‘Know what you owe’: Student loan advice from a professional fitness adviser

MCT for The DePaulia

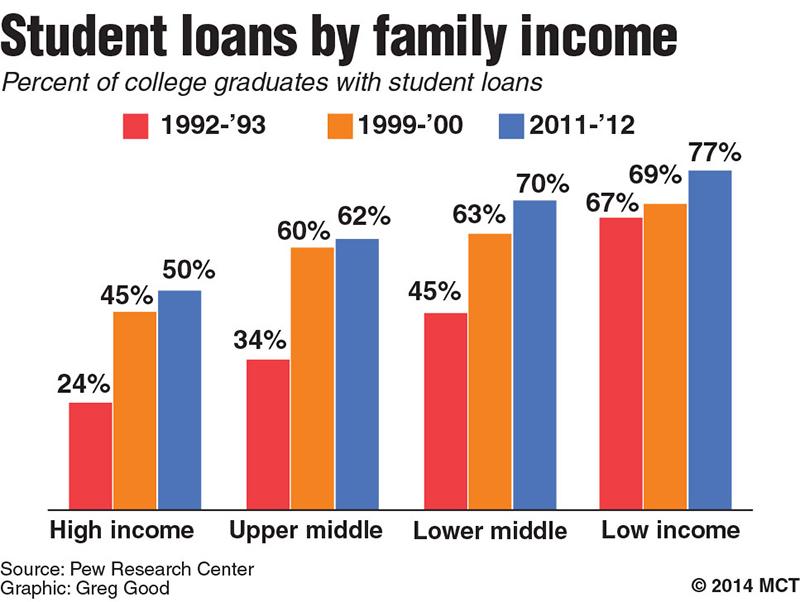

National student debt burden in the United States has undoubtedly grown in the last two decades. (Greg Godd | MCT Campus)

Natalie Daniels, a short woman with magenta glasses and a bright smile, sits in her office tucked away in the back of DePaul Central, separated from the bustle of the Schmidt Academic Center.

Two computers are propped up on her desk as she quickly types out numbers into a loan interest calculator with skill. She flits between tabs, viewing students’ financial aid packages and laying out personalized loan options for her next appointment.

“The box of tissues on my desk is not there because I have a cold,” Daniels said. “People cry in my office a lot. It’s stressful and all I can do is be really honest about the numbers to make sure students can make the most informed decisions.”

Daniels started working as a financial fitness advisor at DePaul in 2007, climbing the ranks to assistant director in 2015. Her priority is to help students, faculty and alumni practice financial wellness, which she describes as “having an idea about your finances, having a plan and having knowledge of where your money is going.”

About 60 percent of her appointments revolve around student loans, with one half of the students seeking further information on terminology and big picture, and the other half seeking help with repayment plans. Last year, Daniels had 365 individual appointments plus several workshops she puts on each year.

“My biggest advice to any person when it comes to finances is know what you owe,” Daniels said. “It’s crucial to have a good understanding of how much you’re borrowing, what it is going toward and what that repayment will look like in one, five and 10 years.”

At DePaul, where the average student debt after graduation is $29,000, money weighs heavily on students’ minds.

“I wish it wasn’t a concern because it makes me nervous sometimes that something will happen that will prevent me from continuing my education,” said Belinda Andrade, a sophomore majoring in public relations and advertising. “I don’t know what I would do.”

Andrade, who lives in Humboldt Park, said she has been worrying about money since high school. Her mom works extra jobs on top of teaching to pay for tuition with the help of scholarships, while Andrade takes care of bills, food and school supplies herself.

She says she began accruing credit as soon as possible so she could qualify for loans in the future, and she constantly saves money to keep a quarter’s worth of tuition in her account at all times, just in case.

“It can be really stressful to have that kind of worry on me at all times, but it’s better to be that way than just kind of hope everything is going to work out, at least for me,” Andrade said.

A server at a ramen restaurant and student-worker at the Women’s Center, Andrade struggles to find ample time to spend on her school work and social life.

“I recognize that I need to have a social life and I get to go out when I want, but sometimes that constrains my schoolwork,” Andrade said. “I try to get everything I need to get done and do it well, but there is no balance for me. It’s more so planning how I want to choose to spend my time on one thing to sacrifice another thing.”

Andrade isn’t alone.

Chiratidzo Sanyika, a finance major and sophomore international student from South Africa, said she finds that her financial situation affects her relationships with both her friends and family. Sanyika’s father pays for what’s left of her tuition after her scholarship and living expenses.

Because her family covers the costs of attending DePaul, Sanyika often finds herself under intense pressure to perform well academically. Just like Andrade, she also battles balancing her work, studies and social life.

“My financial situation affects some of my friendships,” Sanyika said. “Some of my friends don’t feel the need to pay me back for things because they think that I can get money from my parents whenever I want. It puts me in an awkward situation because even though I should get the money that I’m owed, I know that some of them are really struggling financially.”

Students are often surprised by the costs of socializing.

Freshman public policy major Chloe Troub of Chicago suburb Crystal Lake believes high schools and colleges should do more to educate young adults on the overall costs of living.

“I don’t think high school really prepares you for how expensive college could be,” Troub said. “Outside of the cost of tuition, there are a lot of things that students are not told about, like books and rent and eating out.”

Extra expenses like social outings and entertainment, as well as unrealistic housing expectations, can push students closer to the danger zone and outside of their budget, which worries Daniels.

“Having this mindset where your expected lifestyle and living expectations lead you to start spending and borrowing to reach those expectations is one of the biggest financial mistakes students make,” Daniels said. “You’re not going to have your dream apartment. It’s ok.”

Daniels believes that as students get more comfortable talking about finances, education will continue to grow while their fear and stress shrinks. One day, she hopes that high schools and universities will mandate financial wellness training so that everyone can have the tools to succeed.

“Knowing the basics of personal financial health is my dream for all students,” Daniels said. “It’s a good dream. It’s a hard dream to realize, but it’s a good one to have.”