Author of one of the most banned books in America details their activism

Will Long for The DePaulia

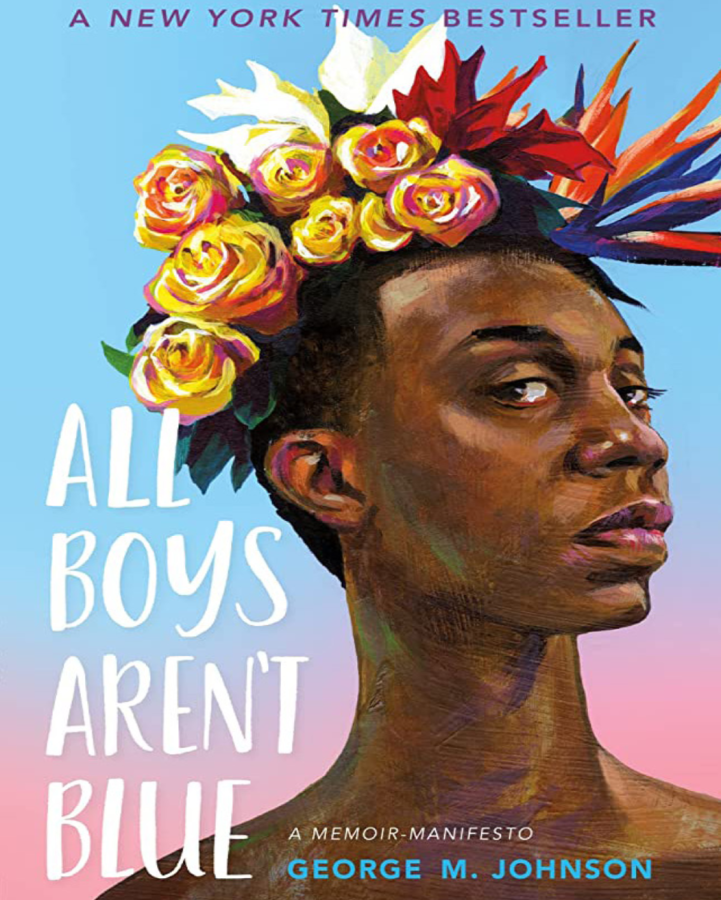

New York Times Bestselling Author George M. Johnson speaks about their latest book “All Boys Aren’t Blue” at the Lincoln Park Campus on Thursday March 3.

Excited whispers filled the room as community members and DePaul students awaited best-selling author George M. Johnson to grace the stage.

Johnson, a Black queer nonbinary author, activist and journalist, wrote their memoir “All Boys Aren’t Blue” in 2020 and it soon became a New York Times bestseller, as well as the third most-banned book in 2021.

Despite the push for banning Johnson’s memoir, they exuded confidence while reading their chapter “You Can’t Swim Wearing Cowboy Boots,” from their memoir. They recounted that while their cousins wanted new sneakers, Johnson wanted cowboy boots and getting over their life-long fear of water.

Afterwards, a panel featuring DePaul faculty and students started a conversation with Johnson about their work, life and activism regarding book banning.

While recounting their family dynamics, Johnson kept in mind how they portrayed the American Black encountering queerness. They commented how the media will perpetuate ideas that Black families are “archaic and monolithic.”

“When I was writing those experiences, that [I] wasn’t painting some picture that was built in the traumatic things that I experienced,” Johnson said. “I wanted to tell the totality of the story how even though my family really loves me [and] really supports me, that there was also things that we got wrong and to be able to share what we got wrong but also how we grew through those things.”

“All Boys Aren’t Blue” is banned in eight states, including Missouri and Florida, in the country due to “profanity, sexually explicit and LGBTQIA+ content.”

Heather Montes-Ireland, assistant professor in Women & Gender Studies, believes that those challenging their book use children as a mechanism.

“I’m thinking about the emotion or impulse behind these book challenges and about the ways the figure of the child is evoked like involuntary childhood innocence,” Montes-Ireland said. “That so many times these book challengers are using rhetoric…to say, ‘we need to protect so and so.’”

Their book is considered Young Adult or YA for ages 12 through 18. They made the decision to write into YA because they wanted to paint the sexual queer experience realistically for Black youth.

“I decided that if I’m going to write for young adults, I’m going to give them the truth about what it felt like, what it was like and how I experienced it, how I processed it, what consent is,” Johnson said. “It all ties back to [the fact] we have no sex education when young adults are becoming adults.”

Johnson was adamant that they write about their queer sexual experience because they believe this age group needs the support the most. “All Boys Aren’t Blue” depicts their encounters with consent and sexual abuse. In 2018, 26 million sexually transmitted infections in the US, and half were from people ages 15-24, according to the CDC.

So when local counties try to ban stories like “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” Johnson said Black youth risk losing another potential resource to learn about sex education.

“Whether they try to ban it or not it has to go out there, and it has to be in the world for that age, because that’s the age who needs it the most,” Johnson said. “That’s what I think about when I’m writing those moments in those moments, thinking about the Black child. The fact that if they don’t read about it here, they may never have another resource that they can get it from. I don’t want them to have to make the same mistakes.”

Challengers have accused the book as being too pornographic. Although book bans are targeting K-3 grade levels, they actually affect K-12 students.

“My book is not for children,” Johnson said. “They use that as a dog whistle word, because every time I go up, it’s a child because it makes you think that some kindergarteners read my book.”

Lauren Roundtree, undergraduate and staff at the LGBTQIA+ Resource Center, recounted how they’ve worked with highschoolers recently, and was surprised how much they know about the world.

“I’m always just really surprised by how much the young people know about the world right now and like about oppression and privilege and they bring up things like fascism and like medical racism,” Roundtree said.

High schoolers and librarians are at the front lines of fighting against book bans nationally. Young activists are fighting to keep books like Johnson accessible.

“I was not aware of any of that when I was in high school,” Roundtree said. “I think a lot about how much power teenagers have for creating.”

Johnson feels inspired by the students who are fighting for books like theirs.

“They want to know more,” they said. “They want to have empathy, they want to know about communities outside defending their rights to have access to materials that they feel not only that they need, but that their classmates need.”

Editor’s note: The original version of this story incorrectly attributed Lauren Roundtree’s quotes to another student. This error has since been corrected in this version.