In her 2011 article, “The Iraqi novelist on the second floor,” former Chicago Tribune columnist Mary Schmich described Mahmoud Saeed’s apartment as having “just enough space” for his essentials with his desk positioned by the window, overlooking Belmont Avenue.

That was where he preferred to write — looking through the trees and down toward Clark Street.

Saeed, an acclaimed Iraqi novelist and former DePaul professor, held orange prayer beads in hand during his interview with Schmich. Scattered around him were books, some in Arabic and some in English. Friend and transcript translator, Allen Salter, sat at his side. Schmich wrote:

“I like Americans very much,” (Saeed) says. “I like Clark Street very much. Friday, Saturday night, it is very vivid?”

He looks toward his friend Allen Salter. “Lively,” says Salter.

Salter first met Saeed at the turn of the century. A friend had emailed him about an Iraqi novelist who was looking for someone that could translate his writing from Arabic to English.

Back in Iraq, Saeed was no stranger to censorship. Authorities had banned publication of his novels from 1963 to 2008. He was arrested and imprisoned six times under Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist regime. To escape persecution, Saeed and his family immigrated to the United Arab Emirates, then back to Iraq and landed in Dubai.

Saeed immigrated to Chicago in 1999. He dreamt of finding success as a novelist in the United States. His family was left behind in the Middle East.

Throughout the years, Salter and Saeed sat side by side many times. They would review transcripts, drink coffee, discuss politics, tell jokes and laugh together.

It has been almost 14 years since Salter sat beside Saeed during that interview. And, on Jan. 20, 2025, Salter sat beside Saeed yet again as he drove him from O’Hare International Airport to Illinois Masonic Medical Center’s emergency room.

The car ride was mostly silent, with the exception of Saeed mumbling to Salter. “I’m really happy to be back in Chicago. I love Chicago,” Salter remembers his friend saying.

A week later, at age 89, Saeed died in the hospital with the friend he called his “American daughter,” Jackie Spinner, beside him.

Saeed was a man who fled his country out of necessity — a man who had to fight every step of the way to advocate for his writing at the sacrifice of his family. Spinner provided him a second chance to be a father, grandfather and writer.

Back in 2011, Spinner had just finished her work as a Fulbright Scholar in Oman where she covered the Arab Spring as a freelance journalist.

She was struggling with the idea of living in the United States once again. But, she had to come home to Chicago. The first of her three adopted sons from Morocco would soon arrive. Her village — her primary support system — was here.

To calm her restlessness, Spinner looked for ways to connect with what she missed most about Iraq. In the process, she stumbled upon the story about Saeed in the Tribune.

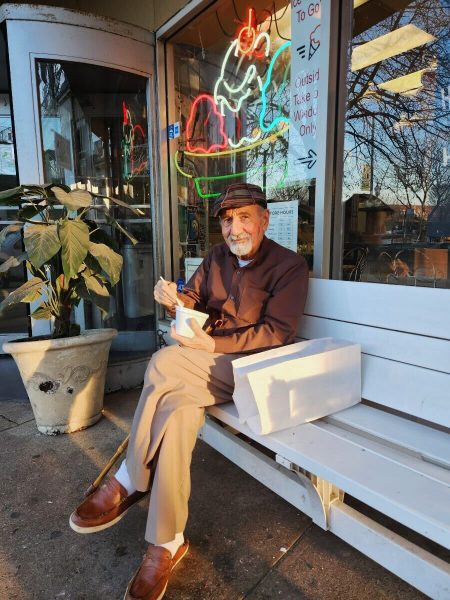

Photo provided by Maryann Michael

“I was fascinated,” said Spinner, now a journalism professor at Columbia College Chicago. “I knew I had to meet him.”

The two first met at a Starbucks in the Wrigleyville neighborhood. During the following years, Spinner and Saeed continued to meet, almost weekly, at that very same spot.

“We spoke in Arabic. … He corrected my Arabic,” Spinner said with a chuckle. “He told me these fabulous stories about Iraq and Iraqi history and Arab history and novels and literature and politics. It was in that Starbucks that he became my mentor and teacher.”

It wasn’t until her first son arrived from Morocco, Spinner said, that Saeed really became part of her family.

“My dad died when I was younger,” Spinner said. “Mahmoud became my son’s grandfather and, by extension, I became his American daughter.”

Often, Spinner would come home from work and find Saeed cooking as he held one of her sons at his hip.

Saeed let himself in through the back door whenever he pleased. He would play with the kids. He would give Spinner unsolicited parenting advice. And he was almost always there to celebrate holidays with the family.

Spinner taught her sons to call Saeed “jiddo,” meaning “grandfather” in Arabic.

In 2016, Spinner, Saeed and her sons were at the Lincoln Park Zoo admiring the holiday lights. Saeed was pushing the stroller when he collapsed.

“I got him up,” Spinner said. “I got him in the car. I got the kids in the car. That’s when he told me he had leukemia.”

He was facing his mortality, Spinner said. Only once Saeed expressed to Spinner that his “bucket-list wish” was to write a novel from Iraq.

