Chicago Public Schools could see police officers removed from high school campuses as soon as next fall. Last month, Mayor Brandon Johnson announced his support for the Chicago Board of Education’s decision to terminate its $10.3 million contract with the Chicago Police Department. That contract calls for placing uniformed officers in 39 of the city’s public high schools.

During a joint interview with the Chicago Sun-Times and WBEZ, Johnson stated his views on the agreement between Chicago Public Schools and the Chicago Police Department.

“To end that agreement,” Johnson said, “I have no qualms.”

Critics have long argued that stationing officers in educational institutions negatively impacts Black students and students with disabilities. Last year, Illinois Sen. Dick Durbin organized a first-ever hearing on the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

“For many young people, our schools are increasingly a gateway to the criminal justice system,” Durbin told the subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee. “This phenomenon is a consequence of a culture of zero-tolerance that is widespread in our schools and is depriving many children of their fundamental right to an education.”

Rochelle Brewster, a local business owner and grandmother of three students attending Chicago public schools, echoes these concerns, highlighting the deeper systemic issues that contribute to school violence.

“We’re not addressing the root causes,” Brewster said. “It’s not just about having police in schools; it’s about why these kids are getting into trouble in the first place… most lack economic and emotional wellness resources.”

According to the Chicago Tribune, there is no evidence that adding officers for a greater police presence increases safety in schools, adding fuel to the calls for their removal.

This debate gained significant momentum in 2018 surrounding an incident at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, where 17 people were murdered and more than a dozen others were wounded.

Scot Peterson, the armed school resource officer, who was on duty at the school during the time of the shooting was later acquitted of charges for failing to confront the gunman. This sparked nationwide debates over school safety, gun control and the role officers play in schools.

Following recent shootings near Chicago high schools, debates continue to add renewed fears about the safety of students both on and around campus.

Mo Canady, the executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers with over 25 years of experience as an officer, stresses the need for thorough training and that the role of a school officer is not suited for every professional of the field.

“It is perhaps the most unique assignment in law enforcement. It requires individuals who are sincerely committed to the well-being of students,” he said.

Canady believes removing school officers creates a potential risk to school safety.

“Critics often overlook the significant decline in juvenile arrest rates across the country, which have dropped by 74% from 1996 to present,” Canady said. “This isn’t just outside of schools; it’s within them as well.”

Local Chicago School Councils have voted annually on police presence in their schools, leading to a reduction in the number of officers. While 39 high schools still have at least one or two officers, there are no officers assigned to the rest of CPS district-run high schools, according to Chicago Sun-Times and WBEZ.

“The Averted School Violence database contains numerous instances of potential violence that were stopped by school resource officers— incidents that often go unreported. Removing officers risks losing this critical arrest filter and the deep, preventative relationships that officers build with students,” Canady said.

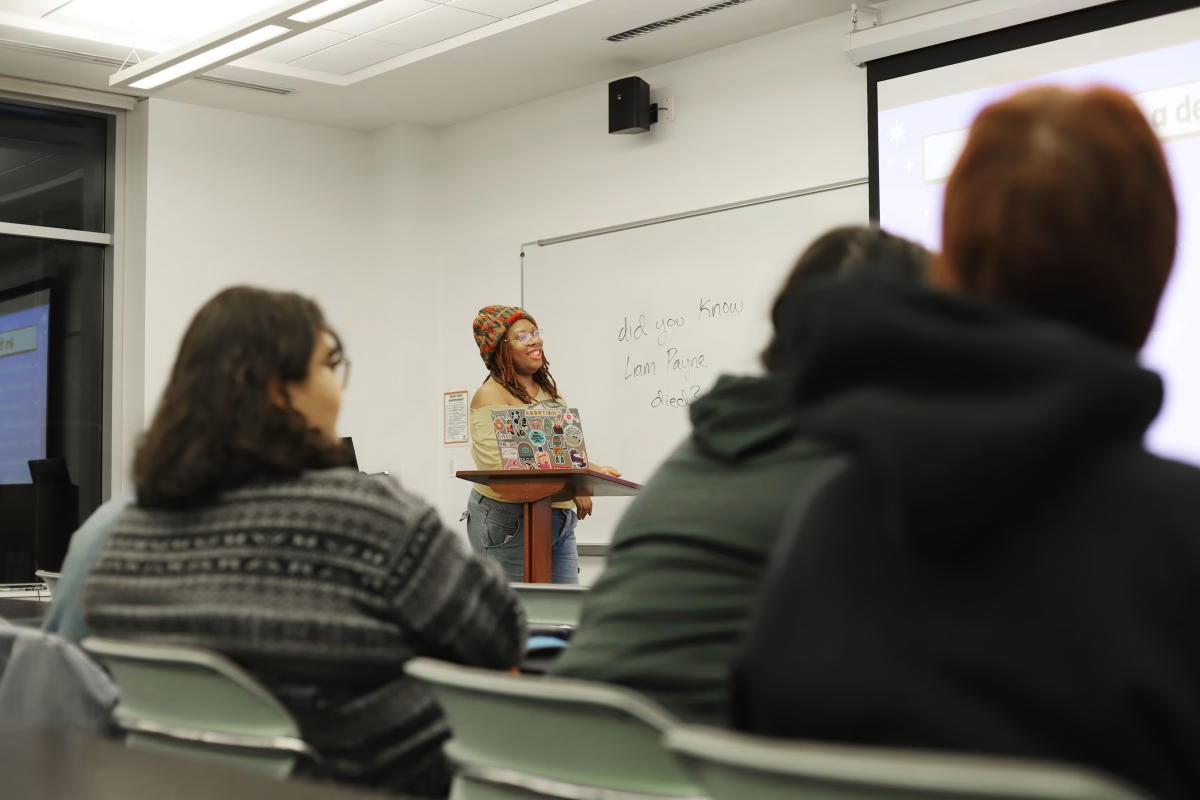

Demetrius, a 15-year-old student and basketball player at a Chicago public high school, shares the officer’s sentiment. Demetrius said the visible presence of officers is reassuring.

“I feel safe when police officers are present at school,” he said. “I know they are there to make sure we aren’t being bullied.”

Demetrius recalls a tense encounter, highlighting the uncomfortable nature of school rivalries.

“I’m a freshman and I didn’t even know who my enemies were. Suddenly, students showed up, looking to start trouble with some of us and the police were there to stop it,” he said.

Alternative safety plans have gained momentum, with some schools using additional funding to explore alternatives to police-based discipline. Social-emotional learning and restorative justice initiatives, including peer-to-peer intervention at some high schools, are aimed at reducing conflict before it escalates.

Brewster is among those who think money spent on placing officers in schools should be used differently.

“That money could make a difference if we put it into educational resources, mental health support and after-school programs,” she said. “We need to address the real issues behind student behavior and make our schools safer as a community.”