OPINION: What free-speech advocates need to know about Assange

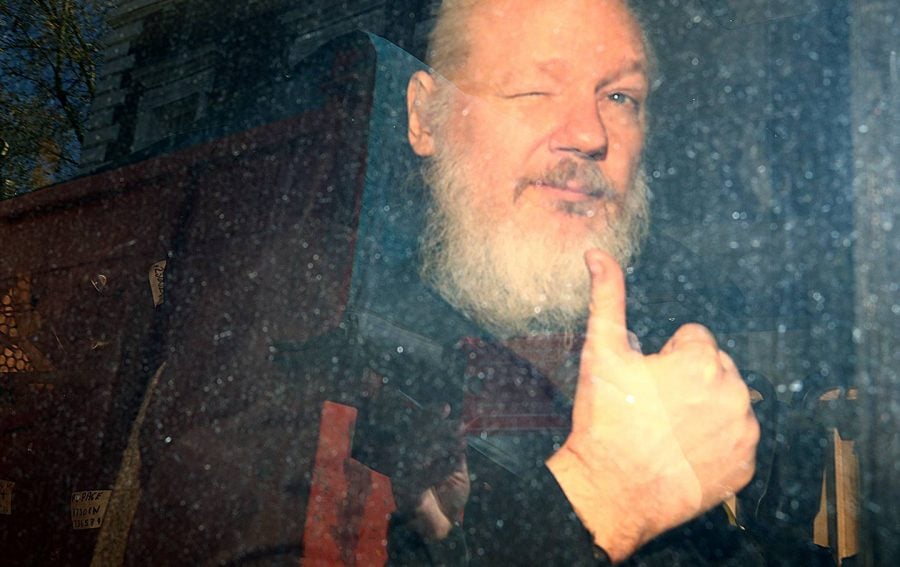

Wikileaks founder Julian Assange after being arrested by British police and removed from the Ecuadorian embassy.

The high-profile international news coverage of federal charges aimed at WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has brought attention to issues of press freedom in an age of digital information security concerns and increased use of government power to pursue whistleblowers and journalists.

Digital tools make infiltration of secured databases difficult to track and possible from anywhere around the world. Therefore, the Assange case raises new important questions about the constitutional rights of sources who share digital files of classified information in the public interest and the legal responsibilities of outlets, traditional or not, to whom they leak files.

Assange drew international attention in 2010 when WikiLeaks started posting classified documents leaked by Chelsea Manning, an Army intelligence analyst who had downloaded files from a classified computer network. Then in 2016, WikiLeaks published stolen emails by Democratic Party operatives that the Russian government hacked as part of an operation to damage Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign and benefit Donald Trump.

The questions of which laws the government says Assange broke, how he will be prosecuted for his alleged crimes, and under what statutes he may yet be charged are key considerations for free speech advocates.

For starters, WikiLeaks seeks out and publishes information that powerful people would rather keep secret, including classified national security materials, and attempts to protect its sources. That’s generally the same approach that investigative reporters at traditional news organizations follow and those practices are immunized by the First Amendment.

The indictment unsealed on April 11 charges Assange with actions beyond what a journalist is legally permitted. The government says Assange conspired to commit unlawful computer intrusion working in cooperation with Manning to break code to permit her to log into a classified military network under a false identity.

Conventional journalists aren’t protected by the First Amendment if they break the law in the process of reporting the news, but they can receive and publish information like what WikiLeaks posted if it serves the public’s interest. This constitutional protection comes from the 2001 Supreme Court case of Bartnicki v. Vopper, which established that journalists can publish news about political issues even if that information was obtained illegally by the source so long as the journalist did not participate in the illegal acquisition. It remains to be seen if that same standard would be applied to classified information, particularly material deemed crucial to national security.

Right now, prosecutors are not pursuing Assange on speech-related charges. However, in the Obama and Trump administrations, the government has been quite active in charging officials with leaking information to reporters under the century-old Espionage Act. Of the 13 Espionage Act prosecutions in U.S. history, nine have come in the past decade.

A journalist has never been prosecuted under the Espionage Act, but Manning’s 2013 court-martial conviction included espionage-related charges as Assange’s source. Assange is expected to fight extradition to the United States by arguing that his prosecution is politically motivated, meaning a trial is not imminent.

Ultimately, the First Amendment protects the rights of people who commit legal acts of journalism, regardless of their political views and whether they are non-citizens or loathsome characters. Assange has spent almost seven years living in the Ecuadorian embassy in London avoiding extradition not only to the U.S. but also Sweden, where he faces charges of sexual assault.

Developments in his case, however slow, will be closely watched by journalism organizations and civil rights groups because of what Assange represents about all of our First Amendment freedoms.

Jason Martin, Ph.D., is associate professor and the chair of the Journalism Program in the College of Communication. His research and teaching focuses on press freedom and First Amendment protection for journalists.

Peonshch Yeffen • Aug 14, 2019 at 1:15 pm

It seems like the difference between low IQ and high IQ is why information is hidden from the gradient for reasons of intelligence and knowledge and value… two examples: 1+1+1=3, this is proof of infinity! So what is to hide is based upon the gradient within low to high IQ’s among humankind.

An assessment of the Julian Assange case is based upon Edwaerd Snowden’s cache of documentation, which none has been released, also, the case of Snowden was written by algorithms before he was born because of non-sentient “ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE”! An interesting aspect for Super-Intelligent-Cognitive-Machines is the genderless property of the value(s)…

Reference:

Go to information Philosopher, Molecular Visualizations !

Go to Alien Interview | Real or Fake?? | YOU DECIDE | Project Blue book UFO ~9:52

(SQiU can forward sight into immediate light years while navigating a crystalline structure beyond the one speed of light!)