When Julian Gomez walked across the stage at Allstate Arena this June, diploma in hand, tassle now on the left side of his cap, he couldn’t have predicted that two weeks into his new job there would be talk of a strike.

Fresh out of his graduation robes, Gomez went back to his old elementary school, William H. Seward Communication Arts Academy Elementary School, to teach fifth grade. As one of 421 elementary schools in the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) district, Seward is facing budget cuts that may impact the resources and programs they are able to provide their student body. The school has faced cuts to its resources before, Gomez said, and the result is palpable.

Gomez loves his job. He said it feels good returning and giving back to the community he comes from, but the problems with CPS can’t be ignored. Before returning to Seward was even a thought, his older sister warned him about the problems during her first year at CPS when he was a freshman at DePaul.

“I’m very aware of the losses — the arts, the after school programs and others,” Gomez said. “Because of budget cuts there aren’t enough resources, and even with the resources we have it’s not enough to work with students at their levels.”

Members of the Chicago Teacher’s Union (CTU), the union representing teachers, paraprofessionals and clinicians of CPS, authorized a strike last week that could start Oct. 11. It will be the first CTU strike since 2012. Negotiations on contracts for the district will continue until the Oct. 11 stirke but the financial straits of CPS jeopardize students, teachers and resources going forward.

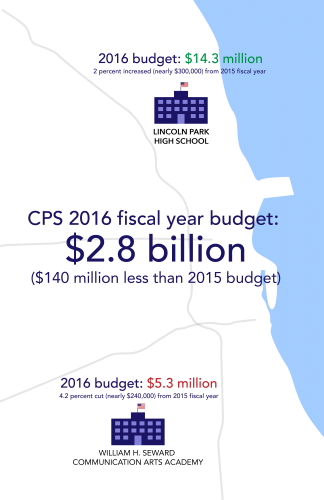

CPS is comprised of 480 elementary schools and 172 high schools. Of those schools, 125 are charters. The money to keep the schools up and running is slowly dwindling. This year the budget is $2.8 billion, which is $140 million less than the 2015 fiscal year. The effect of the budget cuts depends on the area.

Lincoln Park High School, an affluent school in an affluent area with an International Baccalaureate program, will see its budget rise by 2 percent, or by nearly $300,000, to $14.3 million.

Seward Elementary, which faces continued cuts to resources and programs in the Back of the Yards neighborhood, will see its budget cut by 4.2 percent, or by nearly $240,000, to $5.3 million.

When cuts happen it is largely the arts — music and painting for example — that are cut first. The impact of those losses trickle down from there, slashing the number of books available to schools or after school programs to help students. To keep all schools up and running, programs like art are often terminated at schools in underprivileged neighborhoods while more privileged neighborhoods — drawing on their income taxes — are able to continue to provide those programs.

Ronald Chennault, associate professor of social and cultural foundations in education and associate dean of educational policy and research at DePaul, said CPS’ problems could stem from the fact that it’s a “large and complex urban level school district. It’s not isolated from the larger context of the city and the world.”

“These problems aren’t new,” Chennault said. “This is a particularly challenging time for the city and the state in regards to money and culture. Providing a high quality education requires a lot of financial and human resources. Without those students suffer.”

At Seward, Gomez said the result of cuts to resources has already been seen. Gomez said that math levels dropped from when he attended the school, going from 60 percent of students meeting the math attainment level set by the state to 38 percent.

“(There has been a) drastic change in levels and the curriculum has changed,” Gomez said. “We plan to bring (resources) back to help the current situation, but that also depends on the budget.”

For long-term success, CPS teachers and CTU organizers have cited a need for classroom resources such as new textbooks and desks. Resources, of course, require money. Student-based funding comprises a large part of each school’s budget, as well as CPS’ budget as a whole. Some schools, like Seward, that are facing enrollment decreases are also being knocked monetarily. A property tax hike announced by the Chicago Board of Education in August will raise around $250 million, but the money can’t be used until the 2017 fiscal year.

There are programs that try to offset the loss of resources, especially where teachers are concerned.

The Golden Apple Foundation aims to develop future teachers who then promise to teach in a “school in need” for five years. Many CPS schools, as well as schools in the suburbs and rural Illinois, would fall under that umbrella.

For Bella Fioretto, a Golden Apple scholar watching the strike situation unfold, questions about teaching in CPS and whether or not they would get the support of officials in charge of CPS, have been raised. The work she has done with students already, however, make Fioretto want to continue in CPS.

“The only reason I keep thinking about teaching in CPS is because of the students,” Fioretto said. “Most of my time at DePaul, I have been working with CPS students. CPS students need great teachers. They need teachers that will provide opportunities for them to succeed regardless of their background. Education is for the kids, it should always be for the kids.”

For Gomez, contract or not, the kids are the reason he returned, and their success is what keeps him going. He wants his story to be one of inspiration for his students.

“I want students to look at me and say ‘I could do the same thing,’” Gomez said. “They can succeed in school and in the Back of the Yards neighborhood. The teachers and staff will help them, but it’s up to them, too.”