DePaul students provide hope, mentorship to Chicago’s growing refugee communities

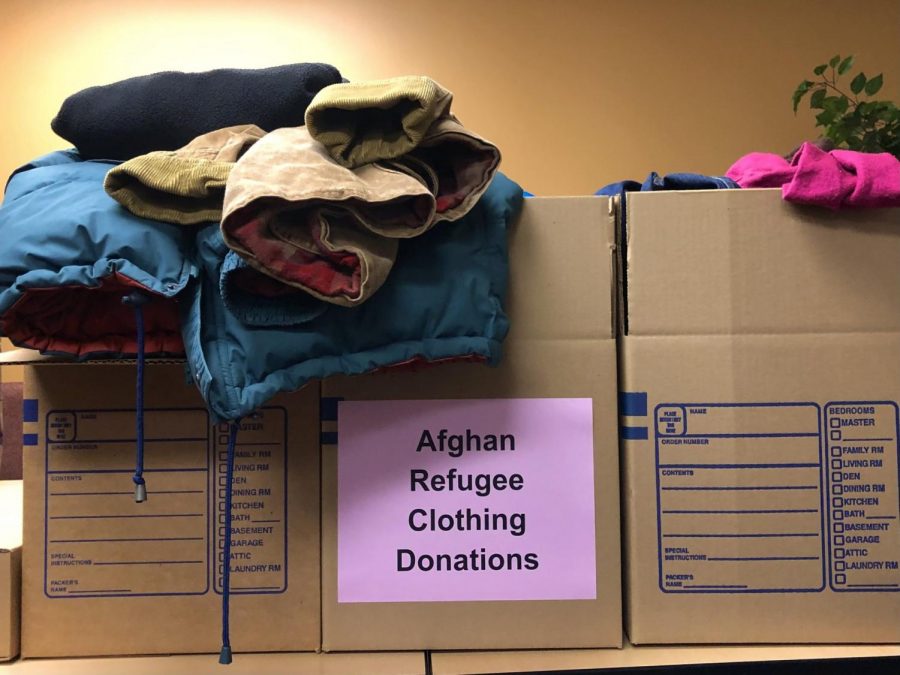

Chicago’s influx of Afghan refugees has overwhelmed aspects of the city’s resettlement infrastructure, leaving gaps in support services. DePaul students are working to bridge those gaps by supporting these new members of Chicago’s communities through case management and mentorship.

The Afghan Placement and Assistance program, which created an expedited resettlement process for Afghan refugees in the wake of the Taliban regaining control of Afghanistan, has overwhelmed many resettlement agencies with U.S. cases. Areas with strong refugee resettlement services and those with preexisting Afghani populations like Chicago are prioritized for settlement.

Emily Parker, a second-year masters student in the refugee and forced migration studies program, is a refugee resettlement caseworker with Catholic Charities of Chicago. Parker works to provide refugees housing and address other immediate needs within the first months of arriving in the U.S.

“No one anticipated the Afghanistan situation, it all happened incredibly abruptly,” Parker said. “So, we have kind of just had to roll with the punches and completely transform our resettlement team.”

“It’s most intensive when [refugees] first come, within the first 90 days,” Parker said. “I pretty much hit every base with regard to housing, cultural orientation, public transportation orientation, everything that someone would need to acclimate to life in Chicago.”

The initial 90-day period is graced with state and federal funds for refugees including Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits for healthy foods, job placement and funds from the Illinois Department of Human Services. Resettlement agencies provide further case management assistance for up to five years.

Without much advance planning to secure housing, furniture and job opportunities for arrivals, many Afghan evacuees are greeted with temporary solutions.

“Because we have such short notice, housing is the hardest thing,” Parker said. “Our community resource developer has a really hard time because we’re leaving our clients in hotels and extended stays for weeks until we can find them an apartment. It’s really hard to find landlords that will accept the terms that aren’t horrible living conditions and not making our clients subject to dirty buildings,” Parker said.