Saeed had not been back to write since he had been exiled years ago. Instead, he traveled to India, Mexico and other countries around the world. He wanted to find reminders of the sounds, smells, landscapes and people of Iraq. They helped him write. They reminded him of the home he missed so much.

Saeed initially responded to treatment, and his cancer was in remission. With the brief upturn in his health, Spinner knew she had to find a way for Saeed to write in Iraq once more.

Spinner had worked at the American University in Iraq and, through her connections, got Saeed a position as the university’s first writer-in-residence. She wanted a new generation to know his stories and learn about what happened to him under the Ba’ath regime.

She also wanted him to have the gift of returning to write and, perhaps, complete one last novel.

After his academic appointment ended, Saeed returned to Chicago and began to get sicker. His cancer had returned and the side effects he was experiencing from treatment were not worth the possibility of survival.

In 2023, with his daughter on the phone and Jackie sitting beside him, the decision was made to end his treatment. The plan was for Saeed to live out his days with his daughter in Dubai.

During the appointment, Saeed motioned to Spinner, silently, asking for her notepad. He scribbled something in Arabic. Salter later translated it for Spinner.

He had written, “Enough with this bulls— talking.”

“He just wanted to live,” Spinner said. “When somebody robs you of your freedom, you spend the rest of your life protecting that freedom.”

Saeed boarded a plane to Dubai with three months worth of medication. He was expected to live that long, if not weeks, before his kidneys would fail.

Spinner and Salter did not expect to see him again.

Ten months later, Saeed sent Salter an email asking for a case of Heineken, some peanut butter and aspirin, “because he had a terrible headache.” Confused and concerned, Salter contacted Saeed’s daughter who told him that she just put him on a plane back to the United States.

Saeed had told his daughter that there was something wrong with his heart — something that could only be fixed in Chicago.

Salter hurried to the airport to try to meet his old friend. An attendant pushed Saeed out of the exit in a wheelchair.

“What are you doing here?” Salter asked Saeed, horrified. “What’s your plan? What are you going to do? You don’t have anywhere to go!”

Saeed, looking into Salter’s eyes, responded simply: “What are you doing here? You weren’t supposed to know I was coming.”

Days before, Saeed had made his daughter promise not to tell anyone of his return. His plan was to take a taxi to the hospital alone. He thought he would be taken care of and spend his final days there.

“I’m really glad she broke a promise,” Salter quietly said, thinking back to that call.

Provided by: Maryann Michael

Salter and Spinner alternated their time visiting Saeed in the hospital. Saeed’s former student from DePaul, Maryann Michael, was also called and informed of his condition.

Michael fondly remembers her time with Saeed years ago. When they first met, he was teaching an Arabic calligraphy course at DePaul. Saeed would glance over her shoulder as she meticulously drew each character and would mutter to her, “slow like the ant, … slow down, slow down, focus on the form of the art.”

One afternoon, Saeed found her on the “smoking steps” outside of the Levan Center. He asked to grab a coffee.

Since that first coffee, Michael and Saeed have met once a month almost every month during his time in the States. The two would chat about the weather, the things Saeed was writing and Michael’s cat, Kabeer. Saeed had always liked that Michael had named her cat something in Arabic.

Saeed became a grandfather to Michael and, in the days before his death, she would visit and read him poetry while holding his hand.

“I always appreciated his friendship,” Michael said. “It wasn’t until I was a lot older that I realized how valuable he was to me, how deep my love and care developed for him over the 15 years of knowing him. My connection with him helped me realize how precious life is — how precious our time together was and how very lucky and very blessed I am to have known him.”

Over the course of his career, Saeed produced more than 20 novels and short stories. Three of his novels — “Saddam City,” “Two Lost Souls” and “The World Through the Eyes of Angels” — have been published in both English and Arabic.

Aside from a few smaller awards and newspaper articles, Salter said that Saeed never found the fame he had hoped for when he moved to the United States.

“He lived the life of the starving artist, you know, not literally, but never made a lot of money from it,” Salter said. “He was a hard-working professional, and he kept writing, kept producing.”

Spinner’s sons called their jiddo to speak to him by phone. Her eldest son, now 13, came in person to say goodbye.

In Saeed’s final hours, Spinner whispered to him, “I’m not going to let them forget you.”

“He feared death because he didn’t want to be erased like Hussein’s regime had tried to erase him in Iraq,” she said. “He came to America to be remembered.”

Now Spinner finds herself trying to figure out how to buy his headstone.

“I don’t want him in an unmarked grave,” she said. “I want his name there, ‘Mahmoud Saeed: father, grandfather, writer.’”

“I want to give him what I promised him I would … to be remembered.”

Related Stories:

- From struggle to sanctuary: Seth Botts’ journey of redemption, faith, and radical love

- The sounds and sights of live band karaoke at Bub City with Alexander Lehr

- Music is the medicine: Families remember gun violence victims with songs

Stay informed with The DePaulia’s top stories, delivered to your inbox every Monday.