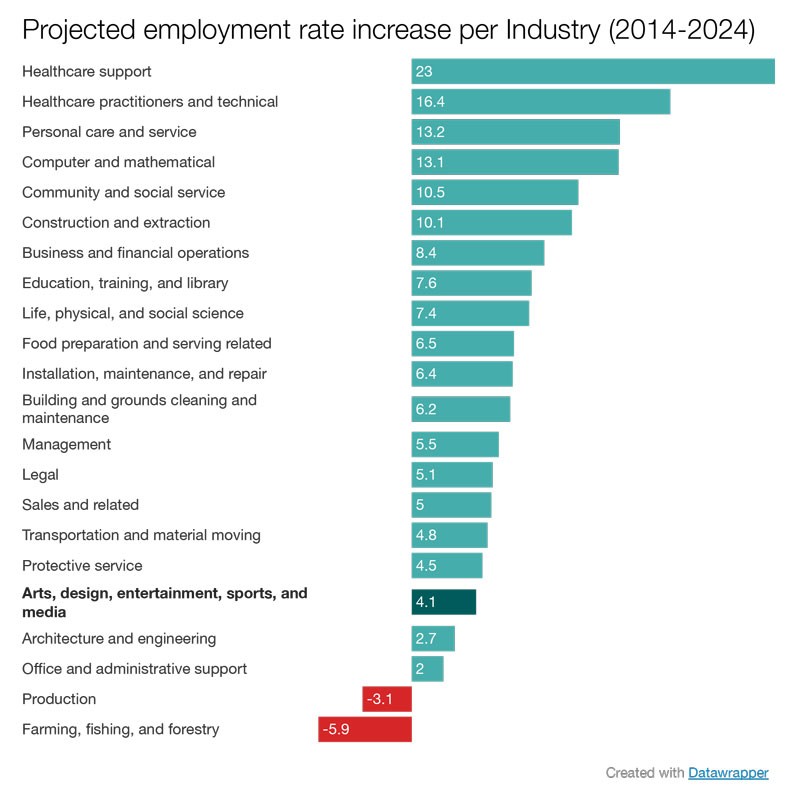

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were just over 460,000 jobs as actors, music directors, composers, producers, directors, musicians, singers, dancers and choreographers in 2014. Expected job growth for the arts and entertainment industry, including sports and media, is only 4.1 percent over the next 10 years.

In 2014, one third of all actors worked part-time, and at least 20 percent of other arts professionals were self-employed. Pay rates were harder to define. Median actor rates were reported as $18.80 an hour, while a producer or director could reach a median salary of $68,000 a year.

Levels of education also vary. In all industries, generally speaking, having at least a bachelor’s degree correlates with higher salary. The median salary for those with just a high school diploma was $36,000. Then salaries jumped from $50,000 and $70,000 with an associate’s and bachelor’s degree respectively. But education and experience for careers in the arts ranged from having no credentialed education with no experience to having a bachelor’s degree and years of experience.

Facing all these odds, Dexter Bullard is an example of those who made it. With a comfortable office in the new Theatre School, Bullard is the head of graduate acting and artistic director of the Theatre School Showcase. His credentials are impressive, varied and he’s won awards for his work.

Looking back at his 18-year-old self, fresh out of a small town in Pennsylvania, auditioning for shows at Northwestern University was intimidating, to say the least.

“Coming into Northwestern, I was a much smaller fish,” Bullard said. “I was the lead in my high school (play), and all of a sudden I wasn’t well cast.”

Bullard wasn’t cast for much of anything, and doubts about his talent and looks dampened his confidence. By his sophomore year, he was running out of encouragement.

He kept pushing forward, and by his junior and senior years, he received the feedback that motivated him to improve his skills. By graduation he knew he wanted to direct, and through his connections landed gigs until finally directing a hit at Next Theatre in Chicago when he was 24.

From there he took risks, stayed in touch with influential friends and continued learning. There was a period where he waited tables and sold cell phones, but this was all part of his journey, he said. It takes time to build a reputation in the arts.

“I guess I had an actor’s bone in me. And then I continued to pursue it,” Bullard said. His parents were supportive, but not completely. “They said, ‘you won’t make a living. You need to fall back on things,’” Bullard said. “Now they know they didn’t need to be as nervous as they were.”

But as an academic and mentor to college kids, he understands the doubt.

“I encounter 32 18-year-olds (a year) who are starting their journey in conservatory training,” Bullard said. “They have all the stories possible. (Some have) been doing it since the day they were born — age four, already been in commercials, lots of experience. Or their parents are in the theater or movies, or whatever. Or you have some that, literally in their sophomore year of high school, fell in love with being in a play and turned a corner.”

“But all of them have that argument to make when they go back for Thanksgiving, and I help them with that,” Bullard said. “Everyone says, ‘you’ll be a waiter,’ or ‘you won’t be making money.’ You think you want to be someone else.”

Part of convincing the family is convincing yourself, Bullard said. Even those like Mazza, who don’t pursue the arts right away, aren’t disowned from the industry.

“I definitely think where you go and what you study and what your degree is in is an example of your experience, but not who you are,” Bullard said.

For all students, choosing a career path in high school brings mixed results. In 2015, 332 freshmen enrolled as undeclared majors at DePaul, almost double the number of freshmen enrolled in any other major. This doesn’t account for students who change majors during the rest of college.

For many, choosing a major is like turning a page. For Novack, his future lies in neuroscience. Or, so he says.

“I have these amazing opportunities that come my way and I have to choose what I want to do,” Novack said. “Right now it’s hard because I know these opportunities are going to keep coming.”

For now, he’s sticking to the plan.