Chicago’s other refugee communities are struggling during Covid-19and shifting city policies. The Rohingya community in Chicago is one of the country’s largest with over 1,500 people according to the Rohingya Culture Center. As an ethnic and religious minority in their homeland of Myanmar, Rohingya people are subject to persecution and unable to access education and other services in Myanmar.

DePaul graduate student Sarah Pajeau works as a program manager at the Rohingya Culture Center in West Ridge. She coordinates community events and provides job, educational and community support after the bulk of the resettlement process.

“We’re at a point of limbo,” Pajeau said. “There are people who’ve been here for almost a year now … and they haven’t been able to find work, and [resettlement programs] only help for three months.”

The pandemic complicated resettlement efforts. During Chicago’s first shutdown, refugee’s jobs secured as part of resettlement were lost in the blink of an eye. Resettlement organizations provided virtual services, but those without the appropriate technology or English fluency found them hard to access.

“Three months even outside of the pandemic isn’t enough,” Pajeau said. “But especially during the pandemic, there’s just no way to figure it all out in three months.

The Rohingya Culture Center has remained open throughout the pandemic, providing walk-in support for those in the community — whether it be applying for unemployment or stimulus benefits. Leaders have organized Covid-19 vaccination and flu shot clinics, voter registration drives and tutoring for children. The Center works hand-in-hand with other resettlement agencies in the city.

Aside from domestic concerns, many refugees are concerned for their families abroad.

“So many people have family back home and are waiting for family to be resettled,” Pajeau said. “Everybody here has somebody abroad, so we’re just hopeful that more people will come.”

RefugeeOne, the largest refugee resettlement agency in Illinois, has worked to resettle over 18,000 arrivals since 1982 with the help of DePaul’s student volunteer coordinators.

Elvina Ibricic, a senior in the Driehaus College of Business, has been volunteering with refugee kids since her freshman year. She now co-coordinates a team of students to tutor and mentor refugee children at RefugeeOne.

“It might be helping a kid learn their ABCs, or it might be teaching them trig,” Ibricic said. “We just like hanging out with them — kind of like a friend in a way.”

Covid-19 restrictions posed problems for the program, as many kids opted out or struggled to focus on virtual tutoring and mentorship. Ibricic shifted to creating videos for her mentees on everything from geography to filming herself cooking simple recipes for the kids to replicate at home. Today, the program has resumed visiting RefugeeOne in person at a limited volunteer capacity.

For her, giving back is at the heart of her work with the Office of Mission and Ministry. Ibricic’s family is from Bosnia and Herzegovina and settled in Iowa before she came to DePaul.

“It was very personal for me because my family came to the states as refugees,” she said. “So I wanted to be able to help families and kids who are kind of like me and my family.”

All DePaul students have a unique opportunity to assist refugees making their home in Chicago, whether it be in resettlement, ongoing support or mentorship.

“A lot of our Afghan arrivals are college students that had their education interrupted, and they’re trying to get back [to it]. Referring them out to DePaul students who have been through the college application and admissions process [would] help out with that,” Parker said.

United Nations Refugee Agency data indicates that three percent of refugees access higher education. DePaul students can help reach the U.N.’s goal of 15 percent refugee student attainment of higher education through mentorship and advocacy.

“I would tell students to advocate for … refugee students so they can have access to DePaul, in a similar way that those of us who were born here and had parents who could teach us about what the ACT was and what applications were and how to apply for college,” Parker said.

Chicago’s web of social service providers and Illinois state funding has fostered a diverse and culturally rich haven for many fleeing oppression. From Devon Avenue’s robust array of small businesses, religious organizations and restaurants to the affordable housing flanking it, West Ridge has long been the center of Chicago’s immigrant and refugee communities.

“Chicago is a good city because it has a long history of welcoming people from various communities. It’s a sanctuary city,” said Rajit Mazumder, DePaul University associate professor of refugee and forced migration studies.

Catholic Charities of Chicago, the DePaul Office of Mission and Ministry, RefugeeOne and the Rohingya Culture Center are seeking volunteers to assist Chicago’s vibrant refugee community.